Exploring the interplay between glaucoma and DED

Glaucoma is a potentially blinding condition for which multiple treatment options are available to slow or halt progression of the disease. However, many of these treatment options increase the risk of glaucoma therapy-related ocular surface disease (GTR-OSD). Dry eye disease (DED) is a significant ocular comorbidity affecting 40-60% of glaucoma patients worldwide¹. Glaucoma has been identified as a significant risk factor for DED with an odds ratio of 1.77 (95% CI: 1.17 - 2.69) in a large meta-analysis².

Why is glaucoma associated with an increased risk of DED?

Evidence supports glaucoma severity and higher intraocular pressure as risk factors for the development of DED³. There is also significant evidence that glaucoma treatments are a further risk factor for DED. In particular, the greater the number of glaucoma medications used, and the greater the total number of daily anti-glaucoma drops used, have both been identified as specific risk factors for DED¹.

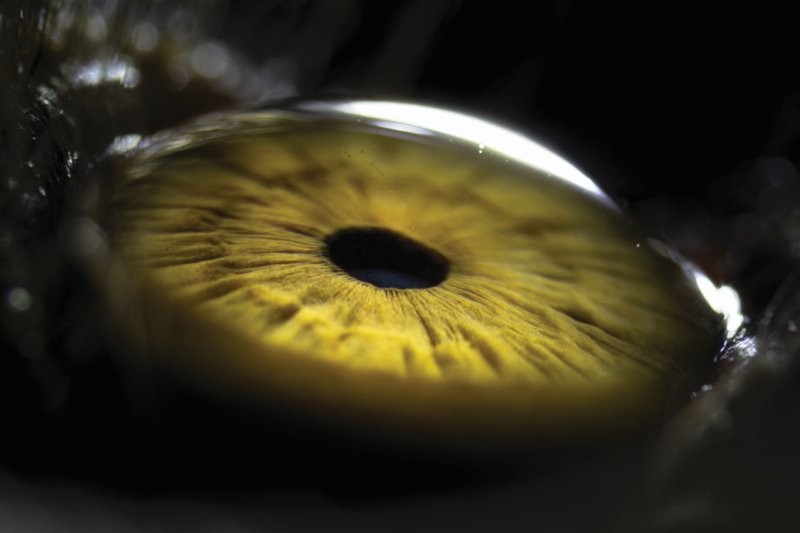

Topical glaucoma medications are a common and proven strategy to reduce intraocular pressure (Fig 1). However, this treatment method can profoundly disrupt the homeostasis of the tear film. The cumulative effects of medications, preservatives and excipients can alter the underlying cellular structures, resulting in tear film instability and abnormalities of the ocular surface¹,⁴,⁵. The tear film is a complex and dynamic multilayered structure that plays a role in the optimal refraction of light, nourishment of the ocular surface epithelia and removal of waste products⁵. Topical glaucoma medications with preservatives can negatively impact the goblet cells, meibomian glands, ocular surface epithelia and the corneal sub-basal nerve plexus, leading to ocular symptoms and abnormal corneal fluorescein staining (Fig 2).

The toxic effect of preservatives in glaucoma medications can cause loss of goblet cells leading to reduced mucin production, increased tear film instability and increased risk of DED⁴,⁶,⁷. Preservatives in glaucoma medications also have a toxic effect on the meibomian glands, causing meibomian gland drop out and decreased expressibility of meibum⁴,⁶. When the corneal epithelium is exposed to glaucoma medication, it undergoes changes leading to an increase in inflammatory marker expression, a reduction in cellular density in the superficial layer and increase in cellular density in the basal layer alongside associated intracellular changes, particularly at the limbus⁶,⁷,⁸,⁹. The tear film can subsequently be negatively impacted through an imbalance in electrolyte production and subsequent modification of the aqueous layer of the tear film. There is also some limited evidence that preserved glaucoma medications may result in a reduction in the density of nerves in the corneal sub-basal nerve plexus⁸,¹⁰.

Fig 2. Diffuse punctate corneal fluorescein staining and limbal filament in a patient with severe DED

Prostaglandin analogues have also been associated with periorbitopathy, characterised by a constellation of eyelid and orbital changes including deepening of the upper lid sulcus, inferior scleral show and upper lid ptosis (Fig 3). In particular, iatrogenic tightening of the lids can lead to secondary dry eye due to an incomplete blink and lagophthalmos²,¹¹.

Fig 3. Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy with deepening of the upper lid sulcus, inferior scleral show and upper lid ptosis

Chronic inflammatory changes from glaucoma medications have been shown to impact their therapeutic efficacy¹. Patients with glaucoma and DED have been shown to have worse adherence to anti-glaucoma medications than those with glaucoma but without DED⁷. GTR-DED can also reduce quality of life due to the associated symptoms of burning, pain, stinging and irritation. These symptoms can impact general well-being and alter visual function and acuity¹,⁷. As might be expected, a positive correlation has also been identified between the severity of DED and the number of IOP-lowering medications used⁷,¹³.

