Case study: Transient smartphone blindness

A 52-year-old female presented to the hospital medical assessment unit due to several episodes of right-eye blindness lasting 10-15 seconds over a few months. These episodes occurred only at night before sleeping and were noticeable when she covered her left eye. Several blood investigations for underlying autoimmune disorders or prothrombotic risk factors returned normal. A head CT scan with an angiogram of carotid and intracranial arteries were normal. She was started on antiplatelet medications (clopidogrel and aspirin) with a possible diagnosis of amaurosis fugax and was prohibited from driving for three months.

An urgent review with a neurologist in stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA) clinic was sought. TIA was considered unlikely and a presumptive diagnosis of visual phenomenon related to migraine was suspected. She was started on migraine prophylaxis. An MRI of the brain and orbits with contrast was found to be normal. A referral to the neuro-ophthalmology clinic was made. She continued to have symptoms despite dual antiplatelets. However, when she started experiencing post-menopausal bleeding with dual anti-platelets; aspirin was stopped, while clopidogrel was continued.

History solves the mystery

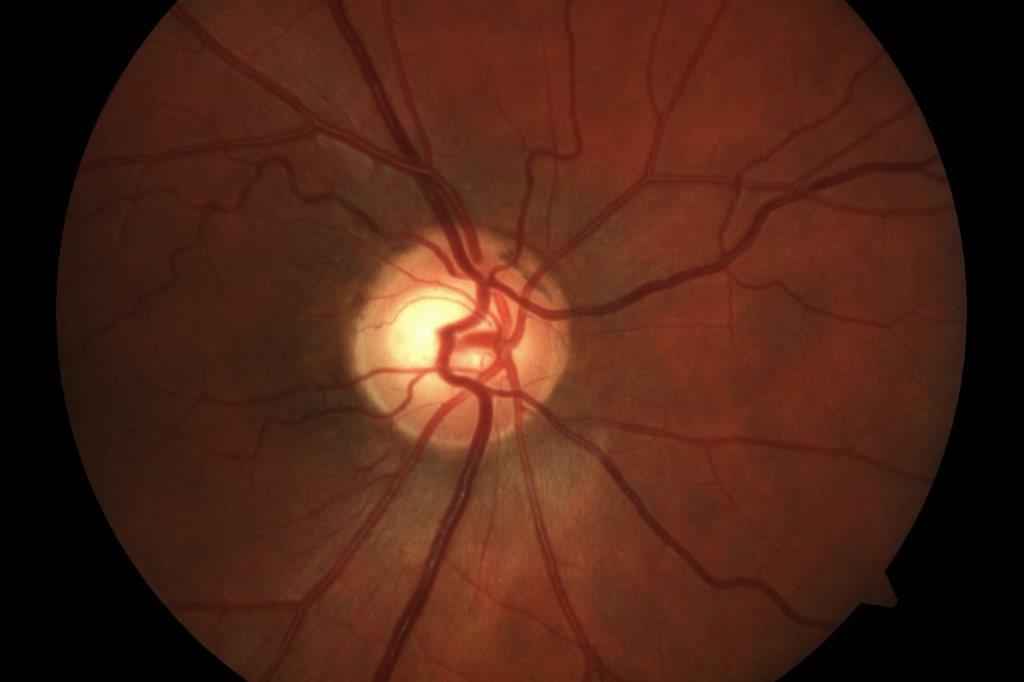

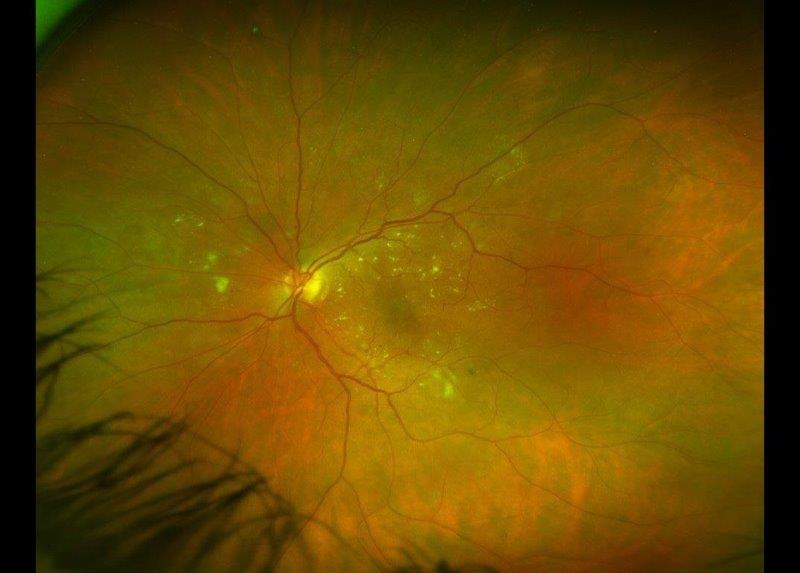

At the neuro-ophthalmology clinic, the patient’s history was revisited. She continued to have two to three episodes of transient blindness every week, similar to the frequency prior to starting anti-platelets. These episodes occurred only in the right eye after staring at the bright screen of the smartphone for 30 minutes while lying on the left side in a dark room. All the episodes happened soon after turning off the smartphone and lasted for 10-15 seconds, following which the vision slowly recovered. The ocular examination was normal, including visual fields, retinal nerve fibre layer and ganglion cell layer scans.

