Eye melanomas: a local and global perspective

Melanoma is the most common primary eye malignancy in adults and the eye is the second most common site for melanoma following the skin1. Eye melanomas are best described according to the anatomical location within the eye, as they differ in clinical presentation and behaviour, epidemiology, risk factors, genetic involvement, management, metastatic potential and prognosis. There are two major subtypes: uveal melanoma (comprising iris, ciliary body and choroidal melanoma) and conjunctival melanoma. Ciliary body and choroidal melanoma are frequently described together, collectively referred to as posterior uveal melanoma, while iris melanoma is described separately due to recognition of its more favourable prognosis compared with other eye melanomas.

Here, we summarise the results of local research on the epidemiology of uveal and conjunctival melanomas as well as the treatment modalities available within Aotearoa New Zealand.

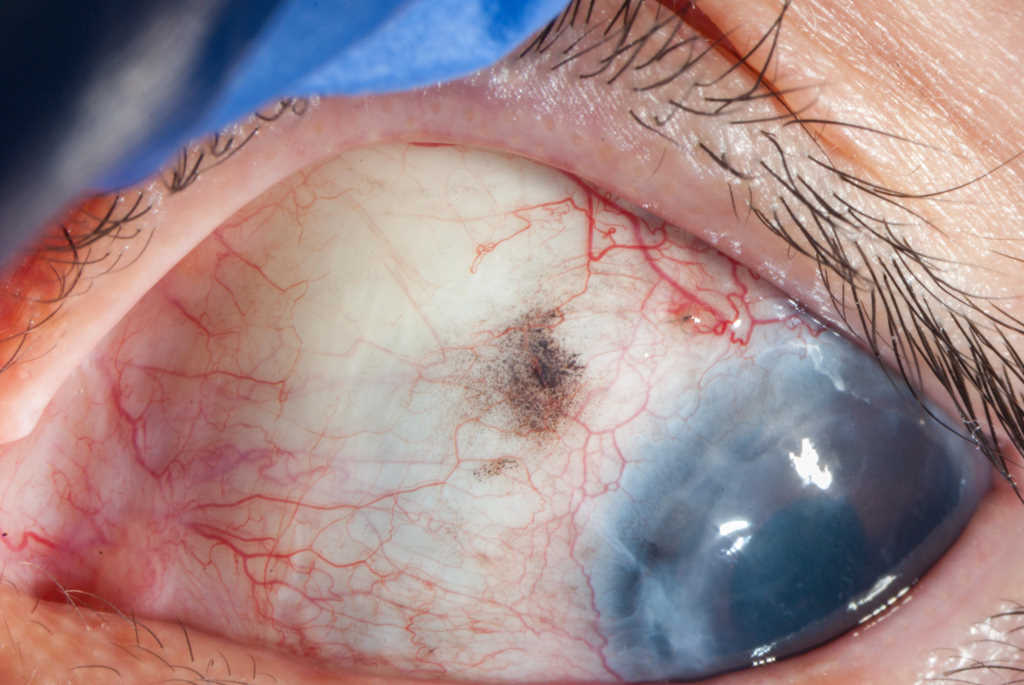

Conjunctival melanoma

Conjunctival melanomas (Fig 1) account for 10% of all eye melanomas and, alongside squamous cell carcinomas, are the most frequently occurring malignant conjunctival lesions. They can arise from pre-existing primary acquired melanosis (PAM), naevus or de novo (uncertain origin). The limbal conjunctiva is the most common site for development, followed by the bulbar conjunctiva, diffuse, palpebral conjunctiva, corneally displaced and caruncle.

