Castor oil for blepharitis

Blepharitis is one of the most common ophthalmic conditions, characterised by chronic inflammation of the eyelid tissues and affecting the eyelashes, meibomian glands and ocular surface. Causative and contributing mechanisms are diverse and include bacterial over-colonisation, a destabilised tear film, infestation with Demodex, atopy and seborrhoea and associated over-activation of host immune and inflammatory responses. However, these factors are only moderately well understood. Patients present with lid margin itching, burning, flaking, crusting, redness, photophobia and epiphora. Overall, blepharitis is often associated with a reduction in quality of life1,2.

Acute blepharitis flare ups are commonly treated with topical antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents, while regular eyelid hygiene and heat-based therapy are considered indispensable for ongoing symptomatic control. However, these strategies tend to be either palliative or limited by microbial resistance and unwanted side effects. Additionally, long-term patient adherence to home-based therapy is notoriously problematic. Innovative interventions that target the underlying causes of blepharitis are thus highly sought after3-5.

Castor oil properties and use

Castor oil is a natural derivative of the Ricinus communis plant, an ancient ethno-pharmaceutical with anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, antioxidant, antimicrobial and insecticidal properties6-10. Extracted or pressed from the plant beans, the main component in castor oil is ricinoleic acid, along with various other oils, fatty acids, vitamins and trace elements. A natural triglyceride, this hydroxylated unsaturated fatty acid possesses surfactant, cleansing, skin conditioning and emulsion-stabilising properties¹¹. It is used industrially, as well as for medical purposes in wound dressings, as a solvent for intramuscular injections and as a drug delivery vehicle. Ophthalmic applications involve castor oil as an emollient or vehicle in eye drop formulations, mostly in conjunction with cyclosporine. In this context, castor oil was serendipitously discovered to address tear film lipid insufficiency and instability and has been proposed as a management option for dry eye disease and meibomian gland dysfunction12-16.

A promising alternative to conventional eye drops is the external application of agents such as liposomal sprays or manuka honey*. These formulations have demonstrated benefits in managing ocular surface disease, owing to the presumed migration of the active ingredient across the lid margin into the tear film and onto the ocular surface17,18. In anterior blepharitis, the chronic inflammation of lash follicles is associated with eyelash thinning, whitening, madarosis and trichiasis. Lid hygiene has a positive impact by decreasing inflammation¹⁹. It was therefore hypothesised that the periocular application of castor oil might be advantageous. Its anti-inflammatory nature may directly target the downstream, chronic, low-grade inflammation associated with blepharitis, while its purported ability to address tear film lipid deficiency secondary to meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), through lipid supplementation, may further contribute to management of the condition.

The limited therapeutic options for blepharitis, coupled with growing interest in natural remedies, provided a nexus of opportunity for researchers in the Ocular Surface Laboratory (OSL) and collaborators to investigate the potential efficacy of castor oil for the management of blepharitis in a randomised controlled trial, recently published in The Ocular Surface journal20.

Study design

Twenty-six participants (53% female, mean age: 38 ± 21 years, between 20 and 79 years) with one or more clinical signs of anterior blepharitis and MGD were recruited into the randomised controlled trial. Participants were randomly assigned to apply unpreserved, 100% cold-pressed castor oil (Lotus Garden Botanicals) to either the left or the right eye, twice daily, for a period of four weeks. The fellow eye received no intervention as a control.

Instructions on the application of a thin film of castor oil on the eyelid skin using a rollerball applicator were provided (Fig 1). Castor oil was applied twice a day, 30 minutes before eye cosmetic wear, if worn, in the morning and following make-up removal in the evening. Participants were asked not to use castor oil on the day of the one-month follow-up visit to avoid unmasking the investigator. Bottles were weighed at baseline and at follow-up as a measure of patient compliance.

Clinical measurements followed the TFOS DEWS II diagnostic consensus recommendations and were performed at baseline and on day 28. Symptoms were assessed using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) and the five-item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). Bulbar conjunctival hyperaemia, tear meniscus height, non-invasive tear film breakup time and tear film lipid layer grade were assessed using the Keratograph 5M (Oculus). The tear film lipid layer thickness was evaluated with the Lipiview ocular surface interferometer (Johnson & Johnson) and tear film osmolarity was measured with a clinical osmometer (Tearlab).

