CASE STUDY: periorbital cellulitis or worse?

A 6-year-old female was referred by her GP with the chief complaint being right, upper lid swelling. Prior to that, there was a history of sinusitis with coryzal symptoms for a week. She was initially treated by her GP with oral antibiotics for 10 days and there was no improvement at all.

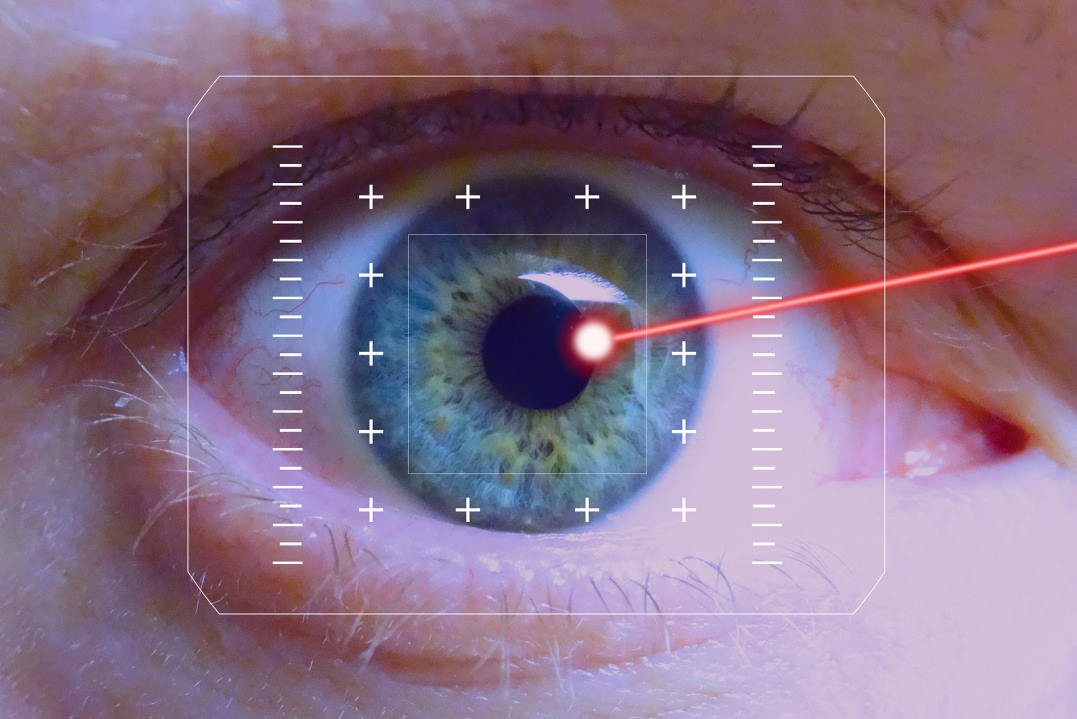

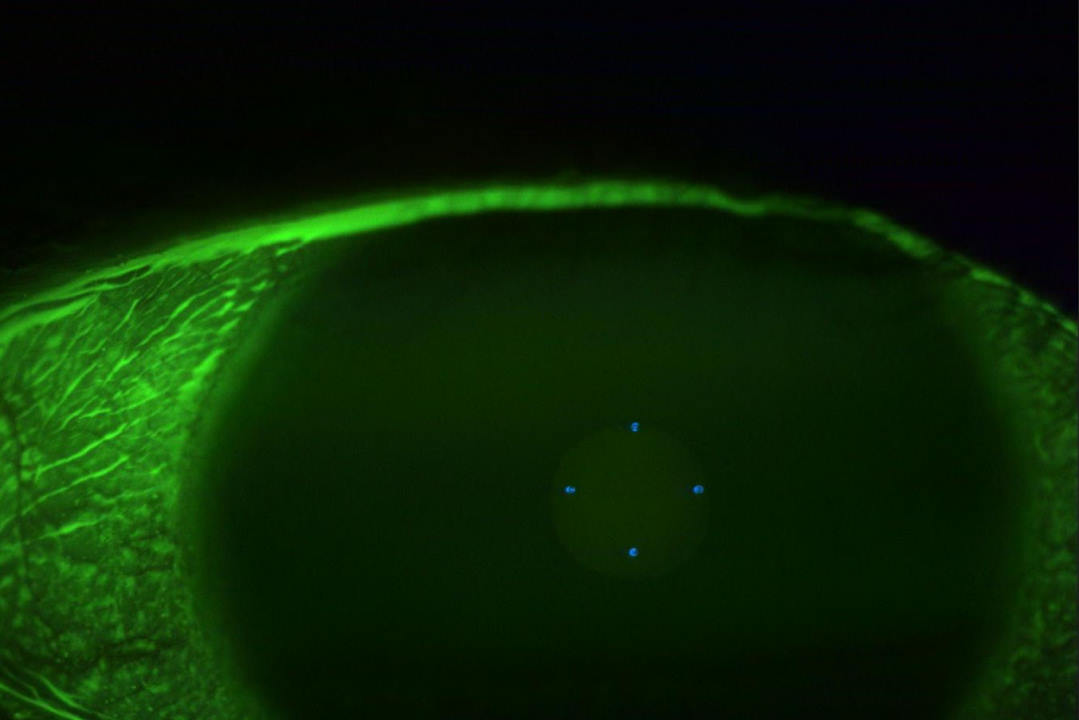

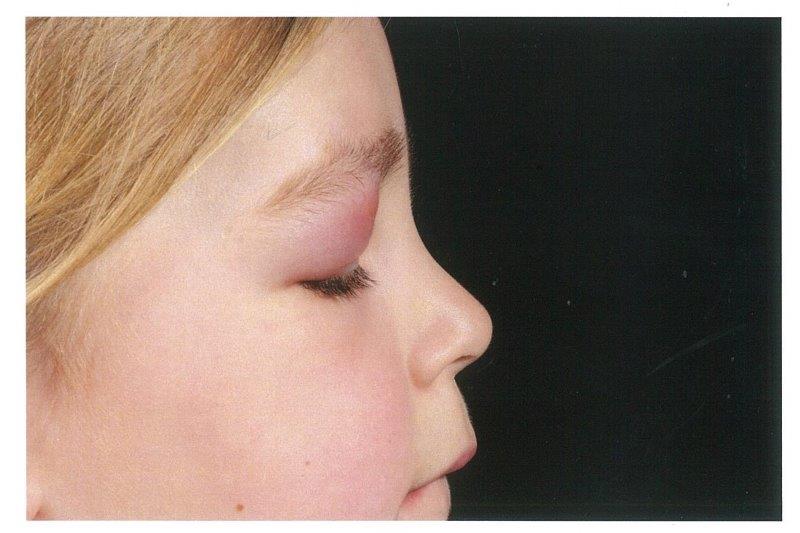

The patient then presented acutely one month later with general right, upper lid swelling, which was red, indurated and tender (Fig 1 and 2). She was not systemically unwell. She had no ocular history and there was no family history of ocular disorders. On examination, her right, upper lid was swollen, red, tender and indurated. Her best corrected visual acuity was 6/9+1 in the right eye and 6/9-2 in the left eye. All other aspects of the examination were normal.

