Understanding the challenges and opportunities of Māori ocular health

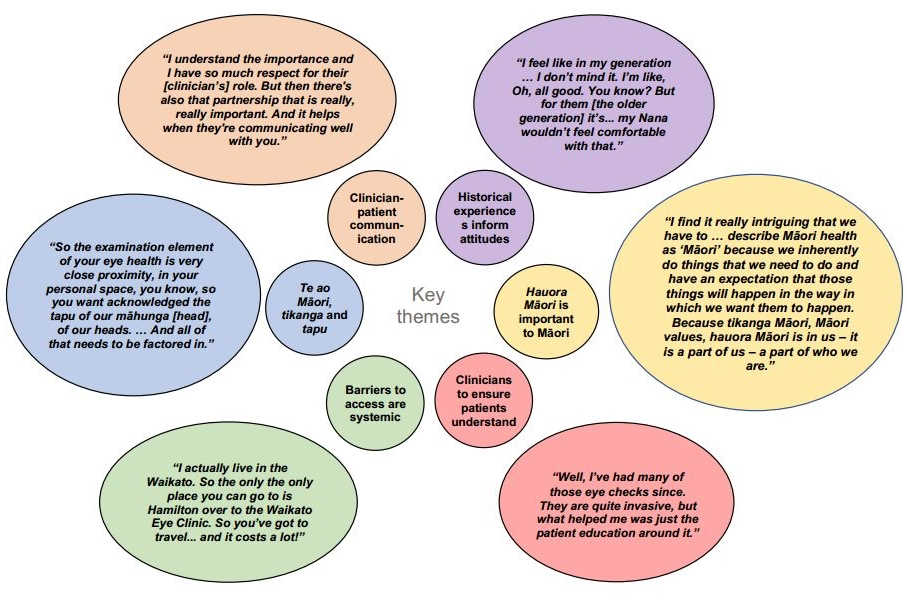

Across Aotearoa, Māori experience significant health inequities compared to non-Māori. Despite advancements in healthcare over the last century Māori continue to experience higher rates of morbidity across almost all diseases, including ocular conditions. Māori are more likely to suffer from diabetic retinopathy, keratoconus and advanced cataracts compared to non-Māori1. Addressing these inequities requires the focused attention of clinicians and researchers and is crucial for fulfilling tāngata whenua rights and Crown obligations. This article explores the specific ocular health challenges faced by Māori, including barriers to accessing eyecare services. By understanding these challenges and implementing targeted interventions we can work towards a healthier, more equitable future for Māori and all of Aotearoa.

Contextualising inequities

Any discussion about Māori inequities requires an understanding of the historical context. More than a millennium ago, Māori arrived in Aotearoa aboard ancient waka hourua (double-hulled voyaging canoes). Waves of European immigrants then began arriving in the early 19th century, which led to extensive sharing of cultures, ideas and relationships. As Pakeha (non-Māori) immigrants continued to increase, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) was created and signed in 1840. This agreement between the British Crown and Māori Rangatira ensures equal opportunities and rights for Māori and British settlers, protection of Māori by the Crown and partnership between Māori and the Crown in the governance of Aotearoa.

Māori health inequities are fundamentally rooted in the historical and ongoing breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which are themselves inextricably connected to the ongoing process of colonisation. The systematic appropriation of Māori land has resulted in unequal power structures within Aotearoa that do not honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi resulting in substantial physical, fiscal and spiritual loss to Māori. The impact of colonisation continues today and the persistent existence of health inequities (including ocular) serves as an ongoing reminder to te kāwanatanga (the government) of its obligation to ensure Māori have the same rights and privileges, including to health, as other New Zealanders. Understanding the connection between colonisation and health is crucial for clinicians treating Māori patients because it provides essential context for today's health disparities and social determinants affecting Māori health.

