Long-term trends in keratoplasty in Aotearoa

It has been more than 30 years since the New Zealand National Eye Bank (NZNEB) was established; in that time, Stats NZ has reported a dramatic 41% increase in New Zealand’s population. The NZNEB acquires, stores and distributes ocular tissue for the whole country and holds a comprehensive database in relation to transplant recipient demographics and indications for keratoplasty. This database allows us to track and report on the national trends in keratoplasty relative to the growing population1.

When we account for this significant rise in population, we see that as a whole, New Zealand’s ophthalmology services have increased the total number of transplants performed accordingly (Fig 1)1. However, there have been developments over the last 15 years that have resulted in major changes in the type of keratoplasty performed, as well as the primary indication for transplantation and recipient age.

Fig 1. Common primary presenting indications for corneal transplantation and the total number of transplants each year, reported per 100,000 population

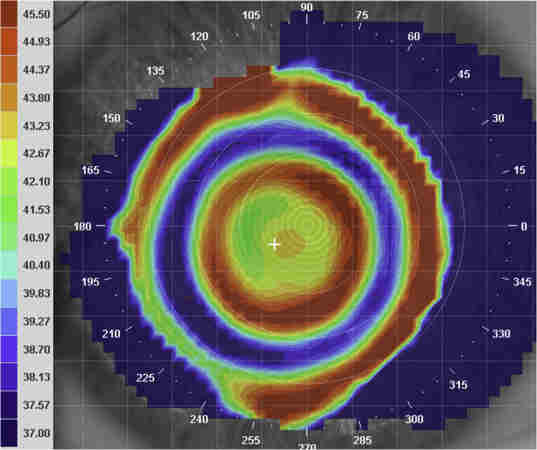

For decades, over 90% of all transplants performed in New Zealand were penetrating keratoplasties (Fig 2 and 3)1, and the majority were for keratoconus (Fig 1)1. Corneal crosslinking is a procedure that has been proven to halt or minimise the progression of keratoconus; in New Zealand, we estimate that more than 3,000 eyes with progressive keratoconus have now been treated with this procedure. Since keratoconus was historically the most common primary indication for transplantation, we might reasonably expect to see this indication slowly fall as these crosslinking-treated eyes no longer progress to transplantation. Initially, access to corneal crosslinking in New Zealand was limited, but most large DHBs now provide this service such that we are beginning to see this downstream effect on keratoconus-related corneal transplantation (Fig 1)1. Additional research is underway into socioeconomic factors related to keratoconus and corneal crosslinking in New Zealand – Dr Lize Angelo’s doctoral studies with the ophthalmology dept at the University of Auckland, being one example. Results from this work will help address barriers to diagnosis, attendance and treatment of keratoconus.

The lifespan of a corneal transplant depends on several factors but, in general, New Zealand has a penetrating keratoplasty survival rate of 87.9% at two years2, while studies from Australia report 10-year survival rates of 60%3. Transplant recipients that require repeat keratoplasty for graft failure or decompensation fall under ‘regraft’ as the primary indication for transplantation, regardless of their initial presenting diagnosis. Naturally, since New Zealand has been performing a large number of transplants for more than 30 years, we are seeing an increasing number of these earlier transplants presenting for regraft (Fig 1)1. This observation, combined with the effect of corneal crosslinking mentioned earlier, is also reflected by the 2019 milestone, when regraft overtook keratoconus as the most common indication for corneal transplantation.

In addition to the rate changes for keratoconus and regraft, we also note the rate of bullous keratoplasty progressing to corneal transplantation is slowly decreasing over time (Fig 1)1. The vast majority of these cases were identified as pseudophakic, which traditionally refers to the development of irreversible oedema after cataract surgery. We interpret this trend to be a direct result of improved technology and advancing surgical technique across the country, as well as an increased awareness of minimising endothelial cell damage during surgery.

The development of endothelial keratoplasty to treat endothelial failure, graft exhaustion or corneal dystrophies proved to be a less invasive procedure than penetrating keratoplasty. It also carries a smaller risk of graft rejection and keratitis and results in faster visual recovery and excellent refractive outcomes.