Fig 1. Conjunctival melanoma in a patient’s right eye showing involvement of (A) superior limbus, (B) inferior limbus, (C) inferior fornix and (D) nasal bulbar conjunctiva

Treatment is typically excision biopsy with cryotherapy and adjuvant local chemotherapy based on histopathology. Unfortunately, the chance of local recurrence is high, occurring in two-thirds of patients, emphasising the importance of ongoing, regular eye examinations following treatment. Metastasis occurs in approximately 25% of patients, principally through the lymphatic system, typically affecting regional lymph nodes but may also involve distant organs including the lungs, brain, liver and bones. Melanoma-related mortality occurs in approximately 10% of patients at five years, thus long-term systemic surveillance is important.

In studies conducted in the late 1900s, the global incidence of conjunctival melanoma ranged from 0.1 to 0.9 cases per million population per year, with increasing incidence trends in tandem with the increasing incidence of cutaneous melanoma2, suggesting an association with ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. Indeed, conjunctival melanoma has been demonstrated to harbour UV-associated genetic mutations, which further supports the observed trends. To date, New Zealand has the highest global burden of skin melanoma3 and the highest incidence of ocular surface squamous neoplasia4, but the epidemiology of conjunctival melanoma had been unknown until recently. In our 2023 study, the incidence of conjunctival melanoma after the turn of the millennium (2000-2020) was 0.6 cases per million population per year, with no increasing trend observed over 21 years5. These results indicate no increased burden of conjunctival melanoma within New Zealand. We note this coincided with a period of increasing evidence of sun exposure as a risk factor for skin melanoma, triggering sun protection measures that we theorise may have indirectly protected high-risk individuals from developing conjunctival melanoma5. Further studies of pre-2000 data may be useful to understand any significant longitudinal trends in the country’s burden of conjunctival melanoma.