Trabeculectomy is a potential risk factor for DED, although there is conflicting evidence in the published literature, with multiple studies linking trabeculectomy with GTR-OSD, resulting in individuals having increased tear osmolarity and a four-fold increase in the use of ocular lubricants¹,¹⁴. However, it is difficult to differentiate bleb-associated dysesthesia from dry eye symptoms, both of which could lead to an increase in the use of ocular lubricants. On the contrary, other evidence suggests trabeculectomy supports an increase in goblet cell density and a decrease in limbal dendritic cell and meibomian gland density, which correspond to an overall objective improvement of the ocular surface¹⁵. It seems plausible that the reduction of topical medications following a successful trabeculectomy could improve the ocular surface⁹.

Management

If a patient has complained of dry eye symptoms since commencing glaucoma drop use or has pre-existing DED, it is appropriate to suggest alternative pressure-lowering management, such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT). This treatment is very well tolerated with minimal side effects and has become a first-line treatment option for patients with open angles¹⁶.

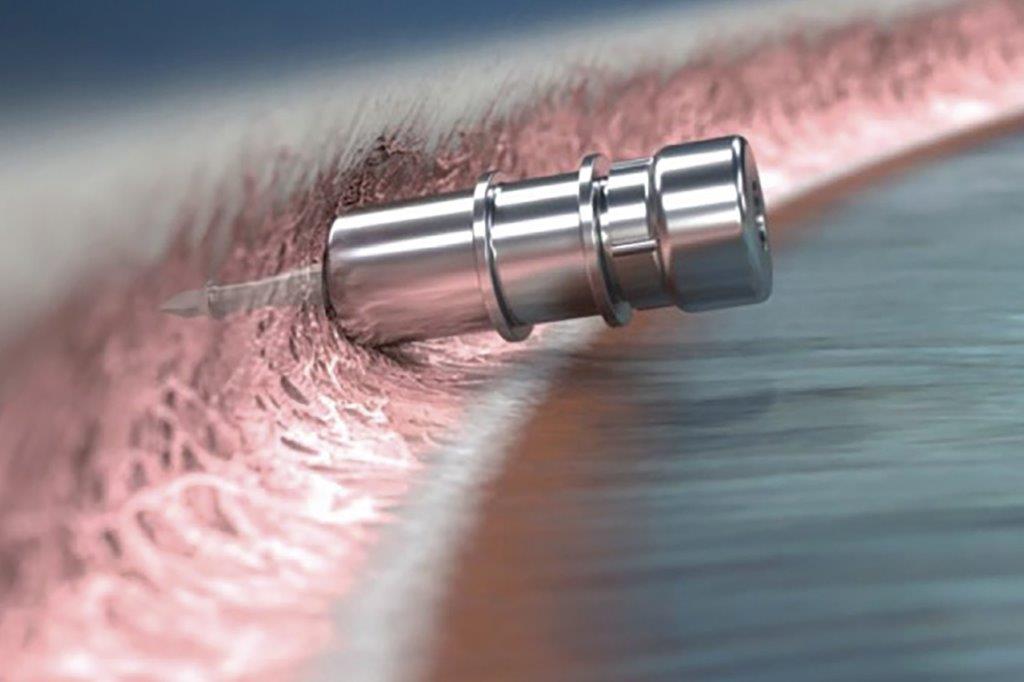

For patients with glaucoma and DED, standard dry eye treatments can be recommended, including good eyelid-hygiene habits, improving environmental conditions, intentional blinking and using artificial tears. If a patient is using preserved glaucoma drops, they would ideally use preservative-free artificial tears to avoid increasing the load of preservative and associated ocular surface toxicity. Punctal plugs can be a very useful option for patients who require frequent use of ocular lubricants as they may reduce the number of artificial tears needed¹⁷. Patients can also be trialled on combination drops to reduce the number of glaucoma medications used and daily drops required and minimise the preservative load.

Further treatments from a specialised dry eye provider can be considered for patients with persistent dry eye symptoms, despite initial therapy. These include intense pulsed light (IPL) or a thermal pulsation procedure to treat meibomian gland dysfunction¹⁸. Likewise, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) is an effective option for reducing IOP and significantly reduces the number of anti-glaucoma eye drops required, therefore improving DED¹⁹.

Preservative-free glaucoma medication has the advantage of reducing the side effects of traditional pressure-lowering drops with preservatives. Studies have shown that patients using preservative-free therapy experienced fewer overall symptoms and reduced incidence of fluctuating vision, ocular discomfort, itchiness and foreign-body sensation¹,³,²⁰. Furthermore, there is evidence that switching to preservative-free anti-glaucoma drops can significantly improve signs and symptoms of preservative intolerance and DED⁷. Despite the ever-mounting evidence of preservative-free pressure-lowering glaucoma drops being effective at reducing intraocular pressure and the risk of DED, New Zealand does not currently have any funded preservative-free glaucoma medications (apart from pilocarpine 2%, which is generally used in clinic rather than prescribed to the patient). Even for patients who are willing to pay for preservative-free medications, these are very difficult to obtain and rely on a pharmacy being willing to either compound the medication or source it from overseas, which means, ultimately, that these preservative-free medications are cost-prohibitive for many patients. Hopefully, preservative-free glaucoma medications will become more widely available and less expensive in New Zealand in the future. For patients on preserved glaucoma medications, it has been demonstrated that rigorous DED treatment can result in statistically significant improvement in bulbar redness and a reduction in dry eye severity scores despite continuation of preserved glaucoma drops²¹.

