Children’s eye chart upgraded

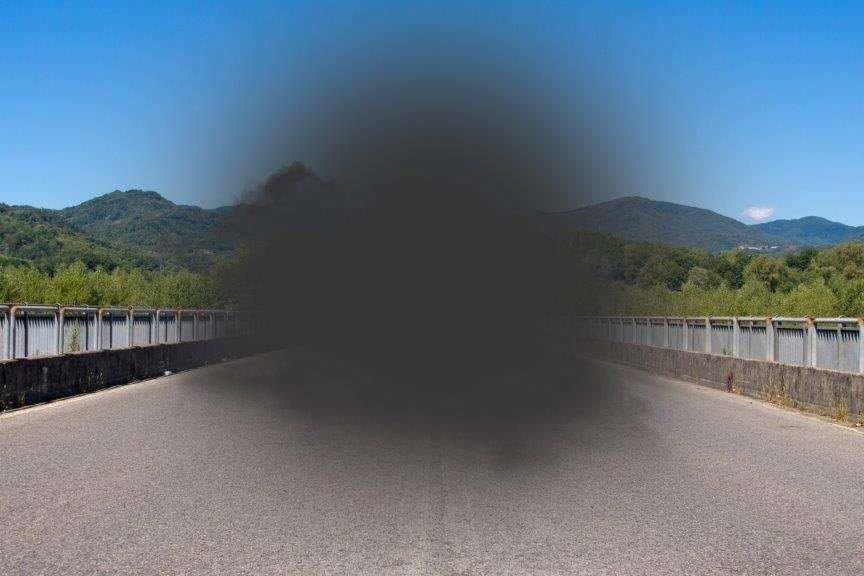

A series of new symbols for testing visual acuity in children is more reliable than those used in current charts, claim the Auckland researchers who developed them.

Current eye charts have several shortcomings, including some symbols being easier to identify than others, said Professor Steven Dakin, head of the University of Auckland’s School of Optometry and Vision Science (SOVS).

SOVS researcher Dr Lisa Hamm, who led the design and testing of the new eye chart symbols (optotypes), over the past four years said she decided to develop a new, 10-item symbol set for children because a larger set reduced the potential for children to guess correctly. “We wanted 10 recognisable images, with no internal features or open ends, where no two items were too similar that they become more difficult than the others.”

It was surprisingly difficult to design a set of principled optotypes, she added, for example ensuring two asymmetrical items, such as the car and the duck, were no easier to identify than the rest. “We found that if they faced the same way it offset their uniqueness.”

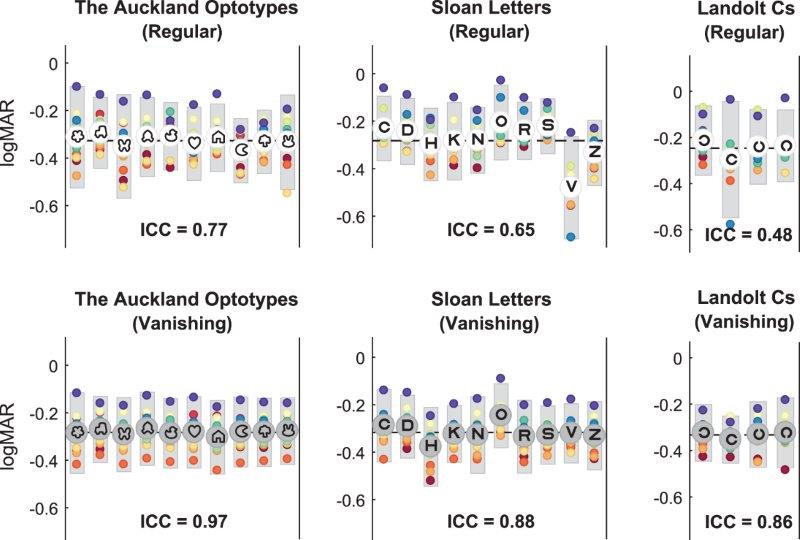

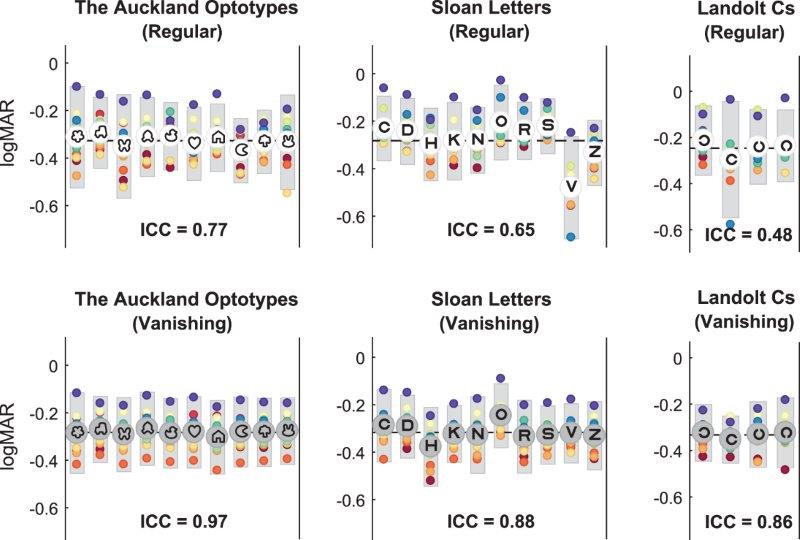

The intraclass correlation (ICC) value denotes the proportion of variance attributable to differences between subjects. Higher ICC values demonstrate more consistent acuity estimates between optotypes

Dr Hamm iteratively modified the set until she got symbols that were similar to one another - evaluated using image processing – but that remained visually distinctive, said Prof Dakin.

For testing, the team collaborated with low decile schools in New Zealand and Tonga. Accurate visual acuity screening relied on factors over and above well-designed symbols, stressed Dr Hamm. “Ethnicity, age and experience all contribute to perceptions of the symbols. For instance, when using the optotypes in Tonga, children tended to identify the rocket optotype as a campfire.”

For the New Zealand study, each child was tested with the current standard Parr preschool screening booklet and with the new optotypes and given a full eye exam. The new eye chart was more accurate than the standard Parr test. The Parr test was good at catching children with amblyopia, but failed too many visually normal children, said Prof Dakin.

The new optotypes were also trialled on children in the Growing Up in New Zealand study. Trained screeners delivered an acuity test on a tablet computer which had been set up to film the children using its webcam. Children wore special markers on the patch covering one eye, allowing the researchers to measure the distance between the child’s eye and the new optotypes during testing.

“Children move a lot!” said Dr Hamm. “At 40cm, 18% gained a line by leaning forward a little and even at 150cm, 8% achieved the same improvement.”

Taking postural variation into account was a new source of variability in testing of children, that has a big impact on results, said Prof Dakin. “The set we’ve developed is, I would argue, superior to the commonly-used Sloan letters in every way.”

SOVS is making the optotypes available to researchers around the world, including Moorfields Eye Hospital, to gain additional feedback, which should speed up and improve the ‘norming’ process and make the symbols even more effective, said Dr Hamm. The new tests should be available to clinicians, free of charge, in the next few years.

The optotypes can be accessed at https://github.com/dakinlab/OpenOptotypes