Nutrition and diabetic retinopathy: a path to sight-saving changes

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of vision loss for the working-age population, which is only expected to rise with increasing diabetic prevalence worldwide, the ageing population and increasing life expectancy. It is well known that nutrition and caloric intake play a pivotal role in mitigating the complications of diabetes, including retinopathy.

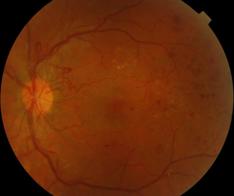

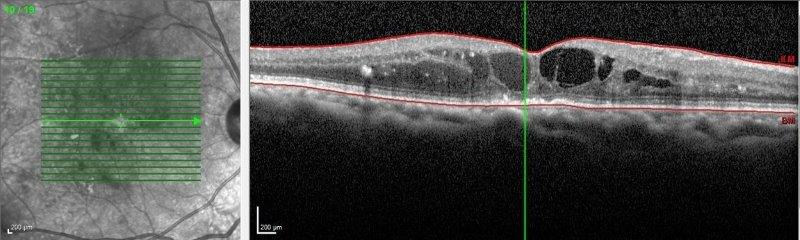

DR is classified as either non-proliferative (NPDR) or proliferative (PDR) (Fig 1). In NPDR we observe signs of retinal vessel damage and leakage, with microaneurysm formation, haemorrhage, exudation and venous beading. New vessel formation (neovascularisation) is the hallmark of PDR, which occurs in more severe disease and is associated with vision-threatening complications including vitreous haemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment1. Diabetic macular oedema (DMO) is the leading cause of visual impairment, occurring at any stage of DR (Fig 2). DMO is characterised by fluid accumulation at the macula due to breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and increased vascular permeability, led by signalling mediators, primarily anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF).

New Zealand photo-screening data confirms type 1 diabetics (T1DM) are more likely to develop more severe DR/DMO and be referred to ophthalmology. Referrable DR (severe NPDR and PDR) accounted for 4.4% of T1DM and 1.6% of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) patients seen at screening. Referrable maculopathy occurred in 4.8% and 2.8% of T1DM and T2DM patients, respectively. An ethnic preponderance exists, such that Māori, Pacific peoples and Indian ethnicity have more severe disease2.

Glycaemic (blood sugar) control and duration of diabetes are the main risk factors for DR development, with hypertension and elevated lipids being well known risk factors which are modifiable with diet. As preventing vision loss is a powerful motivator for diabetic control, the authors believe eyecare professionals have a role in providing patients with evidence-based nutrition and dietary advice that may be sight-saving as well as critical to mitigating systemic complications of diabetes.

Fig 1a. Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Fig 1b. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy of the disc/retina (see main pic for Fig 1c)

Dietary patterns

The New Zealand health guidelines promote a variety of nutritious food with plenty of vegetables and fruits, grains (whole grain and naturally high in fibre), some milk (ideally low fat), legumes, nuts/seeds, fish/seafood, eggs, poultry and/or red meat (with extraneous fat removed). This includes choosing foods that are whole, avoiding processed foods (high in refined grains, saturated fats, sugar and salt) and making plain water your first drink of choice3.

Remission for T2DM patients is considered a treatment goal. The main driver appears to be weight loss, best demonstrated through the DiRECT trial, using calorie-restricted diets coupled with lifestyle changes. Clinically significant weight loss is 5%, with remission rates proportional to the amount of weight loss4. Moreover, for DR patients, the harmful effects of a high-calorie diet have been demonstrated. There is also evidence supporting a protective effect from a 'Mediterranean diet', although there is limited evidence when assessing its impact on DR. Overall, the Mediterranean-style, low-fat, or low-carbohydrate eating pattern is supported by the American Diabetes Association as having the best evidence for the prevention and management of T2DM5.

High levels of vegetables and fruits are also protective against DR, as well as being good sources of dietary fibre with a low glycaemic index, helping to better manage the blood sugar response following mealtimes6.

Fig 2. Ocular coherence tomography of DMO

Glycaemic control

Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) protein levels are the gold standard measure of glycaemic control, providing a snapshot over the preceding 2-3 month period.

