Unravelling the mystery of corneal peripheral thinning disorders

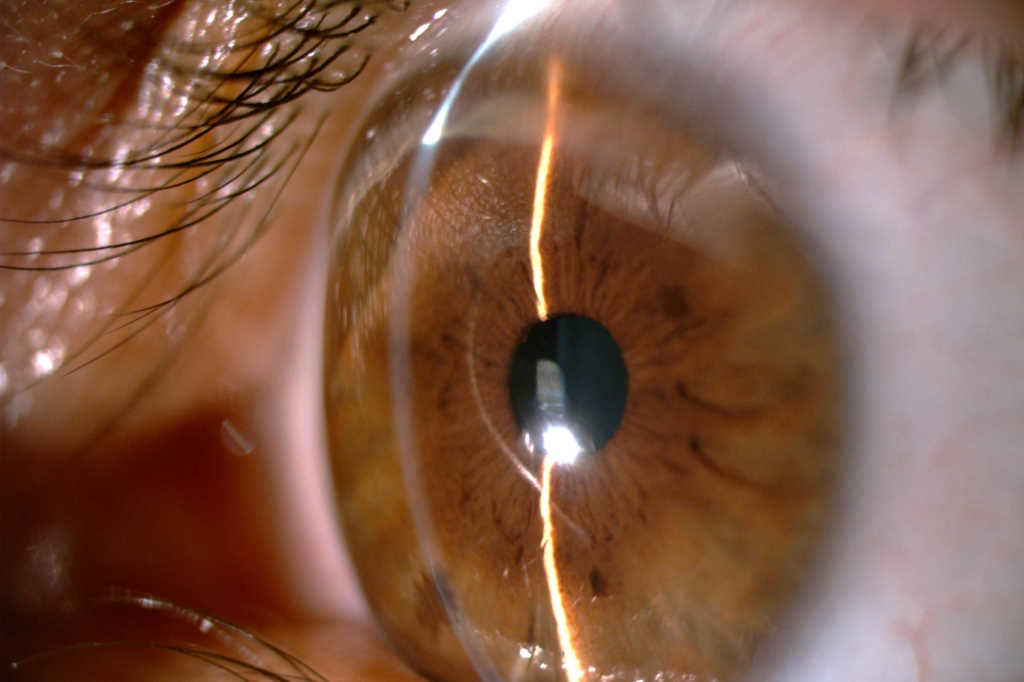

The anatomy of the peripheral cornea and its proximity to the vascular limbus makes it prone to a unique set of diseases, primarily immune-mediated ones. However, the limbus is still prone to infectious and degenerative diseases and thus distinguishing diseases may be difficult, so a diagnosis is often made by a process of elimination.

In particular, thinning disorders of the peripheral cornea always pose a diagnostic dilemma to eyecare professionals. As a first step it is important to take a detailed history of any previous episodes and autoimmune diseases. In the examination, it is important to note whether the thinning occurs in the context of a red or a quiet eye. Moreover, the morphology of the thinning and the associated findings are important in making the correct diagnosis. This article discusses the clinical profiles of some common peripheral thinning disorders

Peripheral thinning disorder in the ‘white’ eye

Dellen

Dellen is a discrete area of corneal thinning caused by dehydration. It occurs adjacent to an area of elevation, often a pterygium or scar. As a result of the elevation, tears do not distribute uniformly, leading to dryness in some areas and subsequent thinning. Simple lubrication or treatment of the elevated area normally stops further thinning.

Terrien’s marginal degeneration

Terrien’s marginal degeneration is an idiopathic corneal thinning condition. It starts superiorly initially as an opacity with a lucid interval between it and the limbus (Fig 1). The thinning progresses gradually in a circumferential manner, with vessels growing over the thinned area from the limbus. The vessels leak lipids at the leading edge of the thinning. This condition is seen in white eyes and is non-painful with an intact epithelium. Typically, both eyes are involved to different degrees. Vision fluctuates secondary to astigmatism as the disease progresses. Unfortunately, there is no cure for this disease.

Senile furrow

Senile furrow affects the elderly where there is thinning or an illusion of thinning in the peripheral cornea, often in the lucid area separating the limbus from the corneal arcus. It’s benign and requires no treatment.

Pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD)

PMD is an ectatic disease of the cornea where the thinning is typically inferior and peripheral in the cornea. The protrusion in the cornea is superior to the area of thinning, giving a ‘beer belly’ shape (Fig 2). This is in contrast to keratoconus, where the protrusion is at the site of thinning. On the other hand, keratoglobus is a condition where the whole cornea is uniformly thin. PMD is bilateral and is often seen in older patients (20-40 years) than keratoconus. The peripheral cornea is clear (hence, ‘pellucid’). The topography may show pronounced against-the-rule astigmatism or a claw-crab pattern.

Peripheral thinning disorders in the ‘red’ eye

Eyes with peripheral thinning and redness should always trigger a differential diagnosis of infectious keratitis (Fig 3). Such eyes often exhibit hypopyon. Risk factors include contact lens wear, trauma and use of topical steroids. Nevertheless, there are other thinning disorders where the diagnosis is especially important to make, since they can be life threatening.

