Reframing sustainable optometry

UK independent optometrist Simon Berry is on a sustainability crusade. After years of research, he decided to share practical ways for DOs and optoms to do their bit for the planet.

Sustainability is a universal topic, attracting a vast spectrum of opinions. We each choose the sources we trust, but it's not as simple as aligning yourself with Greta Thunberg or Donald Trump. Let’s be honest, sustainability brings conflicts in business (do we really want our patients to constantly reuse their frames instead of buying new ones from us?) and in health. I have a patient who will not wear daily disposable contact lenses because she hates to think she’s throwing away single-use plastic, and she recently had an ulcer that ate through a quarter of the thickness of her cornea!

My focus has been on the ethical issues of running a practice. It's one thing for me to buy a cheap shirt, but if I stock frames made in an unethical manner, I’m endorsing them. So I decided to ascertain the provenance and sustainability of my stock by developing a questionnaire for my suppliers to rate the ethicality of their products. About half of them responded. I haven't stopped using the other half, but in the last few years I’ve only opened new accounts with those who comply.

At that time, about six years ago, nobody really seemed to care about these issues. Now we're facing the opposite problem – sustainability is a commodity many consumers want, which means it can be exploited. Because of demand, sustainable plastics such as PET are increasing in cost, in some cases to almost double that of a non-sustainable equivalent. Some companies have even applied ‘greenwashing’, where their product is made to look more environmentally friendly than it really is. Kevin Brady, an environmental author and adjunct professor at the School of Industrial Design at Carleton University in Canada, asks his students to investigate products claiming to be ethical and sustainable as part of his course. With no independent organisation verifying each company’s claims, the students usually find just 20% of them are accurate.

As optometrists, we have to trust our suppliers, even though in many cases they are distributors and too far removed from the manufacturer to have the information we might want. Complicating that, a supplier might not tell us the whole story or gloss over the issues they don't want us to know, while shouting about the ones they do.

Public vs professional attitudes

I also surveyed fellow optometrists and patients from my practice to see where their attitudes overlapped. I found 92% of patients said they would pay more for a frame that was guaranteed to be sustainable, while 65% of optometry staff said they would be willing to take less profit for such a product (which is probably not necessary if there are enough consumers who want it). But when asked if sustainability influenced their frame buying, 69% of patients said they'd never thought about it! However, 12% cited sustainability as their main concern when buying frames, so that should give us a bit more confidence to start sourcing sustainable brands.

Being sustainable is a mindset. It doesn't just mean buying a few recycled frames. Are we looking at reducing our energy consumption, for example? Do we pay a fair wage to our staff and support them when things go wrong? As a service industry, we exist because our community supports us, so are we seeking out local suppliers? Are we looking at ways of reducing consumables, going paperless, or using recycled paper, e-mail or text reminders to reduce postage?

How we dispose of our waste is also an important part of the picture. Practices have a responsibility to segregate waste into hazardous and non-hazardous clinical waste. The former is incinerated at over 850⁰C. That takes a lot of energy, but there are companies, such as Project Kea, using energy recovery techniques and recycling some of the metals. Landfill has always been the worst option and each waste company has a different ethos to ensure the least amount of waste goes to landfill. Do a bit of digging and use the one that does it best.

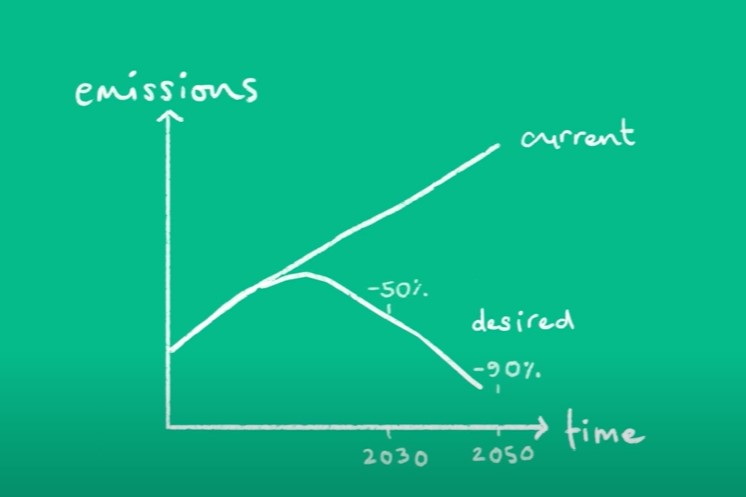

One way we can quantify our impact on the planet is knowing our carbon footprint, a concept popularised by multinational oil giant BP’s advertising campaign to try and shift the blame of fossil fuels’ impact onto the consumer! Undoubtedly the biggest carbon usage I contribute to is the mix of stock I source, and the spectacle frames manufactured in China, Brazil, Italy and South Korea. One of our industry’s quirks is when a frame is marked as made in a particular country, it’s only where the most expensive part of production took place – the rest can come from anywhere. Even frames from one company’s collection can be made from a combination of raw materials from different sources, so it's impossible to work out the carbon footprint of a frame… Which is exactly why I’m trying to do it.

