Stargardt: a tangled web of woe

Or why different spectacle prescriptions should never be put into the same or similar frames. By Naomi Meltzer

The phone call started the usual way, with a lady who wanted to “get some advice on the best way to adapt my life as my macular degeneration deteriorates”. I became suspicious when I realised she was only 50 years old and was working full time as a payroll clerk. She had a great computer setup in her home office, which she could not replicate in her workplace, and she was struggling with handwritten forms. She had already given up her beloved hobby of cake decorating and she now found reading too tiring.

I asked her who had told her she had macular degeneration and whether it had been recently checked. Eventually, she admitted Stargardt had been mentioned by an ophthalmologist some 20 years ago, which made a lot more sense to her case and provided a firmer footing to start from. She had worn glasses constantly since childhood and reluctantly gave me permission to call the optometry practice she had seen a year earlier.

The prescription of her latest spectacles was:

- RE -0.75 -4.00 x 90; (VA) 6/12; near add +1.00

- LE plano -5.00 x 75; (VA) 6/120; near add +1.00

When I enquired with the dispensing optician (DO) whether this new pair was single-vision distance, near, or progressive addition, I got the reply that the new pair were single-vision distance and there was a second pair made with the +1.00 add. Interestingly, the DO mentioned in passing that this second pair was in exactly the same frame as the first. Curious, I thought. Perhaps I’d better take my vertometer with me.

Curiouser and curiouser

At first, the patient denied having two pairs of spectacles, insisting she wore one pair for everything, including driving. It turns out this pair was indeed RE +0.25 -4.00 x 90 and LE +1.00 -5.00 x 75, with the +1.00 add – the reading prescription!

Then, from the bedroom drawer she produced the old pair she kept as a spare, vaguely recalling that she’d broken a pair some time ago. This old pair had the prescription RE -0.50 -3.50 x 88 and LE +0.50 -4.50 x 76.

After looking out of the window to compare the distance vision with the two pairs, she broke down in tears and confessed she’d been too scared to see anyone about her vision because it appeared to have deteriorated suddenly. She was terrified to lose her driver’s licence before her 14-year-old son was old enough to drive himself around to his various music and sporting activities and recounted some very scary and sad incidents when she had been unable to see.

This was a clear example of why it’s important not to put different spectacle prescriptions into the same or similar frames as it can lead to confusion and even potential disaster!

But wait – there’s more!