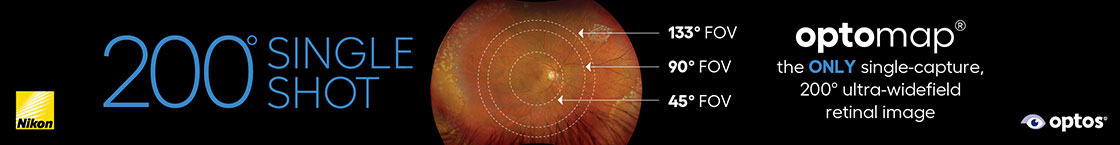

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment in New Zealand's working-age population2. The prevalence of diabetes in Māori is estimated to be roughly three times higher than in non-Māori3. Māori present with more advanced diabetic eye disease at baseline DR assessment, independent of diabetes type; they also experience more severe retinopathy and maculopathy compared to non-Māori and have a higher risk of tractional retinal detachment4. Risk factors for more advanced diabetic eye disease in Māori include a delayed diagnosis of diabetes, delayed referral or uptake of retinal screening, a higher HbA1c and issues related to access4. Currently, there is no comprehensive profile of DR in Aotearoa and the exact burden of DR for Māori is unknown1.

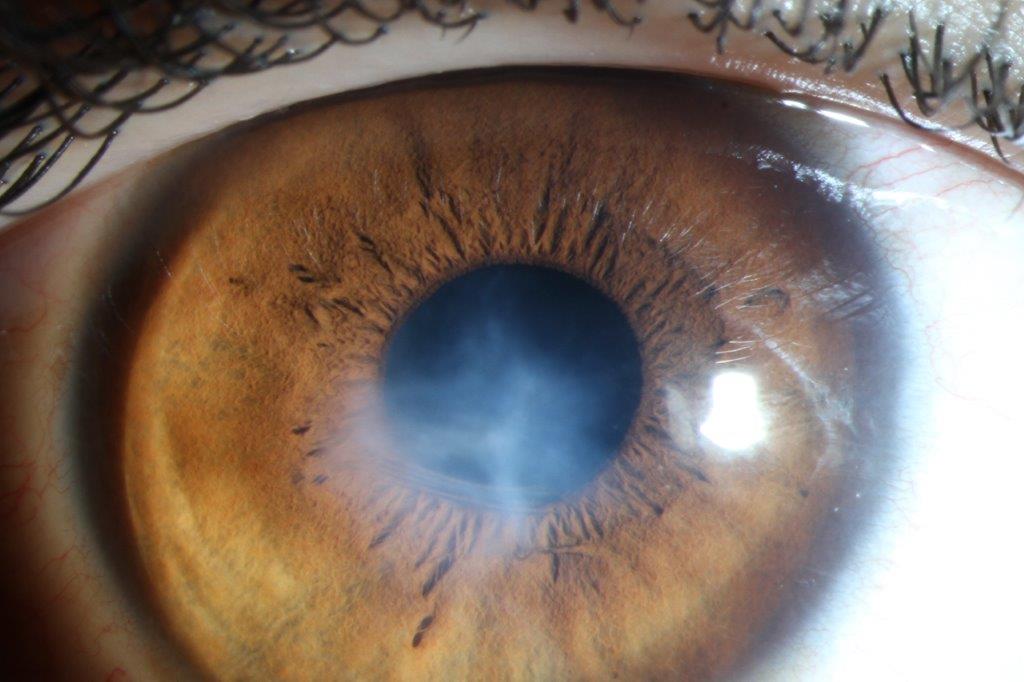

Keratoconus

Keratoconus is a significant cause of ocular morbidity for Māori and results in a significant economic burden to both the patient and healthcare system5,6. Māori experience significantly higher rates of keratoconus and more severe keratoconic disease compared to non-Māori and are more likely to progress to penetrating keratoplasty and at an earlier mean age (27 years) than non-Māori7. The Wellington Keratoconus Study, a prospective cross-sectional study of 1,916 high school students from 20 schools, found keratoconus may affect one in 191 New Zealand adolescents and as many as one in 45 Māori adolescents8. Another large study of keratoconus by Gokul et al prospectively surveyed community optometrists nationwide and identified 1,869 individuals with keratoconus, of whom 22.7% identified as Māori9.

