A Covid-19 experience: Watching a tsunami from afar

We are all spectators in life. I love sport and enjoy watching almost anything competitive. Through the years I’ve been fortunate enough to see live, the Ashes, Premier League football and the ‘Golden night’ of the 2012 Olympics. We are often amazed by the skill and passion on display but are just as consumed by the human tales which accompany great sporting achievement.

Over the last three months, I have been a spectator to something far more sinister, a contagious disease. As a doctor and as an ophthalmologist I’ve always taken an interest in outbreaks of disease from HIV, SARS and Ebola to Zika and now SARS-Cov-2. In January, my daily reading was about the outbreak of a novel pneumonia in Wuhan. As the days passed, my concern escalated in parallel to the exponential increase in infection and death rates. Initial hopes were that China and then Asia would contain what appeared to be a variety of SARS, just like Asia did in 2002-3.

Many things have happened since, as we approach the end of the four-week lockdown in New Zealand. Almost every person on the planet has had their personal and/or professional life altered in ways we never considered possible at the start of the year.

The shock of a true pandemic approaching is the first aspect that many of us had to deal with. Fear and anxiety can shadow our true personality when uncertainty occurs in our lives - I was certainly conscious about being over-zealous in some things.

At the beginning of February, I called a departmental meeting to reiterate the importance of hygiene measures, including hand hygiene and the sterilisation of equipment. As clinical lead, I knew I could take some comfort from our department’s ability to adhere to the highest levels of hygiene standards, including disposable tonometer heads and single use eye drops, to ensure the safety of the many elderly patients who attend our clinic.

On 6 February, I remember reading of the death of Dr Li Wenliang, the 34-year-old ophthalmologist who had raised the alarm in China about Covid-19 and the need to wear personal protective equipment (PPE). A sense of light headedness swept over me as the realisation came that this disease affects young and old, fit and unwell and even ophthalmologists!

Then came the start of many debates and discussions about what level of screening and precautions should be taken, at what time and for which people. This is where management and clinicians need to work together to allocate PPE appropriately. I have spoken with senior clinicians in the UK National Health Service where similar discussions were not so collaborative at the beginning of the pandemic; where some UK ophthalmologists were asked to stop wearing surgical masks at the slit lamp as this was not in line with policy!

