Digital eye strain: take a break, repeat

The dominating presence of digital devices is shaping our functional lives today. Their prolonged use has well-documented adverse effects on our body and mind1,2, including ocular health3.

Around 92% of New Zealand’s adult population has a smartphone, making it one the most widely used digital devices in the country. New Zealanders between the ages of 16 and 64 spend almost 6.5 hours daily on the internet4. A report from the Programme for International Student Assessment comparing 72 countries showed 15-year-old New Zealanders spend a staggering 42 hours a week on the internet, more than their peers in other countries except Denmark, Sweden and Chile5. The penetration of digital devices in all strata of socio-economic status as well as age group puts a significant proportion of the world’s population at risk of developing digital eye strain (DES).

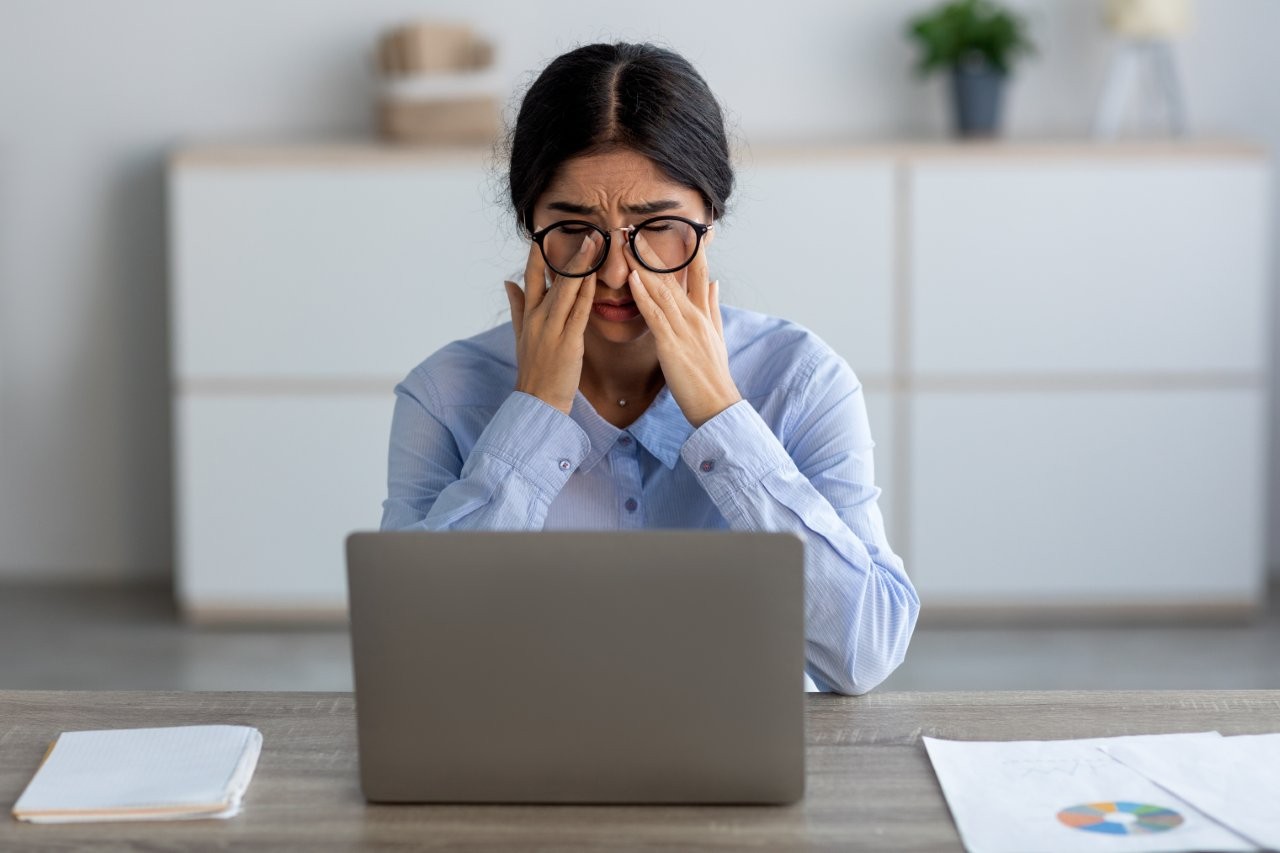

In recent years DES has become one of the most commonly used terms to describe the eye discomfort associated with prolonged viewing of digital devices. Uncomfortable eyes can reduce quality of life and DES is an increasingly likely culprit. DES also reduces work productivity, with as little as 20 minutes of continuous digital viewing/tasks being enough to trigger DES6. Depending on the duration and frequency of digital viewing, the symptoms can persist and intensify and even damage the ocular surface if left unresolved.