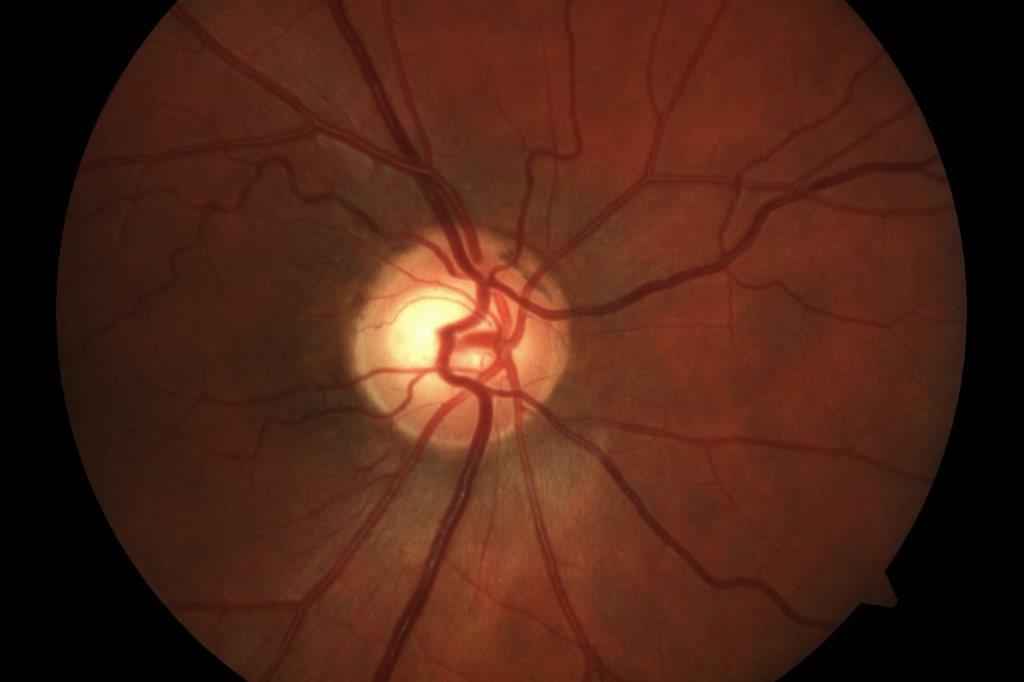

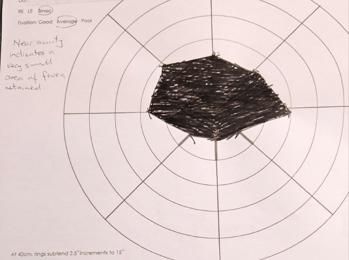

At this point, the plot thickened, with the patient’s binocular functional visual fields (Fig 1) revealing a big central scotoma. Her near acuity on a high-contrast single word chart was N 12 in average room light, improving to N 10 with intense local lighting and better still to N 8+ on a high-contrast sentences chart. However, she was unable to read the N 80 low contrast line on the same chart.

Fig 1. Binocular functional visual fields revealed a big central scotoma

How could she have good high-contrast acuity with such a big central scotoma? I can only surmise that she has a tiny island of fovea left, or maybe several islands, smaller than the central fixation point on the chart and therefore I did not pick it up. Perhaps she also uses eccentric fixation? Obviously, she either needs high magnification to project beyond the central scotoma or maximal contrast enhancement to enable her to use what central vision she has. A new pair of reading glasses with a higher add is not going to offer sufficient improvement.

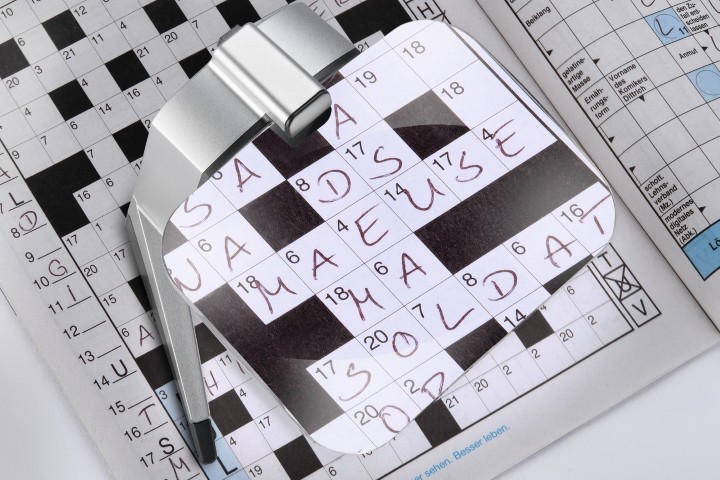

In the end she chose a small, portable video-magnifier, which to her delight solved her work problems of coping with handwritten forms by enhancing the contrast as well as magnifying the print. She can carry this from home to office easily and it enables her to relax with a good book at the end of a stressful day. In addition, she now has a pocket magnifier with a bright LED light to assist her when shopping or reading a menu, which gives her increased independence from relying on her family and friends.

She then told me she was about to go overseas for the first time as a parent helper on her son’s orchestra trip. She was terrified she would not be able to enjoy the experience and would be more of a burden to her son than a helper. A 6 x 16 monocular went a long way to solving that issue for her and the tears came back again – this time from joy – and I struggled to hold back from joining her.

Naomi Meltzer is an experienced optometrist who runs an independent Auckland practice specialising in low-vision consultancy. She is a regular contributor to NZ Optics.