Marginal keratitis

Marginal keratitis is a staphylococcal type III hypersensitivity (immune-complex) reaction which occurs secondary to the exotoxins released by staphylococcal bacteria in the lids. Typically, infiltrates with-or-without thinning occur 1mm central to the limbus with a clear zone in between. They occur at 2, 10, 4 and 8 o’clock positions where the eyelid is in contact with the eyeball. It is important to exclude infectious keratitis. However, such infiltrates normally have an intact epithelium and respond well to low potency topical steroids. The blepharitis should be treated with warm eyelid compresses, Fucithalmic (fusidic acid) eye ointment and oral doxycycline/azithromycin.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK)

PUK describes ulceration in the peripheral cornea usually in the absence of an infiltrate. PUK is caused by an immune-complex related melt, usually associated with life-threatening vasculitides such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In such disease, immune complexes activate the complement system, which attracts immune cells and leads to massive release of proteases resulting in collagenolysis. Adjacent scleritis is usually a feature of this disease (Fig 4). Pain, photophobia and redness are common symptoms. Specifically, rheumatoid arthritis can lead to scleral/corneal collagenolysis without any associated inflammation, also known as scleromalacia perforans (Fig 5).

Mooren’s ulcer

Mooren’s ulcer is PUK without any associated immune disease. Effectively, it is a diagnosis of exclusion. The disease can be unilateral, occurring more in older people (type I), or bilateral, occurring in younger patients usually of an African descent (type II). The disease is very painful and has no associated scleritis. Earlier observations suggested an association with chronic hepatitis C. However, this remains unproven. Type I disease usually responds well to medical and surgical treatment. However, type II is usually more severe and the prognosis is poor. Mooren’s ulcer starts as a crescent-shaped thinning in the periphery, usually nasal/temporal, then progresses circumferentially. The leading edge has an overhang or undermined edge. The melt in Mooren’s ulcer is often severe and is extremely prone to perforation with minor trauma such as eye rubbing.

Management

All thinning disorders in the context of a red eye should be investigated for underlying infection or rheumatological disease. Hypopyon is an important sign of infectious keratitis. Investigation for PUK includes full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein (CRP), anti-nuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, syphilis serology and QuantiFERON-TB gold (to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis).

The management of non-infectious PUK includes treating the underlying disease and halting further melting. Preservative-free lubricants and prophylactic topical antibiotics are used in most cases. In the context of marked thinning, topical steroids should be avoided or used cautiously. In contrast, systemic steroids are the mainstay induction agents for immunosuppression. However, starting steroid-sparing immunomodulators such as mycophenolate, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, rituximab and anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents early in the course of the disease leads to favourable prognosis, especially mortality.

An Auckland study found the survival rate for those with PUK/necrotising scleritis is 24.7 years and 10.7 years for those who received immunomodulatory therapy and those who did not, respectively1.

Surgical treatment of PUK may include conjunctival recession/resection. This prevents the immune cells/complexes from reaching the corneal limbus and thus less enzymic tissue destruction. Perforations in the context of PUK are difficult to treat and have very poor prognosis, especially if a tectonic graft is needed. It is very important to control the underlying inflammation prior to surgery for a graft to survive.

Conclusion

Corneal peripheral thinning is a common encounter in ophthalmology and less so in optometric practice. There are several degenerative conditions which cause thinning without any associated inflammation. However, in the context of a red eye, it’s important initially to exclude an infectious cause. Any underlying rheumatological disease should be investigated and treated. In the long-term, immunomodulatory therapy for PUK/Mooren’s ulcer does not only help in controlling the eye disease, but also increases life expectancy.

*For more on Terrien’s marginal degeneration, see www.nzoptics.co.nz/articles/archive/a-rare-but-profound-cause-of-corneal-thinning

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Professor Charles McGhee for supplying pictures and reviewing this article.

Reference and further reading

- Ogra, S, Sims, J, McGhee, C, Niederer, R. Ocular complications and mortality in peripheral ulcerative keratitis and necrotising scleritis: The role of systemic immunosuppression. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2020; 48: 434– 441.

- Kaufman S, Rizzuti A. Peripheral Corneal Disease. In: Mannis M, Holland E, eds. Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnosis and Managment. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

- Lohchab M, Prakash G, Arora T, Maharana P, Jhanji V, Sharma N, Vajpayee RB. Surgical management of peripheral corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan-Feb;64(1):67-78.

- Cao Y, Zhang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhou H. Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Associated with Autoimmune Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017/07/13 2017;2017:7298026.

- Ding Y, Murri MS, Birdsong OC, Ronquillo Y, Moshirfar M. Terrien marginal degeneration. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2019/03/01/ 2019;64(2):162-174.

- Yang L, Xiao J, Wang J, Zhang H. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Recurrent Mooren’s Ulcer. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017/06/27 2017;2017:8978527.

Dr Haitham Al Mahrouqi is a senior fellow in cornea and anterior segment at the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Auckland. He attained his medical degree at the University of Otago in 2012 before returning to his home country of Oman for ophthalmology training. He has an interest in thinning disorders, particularly corneal ectasia.