Jeremy Holyer is a year-six medical student at the University of Auckland.

Dr Jay Meyer is a consultant ophthalmologist at Eye Institute and Te Whatu Ora Auckland, with a special interest in corneal diseases and glaucoma, and a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland.

References:

- Nijm LM, De Benito-Llopis L, Rossi GC, Vajaranant TS, Coroneo MT. Understanding the dual dilemma of dry eye and glaucoma: an international review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2020 Dec;9(6):481-490.

- Procianoy F, Lang M and Bocaccio F. Lower eyelid horizontal tightening in prostaglandin associated periorbitopathy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37: S76-S79.

- Gomes JAP, Azar DT, Baudouin C, Efron N, Hirayama M, Horwath-Winter J, et al. TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):511-538.

- Wong ABC, Wang MTM, Liu K, Prime ZJ, Danesh-Meyer HV, Craig JP. Exploring topical anti-glaucoma medication effects on the ocular surface in the context of the current understanding of dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2018; 16(3); 289-293.

- Bland HC, Moilanen JA, Ekholm FS, Paananen RO. Investigating the Role of Specific Tear Film Lipids Connected to Dry Eye Syndrome: A Study on O-Acyl-ω-hydroxy Fatty Acids and Diesters. ACS Publications. 2019;35(9):3545-3552.

- Mastropasqua R, Agnifili L, Mastropasqua L. Structural and molecular tear film changes in glaucoma. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(22):4225-4240.

- Baudouin C, Labbé A, Liang H, Pauly A, Brignole-Baudouin F. Preservatives in eyedrops: The good, the bad and the ugly. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(4):312-334.

- Jiménez-Ortiz HF, Fernández NT, Fernández Escamez CS, Perucho Martinez S, Crespo Carballés MJ. The effects of ocular hypotensive drugs on the cornea: An in vivo analysis with confocal microscopy. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2013 Nov;88(11):423-32.

- Nijm LM, Schweitzer J, Gould Blackmore J. Glaucoma and Dry Eye Disease: Opportunity to Assess and Treat. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023 Oct 17;17:3063-3076.

- Martone G, Frezzotti P, Tosi GM, Traversi C, Mittica V, Malandrini A, et al. An in vivo confocal microscopy analysis of effects of topical antiglaucoma therapy with preservative on corneal innervation and morphology. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Apr;147(4):725-735.e1.

- Berke SJ. PAP: New Concerns for Prostaglandin Use. Rev. Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct;19(10):70-74.

- Qian L, Wei W. Identified risk factors for dry eye syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 19;17(8):e0271267.

- Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, Stewart JA, Stewart WC, Jasek MC. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea. 2010 Jun;29(6):618-621.

- Lee SY, Wong T, Chua J. Boo C, Soh YF, Tong L. Effect of chronic anti-glaucoma medications and trabeculectomy on tear osmolarity. Eye. 2013;27:1142-1150.

- Agnifili L, Brescia L, Oddone F, Sacchi M, D’Ugo E, Di Marzio G, et al. The ocular surface after successful glaucoma filtration surgery: a clinical, in vivo confocal microscopy, and immune-cytology study. Sci Rep. 2019 Aug;9:11299.

- Clement CI. Initial treatment: prostaglandin analog or selective laser trabeculoplasty. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2012 Sep-Dec;6(3):99-103.

- Ervin AM, Law A, Pucker AD. Punctal occlusion for dry eye syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 26;6(6):CD006775

- Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, Oribio-Quinto C, Milans-Del-Bosch A, Perez-Garcia P, Morales-Fernandez L, Garcia-Bella J, Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, et al. Intense pulsed light-based treatment for the improvement of symptoms in glaucoma patients treated with hypotensive eye drops. Eye Vis (Lond). 2022 Apr;9(1):12.

- Jones L, Maes N, Qidwai U, Ratnarajan G. Impact of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery on the ocular surface and quality of life in patients with glaucoma. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2023 Feb 13; 15:25158414231152765.

- Konstas AG, Boboridis KG, Athanasopoulos GP, Haidich AB, Voudouragkaki IC, Pagkalidou E, et al. Changing from preserved to preservative-free cyclosporine 0.1% enhanced triple glaucoma therapy: impact on ocular surface disease—a randomized controlled trial. Eye (Lond). 2023 Dec;37(17):3666-3674.

- Mylla Boso AL, Gasperi E, Fernandes L, Costa VP, Alves M. Impact of ocular surface disease treatment in patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:103-111.