Safe handling and disposal of ophthalmological waste

Following the recent ophthalmic nurses RANZCO NZ meeting in Rotorua, there has been ongoing discussion of how best to handle and dispose of substances used in ophthalmology, particularly intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapies and botulinum toxin (Botox or Dysport). As awareness increases about occupational safety and environmental sustainability, clinical protocols must reflect current evidence and drug classification guidelines.

This article outlines a practical, evidence-based overview of best practices for handling anti-VEGF agents, botulinum toxin and true cytotoxic medications. It highlights the differences between these agents and provides recommendations that ensure staff safety, regulatory compliance and environmental responsibility.

Agent descriptions

Anti-VEGF agents – including bevacizumab, ranibizumab, aflibercept and faricimab – are recombinant humanised monoclonal antibodies, or fusion proteins. They are not considered hazardous in terms of occupational exposure in ophthalmology and there is no systemic toxicity reported during intravitreal use1.

Botulinum toxin is a purified protein derived from bacteria. It works by attaching to nerve endings where they meet muscles and blocking acetylcholine, which helps muscles to contract. In blocking acetylcholine, the muscle becomes temporarily paralysed.

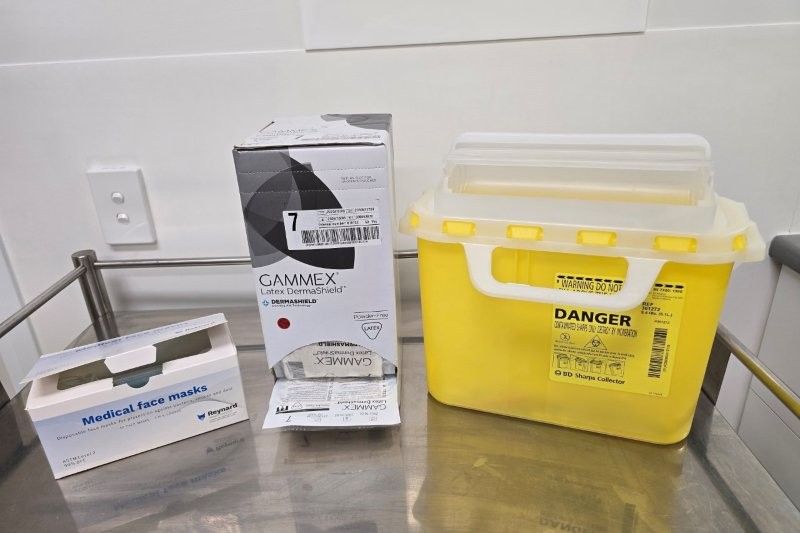

Neither of these agents is classified as cytotoxic or hazardous under guidelines from the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, or other international regulatory bodies. They are administered using sterile techniques and pose minimal risk to staff. For both anti-VEGF agents and botulinum toxin, handling requires no special personal protective equipment (PPE) beyond standard aseptic precautions – such as gloves and masks – and eye protection is not required, as neither poses a splash or aerosol hazard during preparation or administration. Routine disposal via yellow-lidded sharps containers is sufficient, unless contamination with cytotoxic substances occurs2–6.

In contrast, true cytotoxic agents, such as mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which damage or kill rapidly dividing cells, pose well-established occupational hazards, particularly to pregnant staff. Their handling requires specific essential precautions, detailed below. Staff involved in their use should be trained in hazardous drug protocols7.

- Double-gloving with chemo-rated nitrile gloves to minimise dermal exposure

- Use of long-sleeved gowns, eye/face protection and other barrier methods

- Disposal of materials in designated cytotoxic waste bins, following institutional protocols

- Comprehensive staff training in safe handling, spill management and waste procedures.

These steps are critical to safeguarding staff while maintaining high standards of patient care3,8-11.

Matching risk with precaution

For anti-VEGF and botulinum toxin administration, standard PPE – gloves, masks and aseptic technique – is sufficient. There is no evidence to support the need for cytotoxic-level precautions in the routine ophthalmic use of these agents3,4.

A key challenge in clinical environments is fear-driven PPE use. Anecdotal concerns or historical practices have sometimes led to unnecessary or excessive protection. While well-intentioned, this overuse can increase healthcare costs, waste and staff anxiety. Education and clarity on the actual risks can help promote confidence and ensure appropriate PPE is used without overburdening staff or the environment.

Although anti-VEGF agents and botulinum toxin are not classified as hazardous, caution is recommended for pregnant or vulnerable staff, due to limited long-term safety data. While the risk is considered minimal, avoiding preparation or administration during pregnancy is a prudent precaution5,6,12.

Environmental considerations

Correct classification and segregation of waste play a crucial role in reducing environmental impact:

- Anti-VEGF and botulinum toxin waste can be safely discarded in standard sharps containers, unless mixed with cytotoxic substances

- Avoiding unnecessary use of cytotoxic-labelled bins and excessive PPE reduces clinical waste

- These practices align with national and international sustainability goals in healthcare13-16.

Summary

A clear understanding of the pharmacology and occupational risks of ophthalmic agents allows for safe and sustainable clinical practice. Anti-VEGF and botulinum toxin therapies, while potent and effective, are not classified as hazardous or cytotoxic in ophthalmology. However, caution is advised for pregnant or vulnerable individuals who may be present during the preparation or administration of these medications. Aligning PPE and waste disposal protocols with actual risk promotes safety, reduces clinical waste and supports environmentally responsible healthcare delivery. By following evidence-based guidelines and fostering ongoing education, ophthalmology teams can confidently maintain high standards of care while ensuring staff wellbeing and regulatory compliance.

References

- Velez-Montoya R, et al. Lack of systemic toxicity of anti-VEGF intravitreal injections. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):495–503.

- European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Expert Consensus Statement on Intravitreal Injections. 2020.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). ASHP Guidelines on Handling Hazardous Drugs. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(7):e34–e71.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for Safe Handling of Biologics. 2016.

- Allergan, an AbbVie Company. Botox Product Monograph. 2022.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). List of Antineoplastic and Other Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings. 2020.

- New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO). Guideline: Safe Handling of Hazardous Drugs. Wellington, New Zealand: NZNO; 2020.

- Connor TH, MacKenzie BA, DeBord DG, et al. NIOSH Workplace Solutions: Personal protective equipment used when handling hazardous drugs. 2014.

- International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners (ISOPP). Standards of Practice. 2016.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Safe Handling of Hazardous Drugs. 2018.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health-care Waste Management. 2018.

- Saeed MU, Tameem A, Probert C, et al. Safety considerations for intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy in pregnant or breastfeeding patients. Eye. 2014;28(6):695–700.

- Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice: Environmental consequences of protective protocols. BMJ. 2020;370:m2736.

- Peaky M, Johnson R, Lee D. Environmental footprint of healthcare waste and sustainability in ophthalmic procedures. J Environ Health. 2022;85(3):24–31.

- Slawomirski L, Auraaen A, Klazinga N. Waste not, want not: Promoting value and sustainability in healthcare. OECD Health Working Papers. 2020; No. 104.

- Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand. Healthcare Waste Management – National Policy. 2021.

Fiona Suter is a nurse practitioner with more than 30 years’ experience in ophthalmology in the UK and New Zealand. She practices privately at Nelson Eye Surgeons and is contracted to work at Te Whatu Ora Nelson Marlborough and Westport.