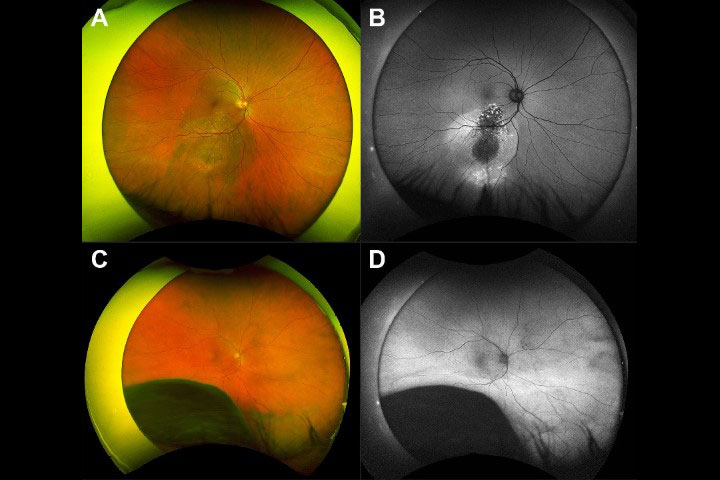

Posterior uveal melanoma

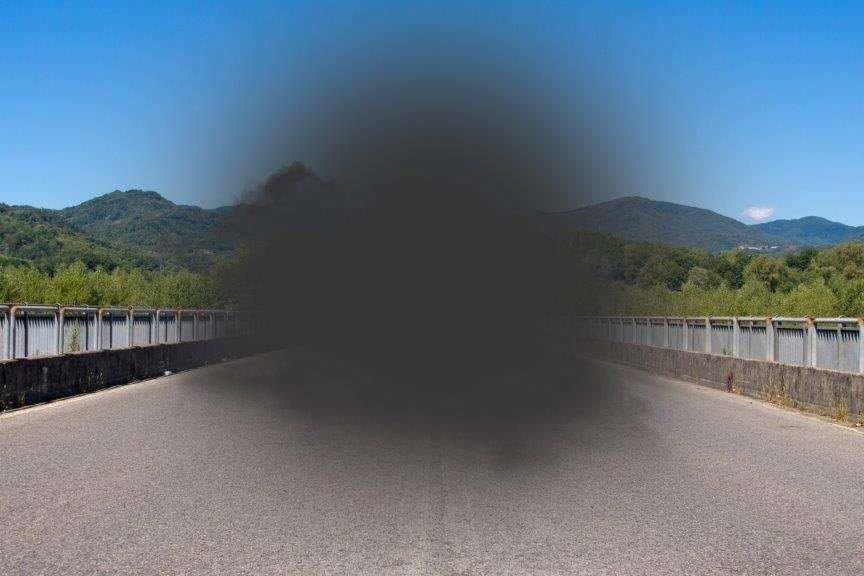

Posterior uveal melanoma (arising from the choroid and ciliary body, Fig 2, top) makes up the majority of uveal melanomas (96%)1. They are not only sight threatening but have poor survival prognosis, as there is currently no successful systemic treatment for metastases. Up to 50% of all patients diagnosed with posterior uveal melanoma go on to develop metastasis in their lifetime, predominantly spreading through the blood to the liver, with median survival being approximately 12 months from detection of metastasis1. Most posterior uveal melanomas develop silently and are often picked up during routine eye examinations with eye clinicians. Notably, in unpublished local data, 43% of tumours reviewed in the ocular oncology clinic in Auckland in 2022 were initially detected by optometrists. The most common presenting symptoms are decreased/blurred vision, visual field defect, floaters and light flashes.

Treatment of posterior uveal melanoma is dependent on tumour size and patient preference, and is broadly categorised into either enucleation (all large tumours) or eye-sparing procedures (small to medium-sized tumours). If enucleation is pursued, this can be carried out in the patient’s base hospital and prosthetic eye fitting can be considered after six weeks. Eye-sparing treatment modalities available in New Zealand include plaque brachytherapy, currently provided at Greenlane Hospital in Auckland (and at Christchurch Hospital prior to 20046) or stereotactic radiotherapy, provided in Dunedin Hospital7.

Another eye-sparing treatment is proton beam radiotherapy. However, this treatment is presently carried out for New Zealand patients at the Royal Liverpool University, UK. Fortunately, the Southern Hemisphere’s first clinically dedicated proton beam therapy centre is being installed at the Australian Bragg Centre in Adelaide and will be available for treatment in 2025.

Following successful treatment, long-term systemic surveillance for metastases is warranted. This can be pursued in conjunction with an oncologist, with six-monthly liver function tests and liver ultrasound, or more extensive scanning, depending on clinical indication.

The incidence of uveal melanoma globally ranges from 5 to 11 cases per million population per year. The incidence of histologically confirmed uveal melanoma from 2000-2020 was six cases per million New Zealand population per year, with at least a further third of cases diagnosed clinically and treated without tumour verification (eye-sparing treatments)8. Our studies confirm global observations that this disease predominantly affects European populations, with a typical phenotype of fair skin and light iris colour; however, notably, 4% of our patients with uveal melanoma identified as Māori. Prior to this study, there was only one case of choroidal melanoma affecting Māori reported in the literature9.

Surprisingly, we observed the age at diagnosis in ethnic groups with more pigmented skin and iris colour (Māori, Asians and Pacific Peoples) was younger by a decade than in European ethnicities. Elsewhere, lower age at presentation has also been noted in Asian, Black, Pacific and Hispanic populations. Genetic analysis confirms Māori have origins in Southeast Asia, Melanesia and Polynesia10. Given this ancestry, it is possible that the earlier age at diagnosis observed in our Māori population may be related to underlying genetic similarities to the Asian and Pacific cohorts. The overall infrequency of uveal melanoma in Māori, Asian and Pacific Island ethnicities may be related to increased skin and eye pigmentation as a protective factor, but occupation, cultural, or environmental factors may also affect their earlier presentation. Given the rarity of these tumours, further multicentre studies are warranted to uncover underlying genetic differences in uveal melanoma occurring in different ethnicities.