A slit lamp biomicroscopy examination was conducted to assess lid margin and eyelash abnormalities, including lid margin thickening, rounding, notching, foaming, telangiectasia, staphylococcal and seborrhoeic lash crusting, Demodex lash cylindrical dandruff, madarosis, trichiasis and meibomian gland capping. Corneal, conjunctival and lid margin staining was assessed using sodium fluorescein and lissamine green clinical dyes. Meibum quality and meibomian gland expressibility of the inferior eyelid were assessed using the Meibomian Gland Evaluator (Johnson & Johnson). Infrared meibography images were recorded from everted eyelids using the Keratograph 5M, while Demodex presence was determined by lash epilation and light microscopic analysis.

Study results

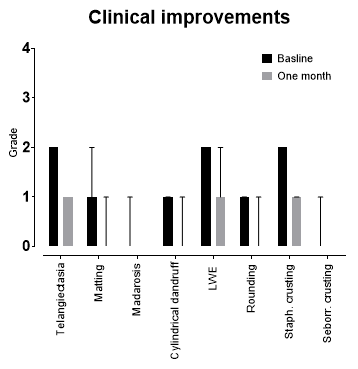

After four weeks of castor oil use, significant improvements in symptoms were reflected in improved OSDI (19.8 ± 13.7 versus 14.0 ± 12.4) and DEQ-5 (9.4 ± 3.1 versus 8.2 ± 3.3) scores (p<0.01). Treated eyes showed significant improvements in telangiectasia, eyelash matting, madarosis, cylindrical dandruff and lid wiper epitheliopathy grades (p<0.01) (Fig 2). Improvements in lid margin rounding, staphylococcal and seborrheic eyelash crusting were noted in both treated and control eyes (p<0.05). No significant changes were observed in tear film parameters, bulbar conjunctival hyperaemia, lid margin notching, foaming, trichiasis, Demodex presence, corneal and conjunctival staining, or meibomian gland characteristics (p>0.05). All returned bottles showed significant weight reduction, reflecting good treatment compliance (p<0.001).

Fig 2. Selected clinical improvements after one month of castor oil use (all p<0.05). Lid margin thickening, telangiectasia, eyelash matting, madarosis, cylindrical dandruff crusting and lid wiper epitheliopathy effects were limited to the treated eyes; lid margin rounding, staphylococcal and seborrheic eyelash crusting improved in both treated and control eyes. Grades defined as 0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe. Data presented as median; error bars indicate interquartile range.

Study conclusions

This novel study demonstrated that a four-week, twice-daily treatment regime with castor oil applied to the periocular skin yielded clinical improvements in ocular surface signs and symptoms in patients with mild to moderate anterior blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. The rollerball castor oil applicator was convenient and well tolerated and no adverse events or visual blurring were reported.

The pathogenesis of blepharitis involves complex hypersensitivity reactions and immune responses, enabling multiple possible angles for castor oil to elicit the observed improvements. The bioactivity of castor oil may effectively interrupt the vicious cycle of ocular surface disease through reducing bacterial over-colonisation, supporting the tear film lipid layer and tear film stability and reducing ocular surface friction at the lid margin. These effects may have added to the intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties of castor oil, further attenuating the blepharitic inflammatory responses. Some findings however, such as the improvements observed in the untreated eyes or the lack of an effect on Demodex presence despite the registered reduction in eyelash crusting, require further inquiry. Previous studies have found improved tear film stability and lipid layer thickness following castor oil use in emulsion drops. These effects were not observed in the current study, possibly as a result of the differing application method. The periocular rollerball application, however, might be more convenient for some patients and provide a more controlled dosing modality. This external application may yield similar benefits to those observed with liposomal sprays as artificial tear supplements, or for manuka honey micro-emulsion as a blepharitis treatment. As an unpreserved formulation, castor oil may also help circumvent common toxicity or allergic reaction side effects associated with more conventional, artificially preserved agents.

While further long-term, placebo-controlled studies are needed to establish the specific mechanisms behind its efficacy, overall, castor oil was found to be an effective strategy for reducing signs and symptoms associated with chronic blepharitis. The simple and convenient periocular application of 100% pure, cold-pressed castor oil was deemed a safe, natural, affordable and effective management option.