A diagnosis of transient smartphone blindness (TSB) was made. Clopidogrel and migraine prophylaxis were discontinued. The association between smartphone use in the dark and episodes of transient blindness was explained to her and she was advised to cease phone use in a dark room before bedtime. She was unhappy and reluctant to accept the diagnosis.

At a four-month telephone follow-up, she had not experienced any further episodes since the first consultation, even though she continued not to accept the diagnosis of TSB.

Discussion

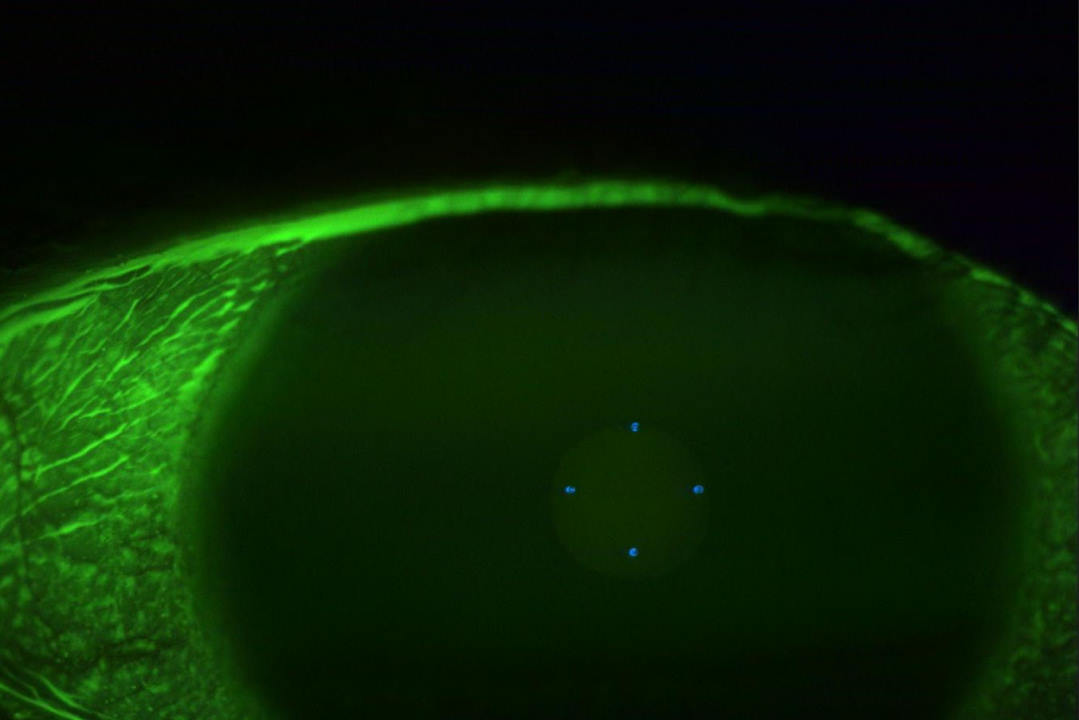

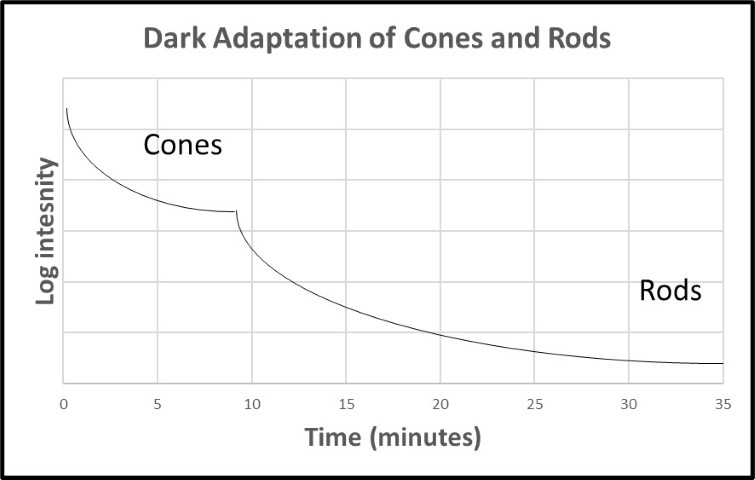

Photoreceptor sensitivity increases slowly on moving from a light to a dark room to enable us to see in the dark. The dark-adapted photoreceptors are more sensitive to dim light (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Dark adaptation of cones and rods over time with prior light adaptation