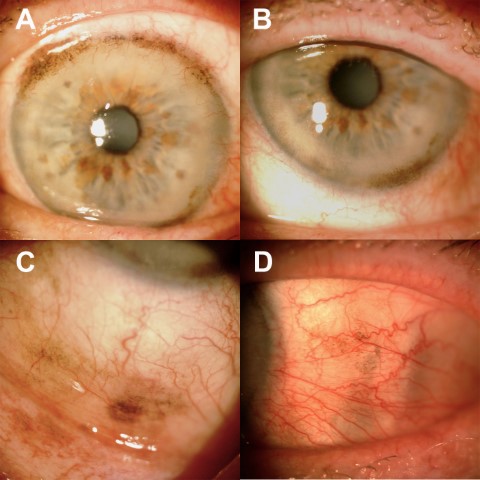

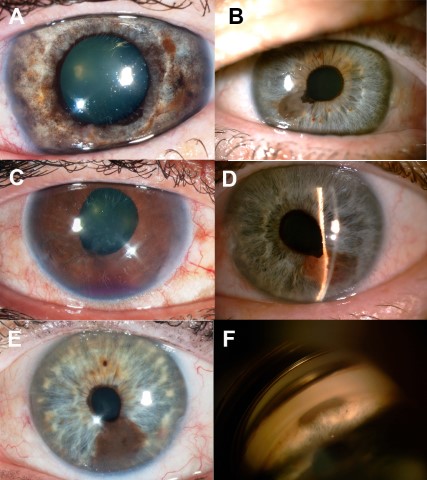

Iris melanoma

Iris melanomas (Fig 3) represent approximately 4% of all uveal melanomas. The incidence is approximately 1 case per million population per year, with New Zealand having the highest published incidence globally11. They are generally found on routine eye examinations in asymptomatic patients and detected 10-20 years earlier than posterior uveal melanomas, owing to their position in the visible iris12. This may explain the low risk of metastasis and death at 10 years – 9% and 3%, respectively1. A particular risk factor for iris melanoma is pre-existing iris naevus, with approximately 5% of naevi shown to transform into melanoma at five years. Risk factors for malignant transformation can be summarised with the ‘ABCDEF’ guide indicating the following:

A – young Age (40 years or younger)

B – Blood

C – Clock hour inferior

D – Diffuse, flat tumour

E – Ectropion uveae

F – Feathery margins1

Fig 3. Various presentations and malignant features of biopsy-confirmed iris melanomas in Aotearoa. (A) Diffuse iris melanoma presenting as iris heterochromia. (B) Inferior pigmented lesion with ectropion uveae. (C) Blood in the anterior chamber causing elevated IOPs. (D) Raised, vascular lesion with mixed pigmentation. (E) Large inferior iris lesion with feathery margins. (F) Gonioscopy of iris lesion demonstrating angle involvement

In our high-UV climate, local studies have demonstrated the majority of our pigmented iris tumours were tumour category T1 (local tumours with no invasion of surrounding structures) and, in our quaternary centre in Auckland, most iris tumours are treated using minimal iris touch excision (MITE)13, a novel surgical technique developed in our centre to reduce the risk of tumour seeding within the anterior chamber during suturing)14. Consequently, many of these tumours are amenable to local resection. If the resected margins demonstrate tumour involvement, further treatment with radiotherapy or, rarely, enucleation, may be pursued.

In many centres globally, iris melanomas are increasingly being treated with radiotherapy (plaque or proton beam radiotherapy). Although an effective approach to iris melanoma, the side effects are not inconsequential as eyes often suffer significant, sometimes permanent, radiotherapy-related side effects including vision loss, limbal stem cell compromise, keratitis, cataracts and glaucoma, typically requiring further treatment.

Iris defects post tumour excision often cause significant glare and, for some patients, significant cosmetic concerns. The iris defect can be reconstructed surgically using several techniques including pupilloplasty, iris segments, or insertion of an endocapsular artificial iris15. The latter has been shown to provide good visual outcomes and high patient satisfaction in our population16.