Previous OSL studies have demonstrated the value of harnessing the benefits of natural remedies through robust scientific inquiry. This arena provides significant potential for the development of further, safe and effective natural treatment modalities for ocular surface disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge current and previous OSL members who contributed to this research, including Marna Claassen, Lauren Curd and Alice Jackson who undertook this research as a BOptom honours project, Dr Michael Wang and Grant Watters, as well as all study participants who took part. The authors are also grateful to Dr Emma Sandford whose passion for natural ophthalmic healthcare served as the inspiration for this project.

References

- McCulley JP, Shine WE. Eyelid disorders: the meibomian gland, blepharitis, and contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens 2003; 29: S93-95.

- Buchholz P, Steeds CS, Stern LS, et al. Utility assessment to measure the impact of dry eye disease.OculSurf 2006; 4: 155–161.

- Lindsley K, Matsumura S,HatefE, et al. Interventions for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2012; 16: 1–117.

- PflugfelderSC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. Ocul Surf 2014; 12: 273–284.

- Duncan K,JengBH. Medical management of blepharitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2015; 26: 289–294.

- MarwatSK, Fazal-Ur-rehman. Ricinus communis: Ethnomedicinal uses and pharmacological activities. Pak J Pharm Sci 2017; 30: 1815–1827.

- Momoh A.,OladunmoyeMK, Adebolu TT. Evaluation of the antimicrobial and phytochemical properties of oil from castor seeds ( Ricinus communis Linn). Bull Environ Pharmacol Life Sci 2012; 1: 21–27.

- Vieira C, Evangelista S, Cirillo R, et al. Effect ofricinoleicacid in acute and subchronic experimental models of inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2000; 9: 223–228.

- PabiśS, Kula J. Synthesis and bioactivity of (R)-ricinoleic acid derivatives: A review. Curr Med Chem 2016; 23: 4037–4056.

- Jena J, Gupta AK. Ricinuscommunislinn: A phytopharmacological review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2012; 4: 25–29.

- CIR expert panel. Final report on the safety assessment of Ricinuscommunis(castor) seed oil, hydrogenated castor oil, glyceryl ricinoleate, glyceryl ricinoleate SE, ricinoleic acid, potassium ricinoleate, sodium ricinoleate, zinc ricinoleate, cetyl ricinoleate, ethyl ric. Int J Toxicol 2006; 26: 31–77.

- DiPascualeMA, Goto E, Tseng SCG. Sequential changes of lipid tear film after the instillation of a single drop of a new emulsion eye drop in dry eye patients. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 783–791.

- KhanalS, Tomlinson A, Pearce EI, et al. Effect of an oil-in-water emulsion on the tear physiology of patients with mild to moderate dry eye. Cornea 2007; 26: 175–181.

- GotoE, Shimazaki J, Monden Y, et al. Low-concentration homogenized castor oil eye drops for noninflamed obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 2030–2035.

- MaïssaC, Guillon M, Simmons P, et al. Effect of castor oil emulsion eyedrops on tear film composition and stability. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2010; 33: 76–82.

- ScaffidiRC, Korb DR. Comparison of the efficacy of two lipid emulsion eyedrops in increasing tear film lipid layer thickness. Eye Contact Lens 2007; 33: 38–44.

- Craig JP, Wang MTM,GanesalingamK, et al. Randomised masked trial of the clinical safety and tolerability of MGO Manuka Honey eye cream for the management of blepharitis. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2017; 1: 1–9.

- Craig JP,PurslowC, Murphy PJ, et al. Effect of a liposomal spray on the pre-ocular tear film. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2010; 33: 83–87.

- Sung J, Wang MTM, Lee SH, et al. Randomized double-masked trial of eyelid cleansing treatments for blepharitis.OculSurf 2018; 16: 77–83.

- Muntz A, Sandford E, Claassen M, et al. Randomized trial of topical periocular castor oil treatment for blepharitis.OculSurf. Epub ahead of print 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.05.007.

*https://eyeonoptics.com.au/articles/archive/manuka-honey-cream-for-blepharitis/

Dr Alex Müntz is an optometrist and a post-doctoral research fellow in the OSL at the University of Auckland and was previously a clinical research scientist with the Centre for Ocular Research & Education at the University of Waterloo.

Associate Professor Jennifer Craig is head of the Ocular Surface Laboratory and a therapeutically qualified academic optometrist in the University of Auckland’s Department of Ophthalmology.