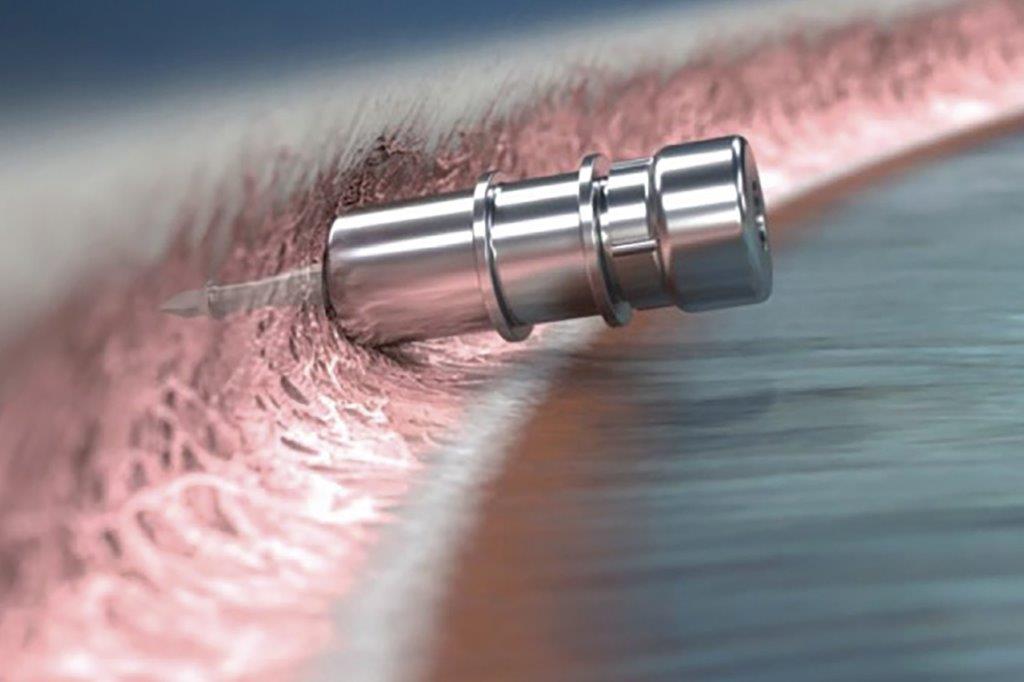

Author Dr Micah Rapata performing collagen crosslinking

Author Dr Micah Rapata performing collagen crosslinking

A significant proportion of keratoconus is first diagnosed, or at least suspected, by optometrists, who refer to tertiary eye services. Given the average cost of an optometry visit is upwards of $70, cost remains a significant barrier to ocular healthcare for many Māori10. Recognising this, policymakers need to formulate strategies to mitigate the late presentation of keratoconus patients to public eye services by providing financial support for Māori to access optometry services10. This would facilitate earlier diagnosis of keratoconus, thereby reducing the need for tertiary interventions such as corneal grafts due to acute corneal hydrops. The high rate of corneal transplantation and hydrops reflects the severity of keratoconic disease experienced by Māori and reinforces the need for better and earlier access to eye health services in Aotearoa.

Cataract

Cataract surgery is the most frequently performed elective surgery in Aotearoa, with more than 30,000 cases performed annually. Cataracts and other lens disorders are thought to be roughly 1.5-2 times as prevalent in Māori compared to non-Māori up to the age of 8411. Māori have worse visual acuity and present with cataract at a younger age compared to non-Māori12,13.

There continue to be significant barriers for Māori to accessing timely referral for cataract surgery, as well as issues in diagnosing, treating and delivering cataract services to Māori equitably throughout Aotearoa1,13.

Cataract eligibility is based on a weighted combination of visual acuity, cataract morphology and patient-reported quality of life to produce a clinical prioritisation and assessment criteria (CPAC) score. Māori make up 13.3% of cataract prioritisation events compared with New Zealanders of European descent at 65.7%13. Although the proportion of prioritisation events for Māori is not significantly different to their proportion in the wider population, Māori have worse visual acuity, more advanced cataracts and more severe visual impairment compared to the wider population at the time of prioritisation13. Earlier onset and severity of cataracts necessitates prioritisation of Māori for cataract surgery on average eight to nine years earlier than the wider population13. Consequently, cataracts have a more significant impact on the working lives of Māori and are more likely to affect whānau, work, health, community and other commitments due to an inability to maintain driving vision standards.

Uncorrected refractive error

Uncorrected refractive error, with the exception of presbyopia, is the most common cause of vision loss in Aotearoa in individuals aged 40 and over (55%)14. However, the incidence of uncorrected refractive error in Māori is currently unknown and thus requires urgent attention from researchers.

According to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists, there is a deficit between Māori and non-Māori in respect to contact lens wear11. This deficit likely reflects the unsubsidised financial cost of an optometrist assessment and associated spectacle/contact lens costs. With the median annual income for Māori being significantly lower than the national average, this economic disparity makes the cost of optometry visits a significant financial burden for many Māori and their whānau, who, with financial constraints themselves, are often required to prioritise essential needs such as housing, food and general medical care over optometry services15.