Summary

The burden of eye melanoma in New Zealand is substantial, with significant impact on patients’ vision, visual rehabilitation and longevity. Early detection is key for the patient’s best visual and survival prognosis; however, this may often be difficult as symptoms prompting presentation to an eye clinician typically occur when the malignancy is more advanced.

Following treatment, long-term surveillance with multidisciplinary involvement (often in tandem with the patient’s general practitioner or oncologist) is required to detect recurrence or systemic metastasis.

References

1. Kaliki S, Shields C. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye (Basingstoke). 2017;31(2):241-257.

2. Virgili G, Parravano M, Gatta G, et al. Incidence and survival of patients with conjunctival melanoma in Europe. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(6):601-608.

3. Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(5):495-503.

4. Hossain R, McKelvie J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia in New Zealand: a ten-year review of incidence in the Waikato region. Eye (Lond). 2022;36(8):1567-1570.

5. Lim J, Misra S, Gokul A, Hadden P, Cavadino A, McGhee CNJ. Conjunctival Melanoma in Aotearoa-New Zealand: A 21-year analysis of incidence and survival. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2023;12(3):273-278.

6. Stack R, Franzco M, Abdelaal A, Hidajat R, Clemett R. New Zealand experience of I 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:490-494.

7. Haji Mohd Yasin N Bin, Gray A, Bevin T, Kelly L, Molteno A. Choroidal melanoma treated with stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy and prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab: The Dunedin Hospital experience. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2016;60(6):756-763.

8. Lim J, Gokul A, Misra S, Hadden P, Cavadino A, McGhee C. The burden of histologically confirmed uveal melanoma in New Zealand: A 21-year review of the National Cancer Registry. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol. 2023;12(in print).

9. Elder M, Dempster A, Sabiston D, Clemett R. Primary choroidal malignant melanoma occurring in a New Zealand Maori. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1998;26(1):41-42.

10. Underhill P, Passarino G, Lin A, et al. Maori origins, Y-chromosome haplotypes and implications for human history in the Pacific. Hum Mutat. 2001;17(4):271-280.

11. Michalova K, Clemett R, Dempster A, Evans J, Allardyce R. Iris melanomas: Are they more frequent in New Zealand? Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(1):4-5.

12. Allen N, Misra S, McGhee C, Crawford A. Case Series: Different presentations of iris melanoma-potential masquerade of benign and malignant. Optom Vis Sci. 2022;99(3):298-302.

13. Meyer J, Krishnan T, McGhee C. Minimal iris touch excision: a novel surgical technique for local excision of iris melanoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(3):298-299.

14. Rapata M, Zhang J, Cunningham W, Hadden P, Patel D, McGhee C. Iris melanocytic tumours in New Zealand/Aotearoa: presentation, management and outcome in a high UV exposure environment. Eye 2022. Published online March 25, 2022:1-8.

15. Crawford A, Freundlich S, Zhang J, John McGhee C. Iris reconstruction: a perspective on the modern surgical armamentarium. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2021;14(2):69-73.

16. Crawford A, Freundlich S, Lim J, McGhee C. Endocapsular artificial iris implantation for iris defects: reducing symptoms, restoring visual function and improving cosmesis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;50(5):490-499.

Dr Joevy Lim is a Health Research Council clinical research fellow in the final year of her PhD research on ocular melanoma in Aotearoa and will be commencing her RANZCO training in 2024. She would like to take this opportunity to thank all parties who have participated, supported, encouraged and provided feedback on the research she has carried out in the past three years; with special thanks to her supervisors and advisors, Prof McGhee and Drs Stuti Misra, Akilesh Gokul, Peter Hadden and Alexandra Crawford, and New Zealand's optometrists and their patients.

Professor Charles McGhee heads the Department of Ophthalmology and is director of the New Zealand National Eye Centre at the University of Auckland. His interests include keratoconus, corneal diseases and corneal transplantation, complex cataract and anterior segment trauma, and complex anterior segment pathology, including iris and conjunctival melanoma and other rare anterior segment tumours, for which he receives nationwide referrals.