Fig 2.

Diagnosis

Initially, the case was treated as a viral lid swelling. However, after rapid worsening of the symptoms and depression of the lobe, the preferred diagnosis became upper-lid periorbital cellulitis. Differentials included orbital cellulitis, abscess and other causes lymphoma. IV antibiotics were commenced and the patient was referred for CT orbit to rule out cellulitis/retro-orbital abscess.

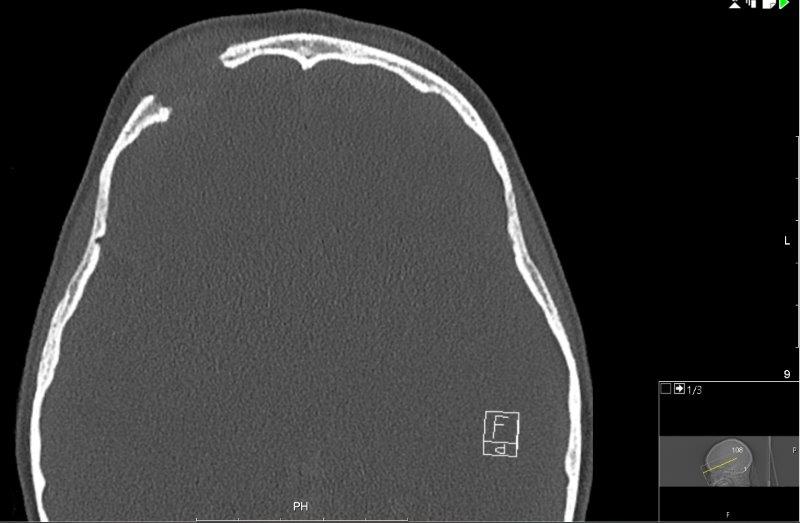

The CT scan (Fig 3) showed a destructive lesion superior to the right globe with destruction of right frontal bone and also the supra-orbital ridge. There was a solid material of intermediate density with well-defined margins bulging into the eyelid. Bony views showed a very well defined ‘punched out’ lesion well away from the sinuses. Further evaluation with an MRI was suggested to characterise the lesion.

Fig 3.