I’m working with Durham University to develop an algorithm to allow optometrists to roughly work out any frame’s carbon footprint. If we get it right, we'll be able to educate patients about their frames and work out an entire practice’s footprint to offset the amount of carbon it’s responsible for.

Practical plastic reduction

The plastic waste in our oceans is disgraceful but it’s not the material’s only environmental impact. An estimated 6% of global oil production goes into making new plastics, pumping 390 million tonnes of CO2 (about 15% of the global carbon budget) into the atmosphere annually. A lot of plastic still goes into landfill, where its toxic constituents can leach into the soil, while incinerated plastic pollutes the air and marine environment with dioxins. However, the amount of higher-grade plastic created for frames is arguably justified for the length of time that it serves its purpose – as optometrists, we don't really use anything equivalent to a plastic straw or drinks bottle.

For an average patient, let’s overestimate the weight of plastic in their frame and double that to allow for manufacturing waste – that’s 50g of plastic for a frame that will last a patient about two years. If we add a couple of minims, Goldman tip, lenses, packaging, the case and all those guarantee cards the lens companies give us, we could easily get to 150-160g. The average person in the UK throws away about 85g of plastic packaging every day – that’s 62kg over two years. Unfortunately, the least sustainable plastics are the ones used in cheaper frames, so a child who breaks their glasses every six weeks over that two-year lifespan would use around 2.6kg of plastic – 17 times as much!

Lots of people are trying to make demo lenses more eco-friendly, but why don't we just stop using them altogether? Their only purpose is to show patients what a frame would look like with lenses, but we can do that in other ways. In my survey, I asked whether demo lenses were relevant in a modern optometry practice. Half the optometry staff said patients expected to see a true representation of their glasses, yet 88% of patients said they’d rather demo lenses weren't used.

If we make an effort to use sustainable materials in cheaper frames and packaging and avoid demo lenses, we could avoid a lot of new plastic being created. It takes just 12% of the energy to recycle plastic than to create it from scratch. We can't easily recycle bioplastics, which are big in our industry and, unfortunately, cellulose acetate is never likely to be part of a widespread recycling scheme. That said, when it’s plant based, it’s biodegradable and can be composted, but only if you can guarantee that it is pure, which is one of the huge problems in our industry – we don't really know what the majority of our frames are made from.

Every item of clothing has a label that tells you its main components, yet, despite a spectacle frame being in contact with the patient’s skin every minute of every day, there’s little information available about what the frame is made from or which dyes have been used. So you get contaminated waste streams because you don't really know what's in the recycling bin. Some frame companies, such as Coral Eyewear or MonkeyGlasses, recycle their own plastics since they already know their frames’ exact composition. Probably more significantly, Mazzucchelli has introduced its first sustainable plastic, partly made from recycled acetate.

In terms of reuse, it's worth mentioning the charities that take old glasses, although the World Health Organisation decided shipping them to the developing world was not the best use of resources. In partnership with Lions Recycle For Sight, Specsavers recycle old frames, while the Foureyes Foundation works with Lions clubs to refurbish frames for New Zealand schoolkids and with Volunteer Ophthalmic Services Overseas (VOSO) for use in the Pacific Islands.

The bottom line

Tortoiseshell is a material we've all got synthetic examples of on our frame racks. The shell has been used as far back as Ancient Egypt to make nice things. Our industry was a heavy user of tortoiseshell, part of a beautiful creature with a potential lifespan of 50 years. But, having been on this planet for 120 million years and sharing it with humans for the last 300,000 years, sea turtles are now critically endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Their population has declined by over 80% in the last 100 years, primarily because we find their shell nice to look at. They were hunted to the brink of extinction until the trade of its shell was finally made illegal in 1992.

So if a relatively modest industry such as ours has enough influence to help bring a creature like this to the brink of extinction, it can also positively use its influence to bring about change.

Sustainable optometry deserves to be at the core of what we do.

This is an edited version of Simon Berry’s lecture for the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

Simon Berry runs a carbon-neutral, independent optometry practice in Durham, England. He has a particular interest in sustainability and innovative adaptations for performing optometry examinations for patients with special needs.