Two landmark trials, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) highlighted the benefits of tight glycaemic control (using HbA1c) in reducing the incidence and progression of DR in T1DM and T2DM patients, respectively. Epidemiology of Diabetic Interventions and Complications (EDIC), a follow-up study to DCCT, demonstrated the benefits of tight glycaemic control continued through 10 years – a phenomenon known as ‘metabolic memory’. Clinicians and patients should also be aware that rapid blood-sugar control may lead to a paradoxical short-term worsening of retinopathy following the normalisation of blood sugars, which should be watched closely. More recently, glycaemic variability, referring to fluctuations of blood glucose over the day, has been found to be a predictor of DR7.

Given the significance of diabetic control, early identification of poor control is critical. In a New Zealand setting, HbA1c level greater than 75mmol/mol (or HbA1c >9%) is a significant predictor of vision-threatening retinopathy or maculopathy2.

Dietary advice

Choose low glycaemic index (low-calorie) foods, especially non-starchy vegetables, and grain food high in dietary fibres (brown/basmati rice, whole-grain bread and porridge) instead of refined grains (white rice, white bread and many breakfast cereals). Eat fresh fruit and drink plain drinking water, instead of sugary drinks, and choose whole foods over processed foods as much as possible5,8.

Soft drinks

It’s well-accepted that sugar-sweetened beverages (soft drinks) and sugar-free (diet) carbonated beverages are associated with high HbA1c and poorer cardiovascular outcomes. The direct link with DR (and other microvascular complications) needs further interrogation, with only a few observational studies suggesting an association and only for diet soft drinks6.

Fats

Hyperlipidaemia is a risk factor for DR progression, particularly DMO, although the mechanism is unclear. A 2015 meta-analysis (n=17,907) confirmed a relationship between dyslipidaemia (elevated total cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides) and DMO9. The benefit of the main vasoprotective lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), is unclear from the 2015 meta-analysis, although a more recent systematic review found HDL to have an overall protective effect10. The ability of the Mediterranean diet (enriched with virgin olive oil) has been shown to positively modify HDL.

There are three kinds of naturally occurring fatty acids – saturated (SAFA), mono-unsaturated (MUFA) and poly-unsaturated (PUFA), see Table 1.

Table 1: Common sources of natural fats

|

Products |

Association |

|

|

Saturated fatty acids (SAFA) |

Dairy (milk, cream, butter, cheese), fatty cuts of meat, palm/coconut oil, cakes, pastries, biscuits |

Increase LDL (bad) cholesterol |

|

Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) |

Olive, canola, peanut oils; avocado, almonds, hazelnuts, peanuts, macadamia nuts |

Increase HDL (good) cholesterol |

|

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) |

Omega-6: seed oils (sunflower, safflower, soybean, corn), walnuts Omega-3: oily fish, green leafy vegetables |

Lower LDL (bad) cholesterol |

|

Trans fats |

Margarines, confectionery fat, ‘fast food’ |

Harmful |

Both MUFA and PUFA have protective benefits when considering associations with DR. Oleic acid (representing 90% of MUFAs) is the main fatty acid in olive oil, seen as protective against DR and an important component of the Mediterranean diet. The strongest evidence for PUFAs has been found in the omega-3 form, best sourced from oily fish. In a subanalysis of patients on the Mediterranean diet from the landmark Prevention with Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) trial, intake of at least 500mg/day of omega-3 PUFAs (achieved by at least two weekly servings of fish) can reduce the risk of sight-threatening DR by almost 50%11.

Dietary advice

One handful (30g) of nuts/seeds daily, 1-2 servings of fish weekly and low-fat milk replacement8.

Salt intake

There is strong evidence that reducing blood pressure lowers the risk of DR and its progression, especially in T2DM with severe hypertension. This was highlighted in the landmark UKPDS trial, reporting a 50% reduction in vision loss (3 lines ETDRS chart) in patients with systolic blood pressure (SBP) <150mmHg, compared to those with <180mmHg12. Evidence shows reducing the average sodium intake can reduce the population’s blood pressure. Sodium is consumed largely as salt, with 2,000mg equivalent to roughly one teaspoon of salt. A modest reduction in salt intake by three-quarters of a teaspoon of salt has been shown to reduce SBP by 5mmHg13. Observational evidence indicates that high sodium intake was linked with a higher incidence of DR as well as being a predictor of DMO6.

