DED in space: bringing a tear to the sky

Symptoms of dry eye disease (DED), comprising eye irritation, strain and blurred vision, are a prevalent ocular issue reported by about 30% of astronauts on long-term space missions¹.

An Australasian-European research team, working in collaboration with the German Aerospace Center (DLR), is the first to focus on DED in space using parabolic flights as a stepping stone towards in-orbit research. These special flights create microgravity, allowing the team to conduct experiments, using a finely tuned parabolic flight trajectory. Together with ocular surface specialist, the University of Auckland’s Professor Jennifer Craig, we recently travelled to Bordeaux to study DED in a space-like environment on board the Novespace flying laboratory in France.

The space environment presents unique challenges to ocular health, due primarily to microgravity. Microgravity affects fluid distribution, leading to upper body fluid shifts and facial tissue swelling. This alters the anatomy and physiology of the ocular surface and its drainage, potentially impacting tear film dynamics.

The microgravitational shift of fluid upwards into the head and neck region can cause eyelid changes, potentially impacting blinking, meibomian gland function and lipid layer stability. This may affect tear drainage, leading to an altered tear volume and dry eye symptoms. Additionally, changes in the nasolacrimal drainage system can contribute to tear film instability and the low humidity environment, with its exposure to floating dust, artificial lighting and screens, can present further risks to the ocular surface, while the immune system may be more susceptible to inflammation and oxidative stress.

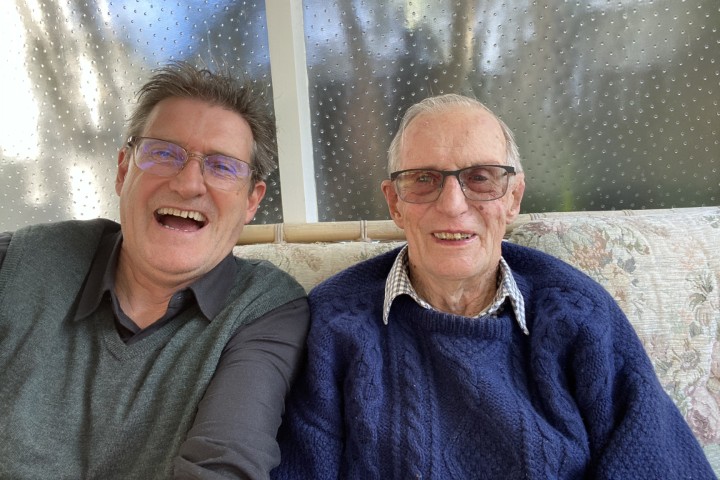

Prof Jennifer Craig conducting a zero-gravity ocular surface exam, courtesy of Novespace and DLR

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station have self-reported eye discomfort, burning sensations and blurred vision, all indicative of dry eye. Since current specialised diagnostic tools have limited applicability in space, diagnosing DED relies heavily on these self-reports, making early detection challenging.

Several strategies have been explored to manage DED symptoms in astronauts, but most have limitations in this unique environment in regard to their application, their need for consumables or their creation of waste. The eye drops and artificial tears conventionally used as tear film supplements are challenging to apply in a microgravity setting. In-flight eye exercises and ocular massage have been suggested to improve lid function and stimulate lacrimal gland activity, while warm compresses could improve meibomian gland function, enhance lipid layer stability and promote healthy and hydrated eyelids and ocular surface. Neurostimulation is also being investigated as a potential sustainable countermeasure.

The current knowledge of DED in space is limited, so continued research is important to ensure the wellbeing and safety of astronauts on future missions. Ongoing collaborations between researchers, optometrists and ophthalmologists will lead to valuable insights and improved therapies, with knowledge from space research likely to have applications on Earth for the benefit of all patients.

Reference

- Ax T, Ganse B, Fries F, Szentmáry N, de Paiva C, March de Ribot F, Jensen S, Seitz B, Millar T. Dry eye disease in astronauts: a narrative review. Front Physiol. 2023 Oct 19;14:1281327.

Dr Timon Ax, a PhD student at Western Sydney University, Australia, is leading the research into DED in space in collaboration with DLR. He completed his medical training at Saarland University in Germany.

Dr Francesc March de Ribot is a consultant ophthalmologist at Dunedin Hospital and an Associate Professor of ophthalmology with Otago University, New Zealand, and Girona University, Spain.