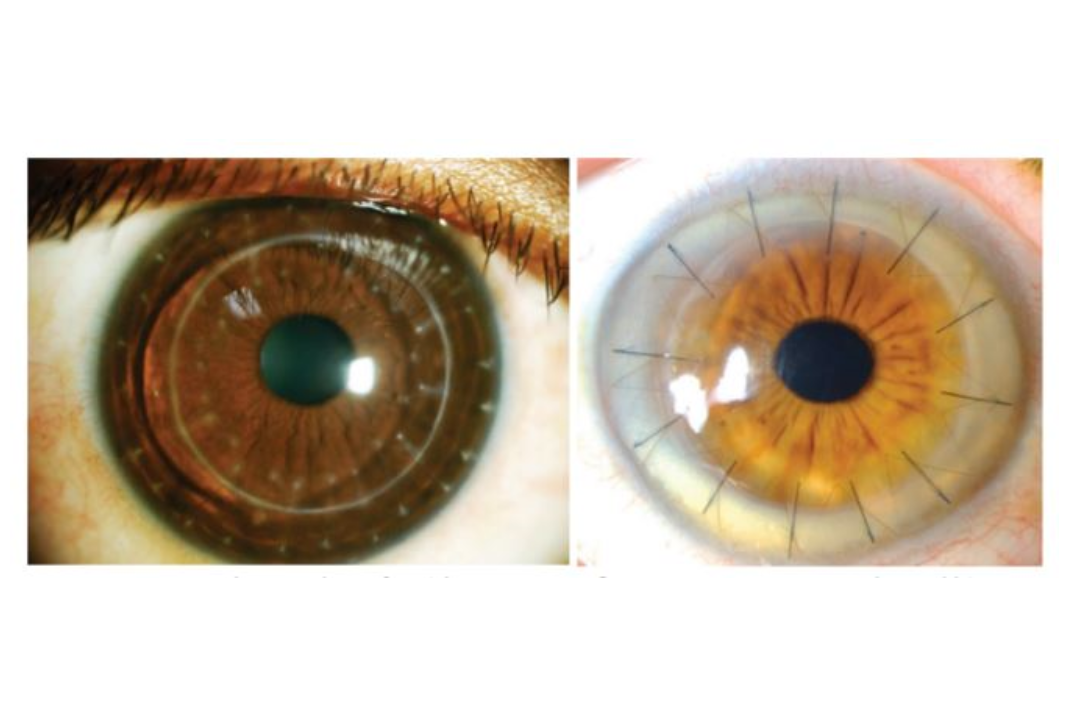

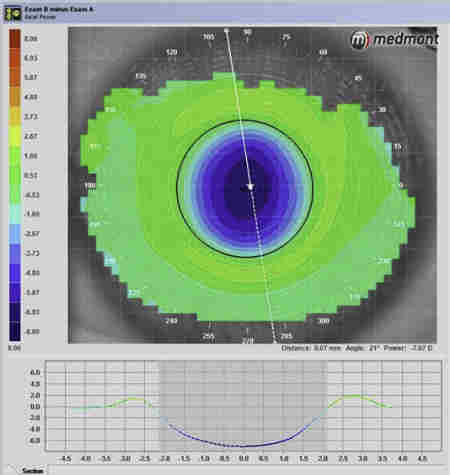

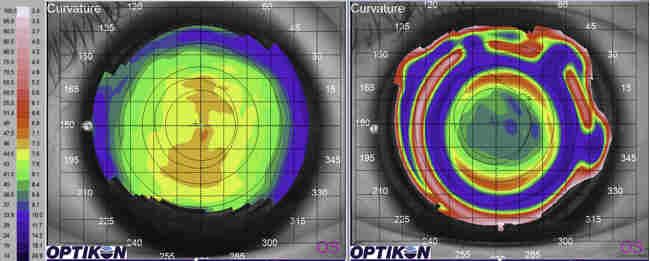

The first type of endothelial transplant in New Zealand was Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) in 2007. Early on, this procedure proved to be technically demanding since surgeons themselves prepared this delicate tissue for partial thickness transplantation. Graft perforation or damage was a feared complication during the manual tissue preparation but, fortunately, technological advances weren’t far behind and NZNEB began to pre-cut corneas for this technique (Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK)), which resulted in shorter surgical time, improved patient outcomes (Fig 4) and therefore, increased utility (Fig 3)1. In the last decade, DSAEK was performed primarily for Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (48.5%), followed by regrafts (23%) and bullous keratopathy (19.6%), whereas prior to 2007, penetrating keratoplasty would have been performed for all of these indications.

Fig 3. Transplant procedures performed each year as a percentage. Note the significant rise in Descemet’s stripping (automated) endothelial keratoplasty (DS(A)EK), the corresponding fall in penetrating keratoplasty (PK) and a small rise from 2016 for Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK)