The current average sodium intake in New Zealand is 3,600mg/day (almost double the recommended guideline), mostly from cereals and processed meat. Choosing ‘whole’ or less processed foods low in salt (such as vegetables, fruit, fish and poultry) and low-salt seasoning (herbs, spices, citrus) when enhancing flavours is recommended. Reducing the salt in high-salt foods (such as corned beef) can be achieved by changing the water two or three times while cooking3.

Dietary advice

Limit high-salt foods, use minimal salt in cooking and limit high-salt seasoning to once daily.8

Antioxidant supplementation

The association of specific antioxidants (carotenoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, riboflavin and selenium) with DR is mainly observational in nature and limited6. A systematic review was unable to find an association for vitamins C, D or E, and riboflavin. A few isolated studies reported a protective effect for selenium and vitamin B6 – an association needing further investigation6.

While the role of oral antioxidant supplementation has proven beneficial in other retinal conditions (ie. AREDS-2 supplement for age-related macular degeneration), there is no evidence to support routine oral supplementation for diabetic patients or patients with DR5,6.

Conclusion

Optimising diet is a recommended strategy for helping treat and prevent the progression of DR. A balanced eating pattern including fibre-rich foods, vegetables and whole grains, while avoiding processed foods, high salt intake and sugary beverages, will benefit glycaemic management and retinopathy progression. Most individuals with T2DM benefit from weight loss. Incorporating monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, such as olive oil, almonds and omega-3 fatty acids found in fish and vegetables, can also provide further benefits. Thus, clinicians can help guide patients to optimise their nutrition to lower their risk of vision-threatening complications associated with DR.

References

1. Wang W, Lo A. Diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiology and treatments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018; 19: 1816.

2. Hill S, Mullins P, Murphy R et al. Risk factors for progression to referable diabetic eye disease in people with diabetes mellitus in Auckland, New Zealand: a 12-year retrospective cohort analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 2021; 10: 579-589.

3. Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults. In. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2020.

4. Lean M, Leslie W, Barnes A et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet 2018; 391: 541-551.

5. Evert A, Dennison M, Gardner C et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 731-754.

6. Shah J, Cheong Z, Tan B et al. Dietary intake and diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review of the literature. Nutrients 2022; 14: 5021.

7. Sun B, Luo Z, Zhou J. Comprehensive elaboration of glycemic variability in diabetic macrovascular and microvascular complications. Cardiovascular Diabetology 2021; 20.

8. Ministry of Health. Guidance and Management of Type 2 Diabetes. In: Ministry of Health, 2011.

9. Das R, Kerr R, Chakravarthy U et al. Dyslipidemia and diabetic macular edema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2015; 122: 1820-1827.

10. Soedarman S, Kurnia K, Prasetya A et al. Cholesterols, apolipoproteins, and their associations with the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. Vision 2022; 6: 77.

11. Sala-Vila A, Díaz-López A, Valls-Pedret C et al. Dietary Marine ω-3 Fatty Acids and Incident Sight-Threatening Retinopathy in Middle-Aged and Older Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmology 2016; 134: 1142.

12. Group UPDS. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998; 317: 703-713.

13. He F, Li J, Macgregor G. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013; 346: f1325-f1325.

Dr Dan Scott is an ophthalmology junior clinical research fellow at the University of Auckland, supervised by Drs Niederer and Sophie Hill. His research focus is the clinical presentation, treatment and outcomes for patients with diabetic retinopathy. Dr Scott has experience as a non-vocational ophthalmology registrar in both Gisborne and Hamilton, as well as a neuro-ophthalmology junior clinical research fellow in Auckland.

Dr Hannah Ng is an ophthalmology junior clinical research fellow at the University of Auckland, supervised by Dr Niederer. Her research focus is streamlining intravitreal services in Aotearoa. Her recent clinical experience includes a non-vocational ophthalmology registrar year in Auckland.

Dr Rachael Niederer is an ophthalmologist specialising in uveitis and medical retina, working at Greenlane Clinical Centre and Auckland Eye, and a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland. She has a special interest in diabetic eye disease and ocular inflammation.