Putting the ‘action’ into ‘refraction’

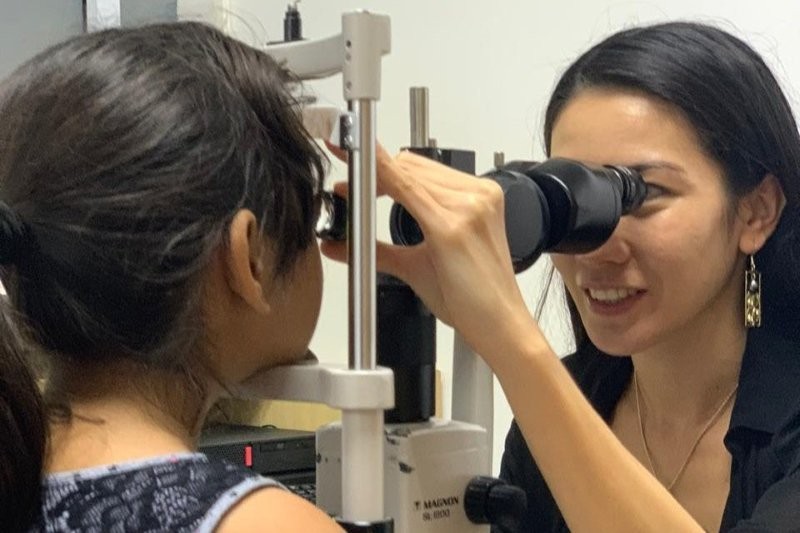

Sydney-based ophthalmologist Dr Sarah Crowe is the one-woman powerhouse behind OOXii, a charity empowering non-optometrists to refract and supply spectacles in remote regions. Drew Jones asked why she persuades local workers to carry her custom phoropter and lens kit for five hours through jungles.

The current paradigm for getting glasses hasn't changed in almost 100 years, says Dr Sarah Crowe. “You have to see a professional, you get a prescription, the lenses are custom made, then you have to go back and pick them up. None of that works in a remote or poor community.” Even if a patient could find an optometrist close enough and travel to see them, they certainly couldn’t travel twice and they can't afford the glasses anyway, she says. “That whole system fails a billion people around the world – a billion people who are vision impaired just because they can't get glasses. To me, that's just not acceptable.”

The name OOXii (pronounced ‘ook-see’) comes from ‘OO’ being the round glasses multiplying your two eyes, explains Dr Crowe, the charity’s founder. Her original company is called 4eyes Vision, but a rebrand was deemed necessary. “In some countries that’s regarded as derogatory – they don’t understand the Australian sense of humour!”

OOXii is the charitable arm of 4eyes, itself a social enterprise which returns 50% of any profits back to OOXii, which holds the intellectual property for Dr Crowe’s patented refraction-testing wheel. The two entities work closely together to fund and deliver glasses to people who need them in poorly resourced areas. Each portable 4eyes testing kit includes the refraction wheel, similar to a simplified phoropter, and a supply of frames and lenses. It can service up to 200 people, delivering an eye test and dispensing glasses in just 25 minutes, says Dr Crowe.

A recent OOXii Papua New Guinea project involved community health workers wading across a river with Dr Crowe’s testing kit then walking five hours to the village of Sirorata to supply glasses to people who’ve never had them before. “We’ve done a few projects in Papua New Guinea because our main source of funds to date has been the Kokoda Track Foundation, a charity working there. They’ve basically got us through initial prototyping, so that’s why we’ve ended up doing all our studies there. And since that’s been highly successful, we’re looking at scaling up and moving to other countries.”

Plugging the eyecare gap

The way we traditionally test for refractive error is full of jargon and unnecessary complexities, she says. “So what I've done is basically dumbed it down so that anyone can follow the prompts on our app and get what you need, because it's a subjective refraction.” The lens kits contain around 1,000 pre-cut lenses, to cover 95% of refractive errors the teams encounter.

Concerned that optometrists might feel affronted by her simplification of one element of their role, Dr Crowe points out that in Papua New Guinea there are an estimated 12 million people and just eight optometrists. Her drive to do something was born directly from her own time working in the Solomon Islands, experiencing the devastating effects of preventable blindness on individuals and their families, she says.

According to World Health Organization research, 53% of avoidable vision impairment is simply due to a lack of access to glasses. There are lots of places where no form of eye healthcare is available, so it's not fair that the people living there can't get glasses either, says Dr Crowe. “Obviously, for any of us in this profession, getting eye healthcare to everyone is the ideal. But the real-world situation is that those people who can’t access eye healthcare shouldn't be deprived of the vision that makes getting an education or a livelihood possible.”

OOXii is like a stopgap measure, she explains, until a country or a region can provide better eyecare to all its people.

Making a spectacle

In collaboration with an industrial designer, Dr Crowe also designed the kit’s adjustable frames, which last September won an Australian Good Design Award for social impact. “They’re made of stainless steel, they don't have screws in the hinges and they're very durable, light and comfortable.”

Dr Crowe is now selling the frames to raise money to support the foundation. “I've been wearing them myself for the last five years. It's the first time in my life that people have come up to me in the street and said, ‘Those glasses are really cool, where did you get them?’ So we've started a crowdfunding campaign to sell them and use the proceeds to fund our work.

“There's so much money out there but everyone wants to support children's cancer, gene therapy or AI… all very worthy, but cheap glasses are not really sexy.” Yet a study by LEK Consulting on one of OOXii’s pilot projects in Papua New Guinea found that for every dollar put into the glasses project, there was a $91 benefit to the community. “That sort of return in Western terms is huge,” says Dr Crowe. “But where we work, $91 goes much further.”

What OOXii needs now is enough money to scale up manufacturing of the testing kits and to hire people to run the logistics and the supply chain, she says. “I'm an ophthalmologist, not an operations manager!”

For now, Dr Crowe says she’s paying for everything out of her own pocket. “We're at the point the startup world calls ‘the valley of death’, where everything's ready to go and you just need this big boost of capital to get it off the ground.”

For more information, or to support OOxii’s work, visit: www.4eyesvision.org