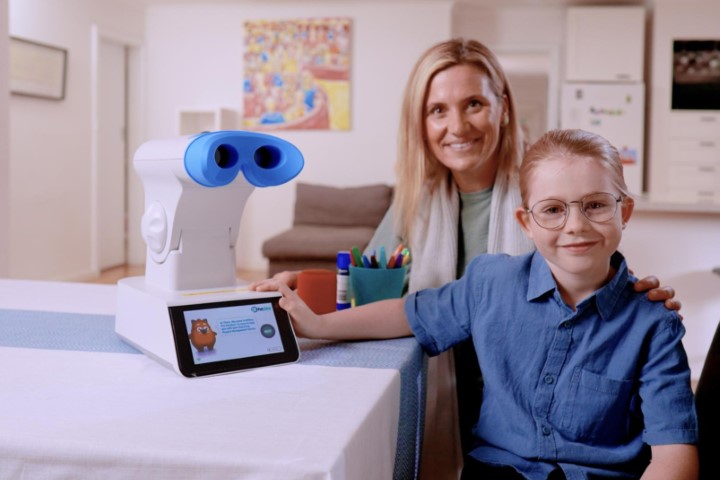

Viewing a bright screen in a dark room causes the eye to be light-adapted. Monocular TSB occurs when one eye views a bright screen in a dark room, causing it to be light-adapted, while the other eye is obscured, causing it to be dark-adapted. This typically happens when lying down on one side and the dependent eye is obscured by the edge of the pillow (Fig 2, top)1. The dark-adapted eye is more sensitive in the mesopic/scotopic setting, while the light-adapted eye has been bleached by the smartphone, reducing its sensitivity and requiring more time to adapt to the darkness again2. Hence, the sensation of transient blindness in the light-adapted eye on turning off the smartphone.

It is common to misdiagnose TSB as thromboembolic aetiology, which can lead to unnecessary treatment with anticoagulants3. A clear and precise history is required, along with a physical examination of the eye in any case of vision loss. The exact duration and events leading up to the vision loss are key to correct diagnosis. However, in many cases TSB is a diagnosis of exclusion and a confirmed diagnosis can be established in retrospect, ie. after complete resolution of symptoms on ceasing smartphone use in a dark room, plus investigations to rule out more sinister causes.

Bright screens (especially smartphones) disrupt sleep cycles in our circadian rhythm due to blue light emittance. The normal circadian rhythm involves melatonin production after sunset to enable sleepiness4. This occurs due to less blue light at sunset as sunlight enters the atmosphere at a different angle, resulting in differential absorption and scattering of light compared to daytime. Blue-light exposure at night causes reduction of melatonin, causing the brain to think it’s daytime4.

It is advised that screens should not be used in the hours leading to bedtime. Most computer screens are compatible with software (such as f.lux) which reduce blue-light emittance at set times. Many newer smartphones have software which also does this.

Differential diagnoses for unilateral transient vision loss without other symptoms

- Thromboembolic disease, such as amaurosis fugax

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Giant cell arteritis/arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

- Optic neuritis (and/or multiple sclerosis)1

Management advice

- Reduce smartphone usage in dark or night-time, especially one to two hours before bedtime, to aid sleep4,5

- Establish a night-time routine, which may involve the bedroom being a screen-free zone and dimming of bedroom lights5

- If using smartphone at night, use in a position in which light enters both eyes6

- Enable blue-light-reducing software (such as night-time mode or the Twilight app) to reduce the effects on the sleep cycle if cessation is not possible

Key points

- A precise history of exact timing and events related to blindness are key to identifying and ruling out certain differential diagnoses

- Smartphone usage is clearly on the rise, especially in younger generations6, therefore this phenomenon is becoming more common

- Reducing screen use one to two hours prior to sleep can aid in a healthier sleep cycle

- Sometimes TSB is a diagnosis of exclusion after ruling out more sinister causes. It might also be made retrospectively, if symptoms cease following cessation of phone use in the dark.

References

- Winters J, Bhagat N. Transient Smartphone Blindness 2021. Available from https://eyewiki.aao.org/Transient_Smartphone_Blindness

- Alim-Marvasti A, Bi W, Mahroo O, Barbur J, Plant G. Transient smartphone “blindness”. NEJM. 2016;374(25):2502-4

- Sathiamoorthi S, Wingerchuk D. Transient smartphone blindness: relevance to misdiagnosis in neurologic practice. Neurology. 2017;88(8):809-10

- National Sleep Foundation. Screen use disrupts precious sleep time 2022. Available from https://www.thensf.org/screen-use-disrupts-precious-sleep-time/

- Sleep Foundation. How electronics affect sleep 2023. Available from https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/how-electronics-affect-sleep

- Hasan C, Hasan F, Shah S, Hasan C. Transient smartphone blindness: precaution needed. Cureus. 2017;9(10).

Dr Arvind Gupta is a consultant ophthalmologist specialising in cataract, medical retina and neuro-ophthalmology. He is based at Manukau Super Clinic, Greenlane Clinical Centre and Eye Doctors in Auckland.

Kenny Wu is a therapeutic optometrist at Eye Institute and Te Whatu Ora Counties Manukau. He has a clinical background in ocular surface disease and medical retina.