Digital twins predict healthcare outcomes

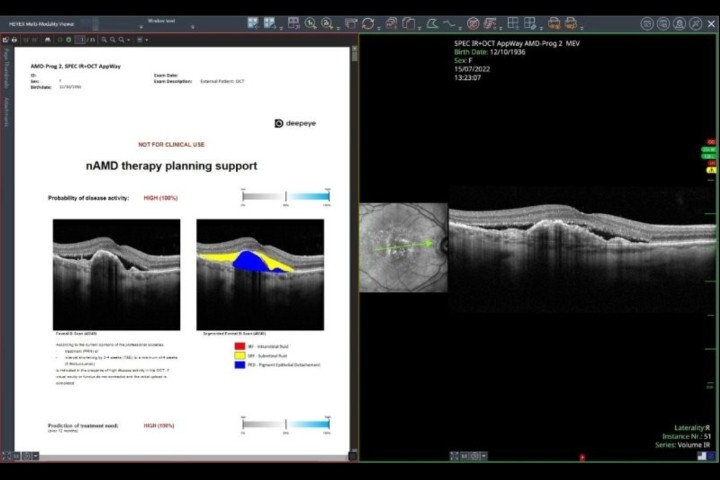

Researchers from The Alfred hospital in Melbourne and the Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI) explored how human digital twins – computerised models of individual patients – can predict responses to surgery or medication.

To demonstrate the usefulness of these ‘crash test dummies’, Professor David McGiffin, a cardiothoracic expert from The Alfred, described the challenge of treating the “nasty” lung condition, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. “When patients have a blood clot in the lung, in 96% of cases the clot is broken down and resorbed by the patient’s own mechanisms,” said Prof McGiffin. “But in about 4%, the clot causes obstruction in the arteries to the lung, which is ultimately fatal.” He added, “We’re often in a conundrum: is an operation going to be a good idea or not?” Human digital twins could help by simulating the outcomes of surgery, said Prof McGiffin.

At ABI, Professor Merryn Tawhai and her team are working on digital models of lungs. “A digital twin could be particularly useful with outlier cases – the 20% of patients who leave doctors scratching their heads,” she explained. “These people consume a lot of resources and end up with poor quality of life. A digital twin lets us test different treatment options before making a decision.”

The University of Auckland also reported progress in using digital twins for joint replacements and diabetes management. A $4 million Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment-backed project is focused on creating individualised digital twins to manage diabetes at home. These will link to an on-screen robot, or ‘digital health navigator’, to provide health advice.

The human digital twin project has been ongoing for 40 years and Prof Tawhai said she is confident we’ll soon be using them routinely. “I think back to my childhood and Star Trek,” she said. “When somebody got ill, there was that little handheld device that scanned them and they knew what was wrong and how to treat it. We’re not quite there yet, but we’re along that pathway. Five, 10, 15 years from now, we could scan a part of you and instantly determine your condition and treatment plan.”