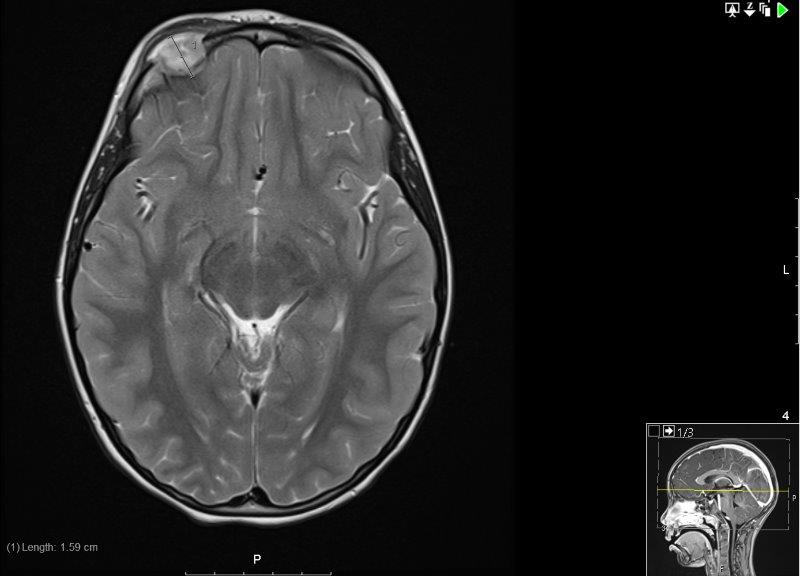

An MRI scan of the orbit, along with a whole-body MRI STIR (to screen for other lytic lesions) were conducted. The MRI demonstrated the soft tissue mass mushrooming through a bony defect with peripheral enhancement, and associated pachymeningeal and leptomeningeal enhancement where the mass bulged against the right frontal lobe (Fig 4). The whole-body STIR showed multiple bilateral abnormalities in the tarsal bones and also the cuboids, which were likely to be bony abnormalities reflecting the patient’s interest in gymnastics.

Fig 4.

Following these investigations and further discussion with the neurosurgical and paediatric teams, the revised diagnosis was Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). As part of the initial work-up of this new diagnosis, a skeletal survey was done with a full-body x-ray, which showed only a solitary bony lesion in the right supraorbital region.

Treatment

The treatment of LCH depends on the classification of the lesion’s risk to the central nervous system.

In the case of this patient, the dural and meningeal enhancement and the location of this lesion rendered it a CNS risk lesion. The patient was enrolled onto the LCH4 clinical trial. Her treatment included prednisone, vinblastine and mercaptopurine (Stratum 1 interim course 1, followed by interim course 2). She was randomised to be in the longer treatment group (12 months versus six). After the end of treatment, the surveillance plan was as follows:

- In the first year following the end of treatment: clinical review plus full blood count, ESR, liver function tests (LFTs), kidney function tests plus urine osmolality every three months; skull x-ray every three months; MRI (head) to be carried out only if there is clinical suspicion of recurrence

- Second to fifth year: clinical review plus full blood count, ESR, LFTs, renal function and urine osmolality every six months, with imaging only if clinical suspicion of recurrence

Comment

LCH, previously known as histiocytosis X, is a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells which resemble tissue macrophages, juxtaposed against a backdrop of inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils, that may manifest as a unisystem or multisystem disease. In 55% of patients, the disease is limited to one organ system (eg. bone), while the remainder presents with multisystem disease.

Three clinical forms of LCH have been identified: localised LCH (eosinophilic granuloma), Hand-Schuller-Christian (HSC) disease and Letterer-Siwe disease. Eosinophilic granuloma is the most frequent form of LCH, though involvement of the orbit is relatively uncommon. If present, it is usually characterised by osteolytic bone lesions in the superotemporal quadrant of the orbit that are unilateral and unifocal. Patients will then present with progressive upper eyelid swelling, erythema and tenderness which is localised. Bone destruction with soft tissue expansion is seen in almost all causes of eosinophilic granuloma because the Langerhans cells cause osteolysis through elaboration of interleukin-1 and prostaglandin. HSC is a multifocal variant of eosinophilic granuloma whereas the Letterer-Siwe disease is acute disseminated LCH.

References

- Herwig MC, Wojno T, Zhang Q, Grossniklaus HE. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis of the Orbit: Five Clinicopathologic Cases and Review of the Literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(4):330-340.

- Lian C, Lu Y, Shen S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: a case report and review of the literature. Oncotarget. 2016;7(14):18678-18683.

Aqeeda Singh is a fifth-year medical student at Otago University in Dunedin with a special interest in ophthalmology and ophthalmology research.

Dr Sheng Chiong Hong is a training ophthalmology registrar based in Dunedin and co-founder of ophthalmic and AI tech social enterprises MedicMind and oDocs Eye Care.