Street simulations to combat falls

By 2050, the number of people over 65 will have tripled worldwide and around one in three living at home will have at least one fall per year, according to the UK’s National Health Service. At the Vision Institute in Paris, Professor José-Alain Sahel and Emmanuel Gutmann have developed a unique platform called StreetLab to reproduce naturalistic situations to assess and help improve the autonomy and mobility of visually impaired people and seniors. Dr Angelo Arleo, winner of the 2020 Silmo Academy Award and head of the Aging in Vision and Action laboratory, uses StreetLab for gathering and evaluating detailed mobility-related data from subjects in a controlled environment. We sent Drew Jones to ask Dr Arleo about his research and what the implications are for eyecare professionals.

Why did you enter the 2020 Silmo Academy awards?

We have about 30 people working here at the Aging in Vision and Action Lab, and they knew about the awards, so they asked me, ‘Why are we not applying? It’s a very good thing, selective and prestigious’. I’m very glad I listened to some of the younger voices on the team!

Thirty people, all working on StreetLab?

Since about 70% of the work carried out in my lab is about mobility and spatial orientation, we largely rely on the StreetLab platforms to test our hypotheses about physiological and/or pathological visuo-cognitive ageing. These naturalistic experiments are not easy to run - hence the large number of researchers involved in manipulating the StreetLab scenery and monitoring the subject - but they allow the action-perception loop to be studied in realistic yet controlled conditions.

Do you also use virtual reality (VR) headsets?

Absolutely, yes. We do use VR with a virtual version of the StreetLab platform. It’s much faster and easier to run highly controlled spatial navigation experiments. So we use VR a lot, especially when we need to run experiments that require us to dynamically switch between different environments. The only difficulty with the VR approach is that participants must explore the virtual space by actually moving their body in the physical space, which requires quite a large empty space… which is not easy to find in Paris!

Does VR present difficulties if the sounds don’t match what the subject sees in the virtual world?

We try to provide auditory feedback to match the visual immersion, but there are still problems when you’re in this different world – the multisensory integration somehow gets disrupted. It’s like the brain downplays the information it gets from your feet and your legs and concentrates on vision. So, that’s very important to be aware of.

There are so many factors, such as cataracts, eye diseases, muscle atrophy, diminished neuroplasticity and inner-ear issues, that can cause older people to fall – how do you unravel it all?

That’s exactly the point. When we started the research programme six years ago, we immediately realised the complexity of the project and the fact that a holistic approach had to be taken. So we started to identify all the phenotyping tests to ensure there were as few biases as possible in the interpretation of our results, and to use this wealth of information to understand why individuals of the same age and same clinical state would respond differently. For example, if you have two people of the same age and similar clinical state but one of them has depression, the depressed subject is more likely to experience perceptual as well as cognitive declines. This approach made us put the individual’s perspective at the centre of our reasoning, as opposed to treating each participant as average.

Dr Angelo Arleo, winner of the 2020 Silmo Academy Award and head of the Aging in Vision and Action laboratory in Paris

The StreetLab platform allows many environmental parameters to be controlled very accurately, such as lighting, temperature and 3D sound. Our next challenge is to run mobility and spatial navigation experiments in the real world. We recently started a project with the SNCF (the French national railway system) in Gare de Lyon, one of the biggest rail stations in Paris. In these less controlled conditions, we can still monitor where the subject’s eyes are looking and use accelerometers to reconstruct how their body moves in space. We just started the pilot and it’s very exciting.

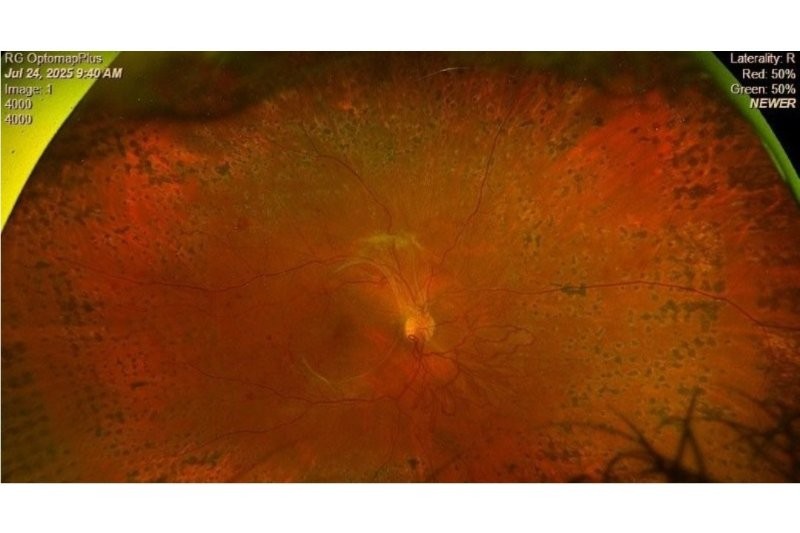

Complementing our spatial navigation experiments, we also perform a lot of clinical screening to characterise each individual of our ‘Silversight’ cohort as much as possible. The participants of the cohort have been followed up for almost seven years and we’re currently trying to identify cross-causal relationships between very different and heterogeneous measures, such as high-resolution retina imaging (adaptive optics, optical coherence tomography), brain imaging (functional magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography or EEG) and behavioural markers (eye movements, postural and gait control).

Past studies have shown how drastically stair geometry affects fall frequency for different people. Will your research impact urban and home design, and perhaps even lens design?

Navigating an environment is a multisensory process and vision is an important part of that. We are combining vision and other sensory information and that usually works well in young people. However, the way this multimodal information is processed declines with age and older people become more vision dependent. They also tend to lose the stereo vision that allows them to estimate small differences in depth. So one of the ideas of this project is to somehow rebalance the subject’s visual and other sensory cues to help older people become less prone to falls.

When will you be releasing the results of this study?

We started in 2014, so we have now collected a large amount of data. Besides the already published papers, we have at least 10 papers currently under review. There are some new developments in terms of pathological visual ageing and visual restoration, as well as some novel results obtained using non-invasive neuroimaging techniques (such as EEG) to record the brain activity during mobility and spatial navigation tasks. The first of these should be published in the next few weeks, which we’re very excited about.

Drew Jones is a freelance writer and sub-editor, with family links to New Zealand. Currently based in Ireland, he is the newest member of the eyeonoptics team.