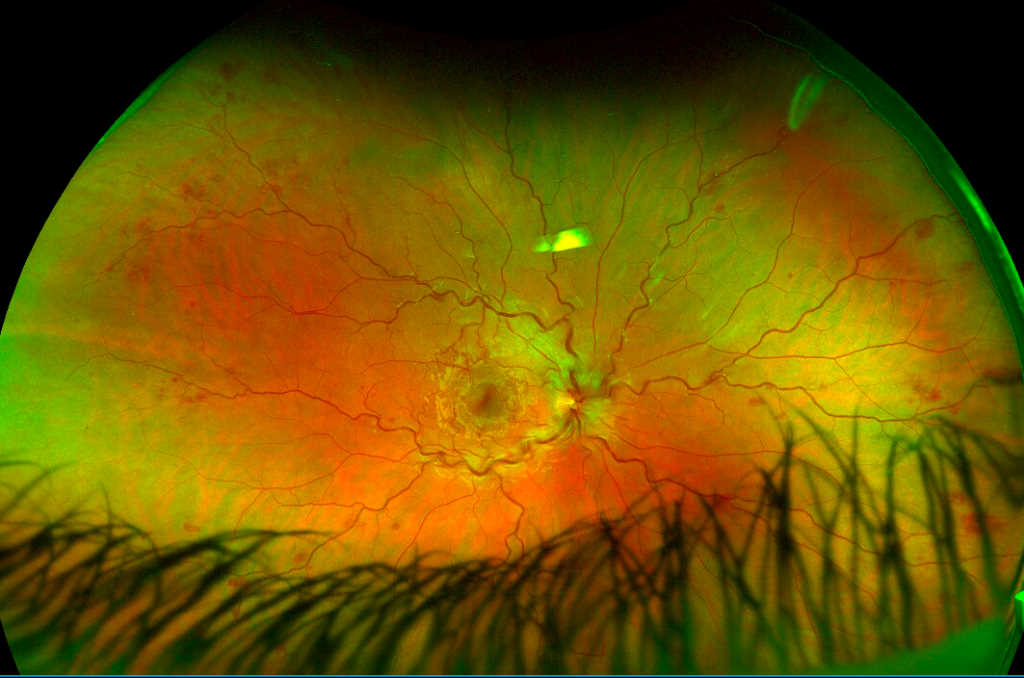

True, Covid-19 remains a relatively poorly understood disease and, at the start of a pandemic, policy can and does change on an almost daily basis. We don’t know whether the viral load at the time of contracting the disease is an important feature in severity. If it is, then all slit lamp users, both patient and professional, may be at increased risk of severe infection as droplet transmission will be high in such close proximity. We know three ophthalmologists in Wuhan died and many more healthcare professionals in all specialities have and will die over forthcoming months, partly because healthcare professionals are exposed to high numbers of more severe cases.

Even several weeks into the pandemic, and during the middle of New Zealand’s lockdown, the issue of wearing PPE for slit lamp examination remained in debate. Issues raised included what type of PPE - fluid resistant surgical mask versus filtering face piece respirator mask; for what type of procedure; for which patients; and when to change PPE - sessional use versus individual patient. Policy makers were forced to make decisions against the background of a global shortage of PPE and a lack of robust scientific evidence. On a personal note, I saw wearing a surgical mask as an extra safeguard to help protect my patients rather than to protect myself. With time, more evidence will enlighten us on this topic.

We do know that aerosol generating procedures (AGPs), like intubation of the airway, produces a high viral load and that means everyone in the room or operating theatre is at significant risk of contracting the disease unless wearing appropriate PPE. We also know that the nasopharynx is an area of very high viral particle load in infected patients and hence procedures such as dacryocystorhinostomy, which I often perform for nasolacrimal duct obstruction, are considered high risk. During the middle of the lockdown in New Zealand, the UK Royal College of Ophthalmologists deemed pars plana vitrectomy an AGP, so vitreoretinal surgeons had to adapt to using a microscope whilst wearing eye protection.

Eye units across the world have seen dramatic changes with all but essential vision threatening cases being managed by telemedicine, remote clinics and ophthalmic imaging. Slit lamp examinations are reserved for only the very necessary when all the above have failed. At the beginning of March my inbox was flooded by UK colleagues with pictures of how to make a homemade slit lamp breath shield from card or plastic. In our department, we were fortunate to have acquired professional, purpose-made perspex shields, which can be properly disinfected.

Healthcare systems around the world prepared and are still preparing for the arrival of wave upon wave of infected patents. Hospital responses include stopping all operating except true ophthalmic emergencies, consultants manning eye casualty to relieve juniors and discrete team working to reduce social interaction with colleagues.

A medical friend forced into self-isolation after having tested positive described to me the real fear he had of not knowing how he will respond to the disease. GP friends described a flood of patients with anxiety symptoms and disorders. An oncology friend described running clinics remotely where cancer patients with some of the most challenging conditions were managed online with altered treatment regimens to account for available, or the lack of, hospital beds.

Then there are all the personal impacts this disease has brought from failed businesses to missed family weddings, birthdays and even funerals, or the simple anxiety of having loved ones in isolation either within or outside the household unit.

Our hospital stopped all elective surgery in line with government guidelines. Performing my last operating list before the lockdown, I was warmed by the great satisfaction my role gives me of using my hands to heal people, the smiling faces of patients as we meet before surgery and the lovely responses the next day as vision is restored.

Over the 20 years I have been a doctor, I’ve spent 18 as an ophthalmologist. This role has been many things from fiercely competitive, tiring, enlightening, nauseating and fascinating to fulfilling and much more. Now, still in lockdown as I write this, I miss this more than ever.

New Zealand is fortunate. It has been given time: a most valuable and useful commodity in any pandemic - time to prepare, investigate, research, adapt and watch. If one was to watch a tsunami from a hillside, the wave out at sea would be unrecognisable. It is only as the wave builds height at the shoreline that we witness its devastating power.

Our hope remains that governments, district health boards, hospitals, healthcare professionals and essential services have cleared the shoreline of people and that we can now weather the effects of this pandemic better than most.

Dr Paul Baddeley is a consultant ophthalmologist and clinical lead at St George’s Eye Care in Christchurch, New Zealand. He studied clinical sciences at Cambridge University, medicine at Oxford University and completed his ophthalmology training in Wales. He has subspecialist skills in oculoplastic, lacrimal and orbital surgery and is an experienced surgical training advisor.