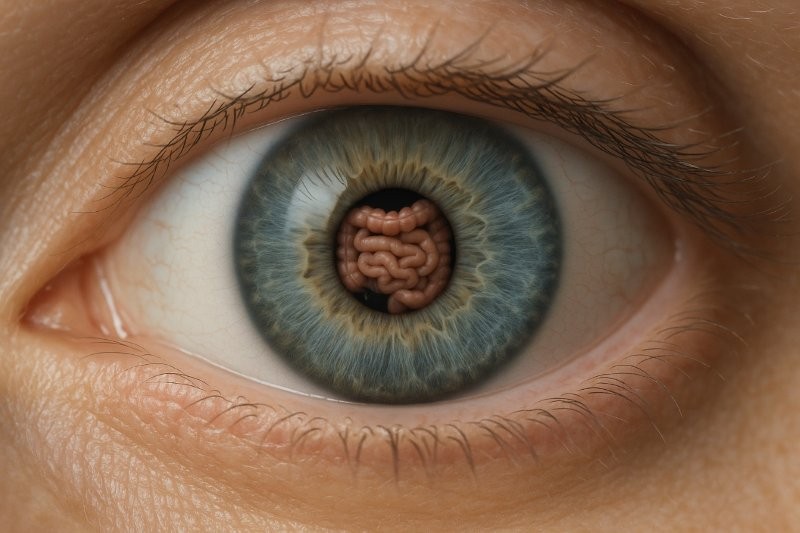

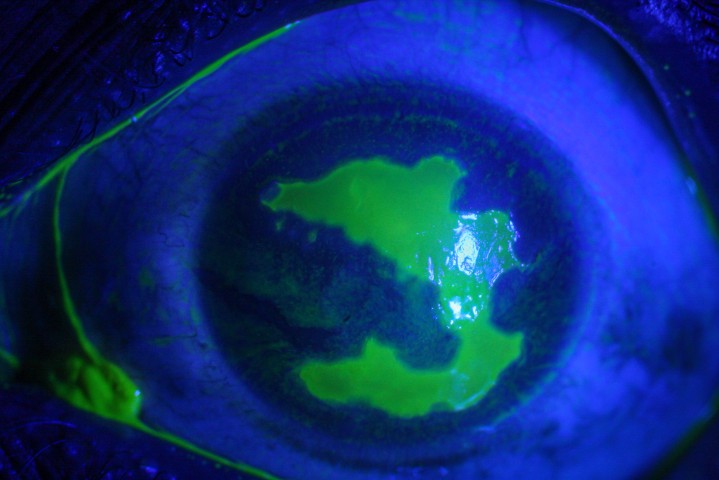

Fig 4. Transplant recipient one month after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty performed for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. Images show a clear graft with sutures securing the entry wounds (subsequently removed three months postoperatively)

Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) was also introduced in 2007 but was rarely performed until 2016 (Fig 3)1. Since then, the adoption of this technique into regular practice in New Zealand has not been as significant as observed overseas4, possibly due to the technical challenges surgeons face with the procedure and in preparing the graft, since the NZNEB does not yet pre-prepare DMEK tissue.

These major developments in transplantation techniques have also heavily influenced the age profile of patients that receive this vision-restoring surgery. Indications such as Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy, regraft and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy are typically older than those with keratoconus, which correlates with the observed trends in transplant recipient age (Fig 5)1.

Fig 5. Transplant recipients by age group showing an increasing number of recipients over the age of 40 years, particularly those aged 60-79 years

Conclusion

Through the longitudinal study of trends in corneal transplantation, we appreciate how ophthalmology as a surgical speciality continues to evolve. This is not just due to new keratoplasty techniques, but also the result of high-quality surgical training in phacoemulsification and the downstream effect of procedures such as corneal crosslinking for keratoconus.

Future areas of interest include the development of cultured endothelial cells injected together with a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor5 which will likely change keratoplasty trends yet again. This procedure may not be as far away as we think – in just one generation it is amazing to reflect on how far ophthalmology has evolved and it is equally exciting to consider where science and research will take us next on the transplantation path. The future certainly looks clear and bright!

References

- Chilibeck CM, Brookes NH, Gokul A, Kim BZ, Twohill HC, Moffatt SL, Pendergrast DG, McGhee CNJ. Changing Trends in Corneal Transplantation in Aotearoa/New Zealand, 1991 to 2020: Effects of Population Growth, Cataract Surgery, Endothelial Keratoplasty, and Corneal Cross-Linking for Keratoconus. Cornea 2021;in press.

- Crawford AZ, Krishnan T, Ormonde SE, Patel DV, McGhee CN. Corneal Transplantation in New Zealand 2000 to 2009. Cornea 2018;37(3):290–5. Doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001481.

- Williams KA, Lowe MT, Keane MC, Jones VJ, Loh RS, Coster DJ. The Australian Corneal Graft Registry 2012 Report. Adelaide. Snap Printing, 2012 2014.

- Chan SWS, Yucel Y, Gupta N. New trends in corneal transplants at the University of Toronto. Can J Ophthalmol 2018;53(6):580–7. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.02.023.

- Numa K, Imai K, Ueno M, et al. Five-Year Follow-up of First 11 Patients Undergoing Injection of Cultured Corneal Endothelial Cells for Corneal Endothelial Failure. Ophthalmology 2021;128(4):504–14. Doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.09.002.

Dr Corina Chilibeck is the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel corneal and anterior segment clinical research fellow in the Department of Ophthalmology, headed by Professor Charles McGhee, at the University of Auckland. Her doctoral studies are based on aspects of cataract surgery, surgical risk, and surgical training, including the Eyesi Surgical simulator.