Common ocular signs and symptoms for DES include redness, watering, transiently blurred vision, dry and itchy eyes, tired eyes, glare and difficulty in focusing. It’s evident these are non-specific to DES and often overlap with other ophthalmic conditions, such as dry eye disease and ocular allergy, for example. Varying prevalence rates for DES are reported in the literature, which is not entirely surprising given the absence of a standardised definition or criteria for its identification until recently. The recent TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of the digital environment on the ocular surface consensus report has attempted to address this, defining digital eye strain as, ‘the development or exacerbation of recurrent ocular symptoms and/or signs related specifically to digital device screen viewing’3. With this definition, the importance of differentiating eye strain caused specifically by digital screen viewing from other underlying conditions is emphasised. Adoption of this definition by clinicians stands to offer patients improved consistency in diagnosis and reduce variability in reported prevalence rates in future.

Blinking, humidity to combat DES

Research indicates DES tends to escalate with extended periods of digital work. To mitigate symptoms, it’s recommended the duration of uninterrupted digital screen use is minimised by taking regular breaks3. Digital tasks have also been associated with reduced blink rates compared with those while relaxing or performing a non-digital reading task7. The quality of blinks is also affected when performing a digital task, with a higher rate of incomplete blinking observed8,9. Appropriate blinking is vital to maintain the delicate balance of the tear film and preserve ocular surface health. The symptoms of DES are often transient and may reduce or go away when eyes are given a break from digital viewing tasks. When performed consistently, something as simple as taking a 20-second break after performing a 20-minute digital task and looking at an object 20 feet away (the so-called ‘20-20-20 rule’) has been found to be effective in reducing DES10. One of the studies undertaken by the University of Auckland’s Ocular Surface Laboratory (OSL) team, reported in September 2022’s NZ Optics’ dry eye feature, demonstrated the benefits of blink reminders facilitated by a smartphone-based application. Such strategies may be worthy of consideration by clinicians hoping to improve blinking habits among their patients experiencing DES.

Another study by the OSL team demonstrated that increasing humidity in the work environment had benefits in reducing digital eye strain. With just a modest increase in relative humidity locally, a desktop humidifier showed potential to improve tear-film stability and subjective comfort during computer use11.

Although a complex multifactorial condition, DES can be handled with simple solutions. The current evidence about ocular signs and symptoms associated with DES are suggestive but not diagnostic. Hence, the digital environment subcommittee of the recent TFOS Lifestyle Workshop suggests that until robust evidence is established with long-term, high-quality research, a simple line of questioning to confirm that the patient develops or worsens ocular signs and symptoms specifically during digital device use can be an indication for DES3. Frequent breaks, limiting digital viewing times, blinking fully and frequently and increasing relative humidity while working on digital devices are some simple solutions to tackle DES.

Focus on the Ocular Surface is brought to you by the Ocular Surface Laboratory at the University of Auckland in collaboration with the BCLA

References

1. Gulu M, Yagin F, Gocer I, Yapici H, Ayyildiz E, Clemente F, et al. Exploring obesity, physical activity, and digital game addiction levels among adolescents: a study on machine learning-based prediction of digital game addiction. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1097145.

2. Cimke S, Gurkan D, Sirganci G. Determination of the psychometric properties of the digital addiction scale for children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2023;71:1-5.

3. Wolffsohn J, Lingham G, Downie L, Huntjens B, Inomata T, Jivraj S, et al. TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of the digital environment on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2023; In press.

4. Available from: www.energise.co.nz/blog/internet-usage-new-zealand/

5. PISA 2018: Digital devices and student outcomes in New Zealand schools. Available from: www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/schooling/pisa-2018-digital-devices-and-student-outcomes

6. Daum K, Clore K, Simms S, Vesely J, Wilczek D, Spittle B, et al. Productivity associated with visual status of computer users. Optometry. 2004;75(1):33-47.

7. Tsubota K, Nakamori K. Dry eyes and video display terminals. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(8):584.

8. Golebiowski B, Long J, Harrison K, Lee A, Chidi-Egboka N, Asper L. Smartphone use and effects on tear film, blinking and binocular vision. Curr Eye Res. 2020;45(4):428-34.

9. Yin Z, Liu B, Hao D, Yang L, Feng Y. Evaluation of VDT-Induced Visual Fatigue by Automatic Detection of Blink Features. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(3).

10. Talens-Estarelles C, Cervino A, Garcia-Lazaro S, Fogelton A, Sheppard A, Wolffsohn J. The effects of breaks on digital eye strain, dry eye and binocular vision: testing the 20-20-20 rule. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2023;46(2):101744.

11. Wang M, Chan E, Ea L, Kam C, Lu Y, Misra S, et al. Randomized trial of desktop humidifier for dry eye relief in computer users. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(11):1052-7.

Dr Kalika Bandamwar is a post-doctoral research fellow with OSL, in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Auckland, and a fellow of the British Contact Lens Association. Her research interests include dry eye disease, ocular surface and contact lenses.