What can be done?

One way to reduce inequity is through a national eye health survey. Australia’s first national eye health survey was in 2016 and its second is underway. Gambia has had three (1986, 1996, and 2019) and has documented progressive improvements in eye health. To be truly representative, a national eye health survey in Aotearoa would require approximately 6,000 participants across geographically disparate regions. The School of Optometry and Vision Science at the University of Auckland is currently undertaking a pilot Rapid Assessment of Blindness (RAB) study, supported by the Blind and Low Vision Education Network NZ (BLENNZ), to help refine the process for a comprehensive survey 1.

While a national eye health survey can’t address the root causes of health inequities for Māori, it could still be immensely impactful in many ways. It would provide appropriate data to help target those most at risk of avoidable blindness, reduce the economic cost of vision loss, reduce inequity in eye health and eye health service delivery, direct the services to where they are needed most and help develop a sensible, funded eye health-check policy. By providing a detailed and accurate picture of eye health across the nation, a national eye health survey is a critical step towards reducing ocular health inequities and improving overall health outcomes for all New Zealanders, particular Māori.

Conclusion

Māori continue to experience significant disparities in ocular disease, particularly DR, keratoconus and cataracts. Ocular health inequities, along with health inequities in general, are rooted in historical and ongoing grievances relating to breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. A national eye health survey is one way to reduce ocular health inequities by providing comprehensive data, informing targeted interventions and guiding resource allocation. Equity in ocular health is not just a healthcare issue but a vital component of social equity, economic productivity and overall national wellbeing. Addressing these inequities is essential for building a healthy, productive, and cohesive nation that can fully harness the talents and capabilities of all its people.

References

- Rapata M, Cunningham W, Harwood M, Niederer R. Te hauora karu o te iwi Māori: A comprehensive review of Māori eye health in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;51:714–27.

- The Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in primary care. Best Practice Journal. 2010;30:38–50.

- Ministry of Health. Diabetes [Internet]. Diseases and Illnesses. [cited 2022 Oct 24].

- Hill S, Mullins P, Murphy R, et al. Risk factors for progression to referable diabetic eye disease in people with diabetes mellitus in Auckland, New Zealand: a 12-Year retrospective cohort analysis. AJPO

- Rapata M, Cunningham W, Harwood M, Niederer R. Te hauora karu o te iwi Māori: A comprehensive review of Māori eye health in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;51:714–27.

- Rebenitsch R, Kymes S, Walline J, Gordon M. The lifetime economic burden of keratoconus: a decision analysis using a markov model. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:768–73.

- Crawford A, McKelvie J, Craig J, McGhee C, Patel D. Corneal transplantation in Auckland, New Zealand, 1999-2009: Indications, patient characteristics, ethnicity, social deprivation, and access to services. Cornea. 2017 May;36:546–52.

- Papaliʼi-Curtin A, Cox R, Ma T, Woods L, Covello A, Hall R. Keratoconus prevalence among high school students in New Zealand. Cornea. 2019 Nov;38:1382–9.

- Gokul A, Ziaei M, Mathan J, et al. The Aotearoa Research Into Keratoconus Study: geographic distribution, demographics, and clinical characteristics of keratoconus in New Zealand. Cornea. 2021 Feb;

- Rogers J, Kandel H, Harwood M, Vea T, Black J, Ramke J. Access to eye care among adults from an underserved community in Aotearoa New Zealand. Clin Exp Optom. 2023;1–9.

- RANZCO. Māori and Pasifika Eye Health [Internet]. Community Engagement. 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 20].

- Yoon J, Misra S, McGhee C, Patel D. Demographics and ocular biometric characteristics of patients undergoing cataract surgery in Auckland, New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;44:106–13.

- Chilibeck C, Mathan J, Ng S, McKelvie J. Cataract surgery in New Zealand: access to surgery, surgical intervention rates and visual acuity. N Z Med J. 2020 Oct;133:40–9.

- Access Economics. Clear Focus — The economic impact of vision loss in New Zealand in 2009.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2013 Census QuickStats about income [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Oct 20].

Ko Ngātiwai te iwi, ko te uri o Hikihiki te hapu, he uri tênei no Whangaruru. Dr Micah Rapata works as the crosslinking and anterior segment fellow at the University of Auckland and Greenlane Eye Clinic. He has a strong interest in Mãori ocular health and in examining ways to reduce inequity in ocular health outcomes for Māori.