Neovascular glaucoma

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is a glaucoma that develops secondary to ischaemic retinal vascular disease. It is characterised by anterior segment neovascularisation leading to an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) and glaucomatous optic neuropathy. If not diagnosed and treated promptly, NVG can cause severe, permanent loss of vision and eye pain.

Case report

A 73-year-old male presented to his optometrist with a three-week history of blurred vision in his right eye. He reported no associated ocular or systemic symptoms and no past ocular or medical history of note.

His right eye’s best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6/12 and his left 6/6. IOP’s were 17mmHg in the right eye and 21mmHg in the left eye. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Posterior segment exam demonstrated scattered retinal haemorrhages at the posterior pole of the right eye. The left posterior segment was noted to be normal.

The patient was referred semi-urgently to the eye clinic the following week but did not attend his appointment. Two weeks later, the patient presented to the acute eye clinic with a one-day history of rapid loss of vision, photophobia and redness affecting the right eye.

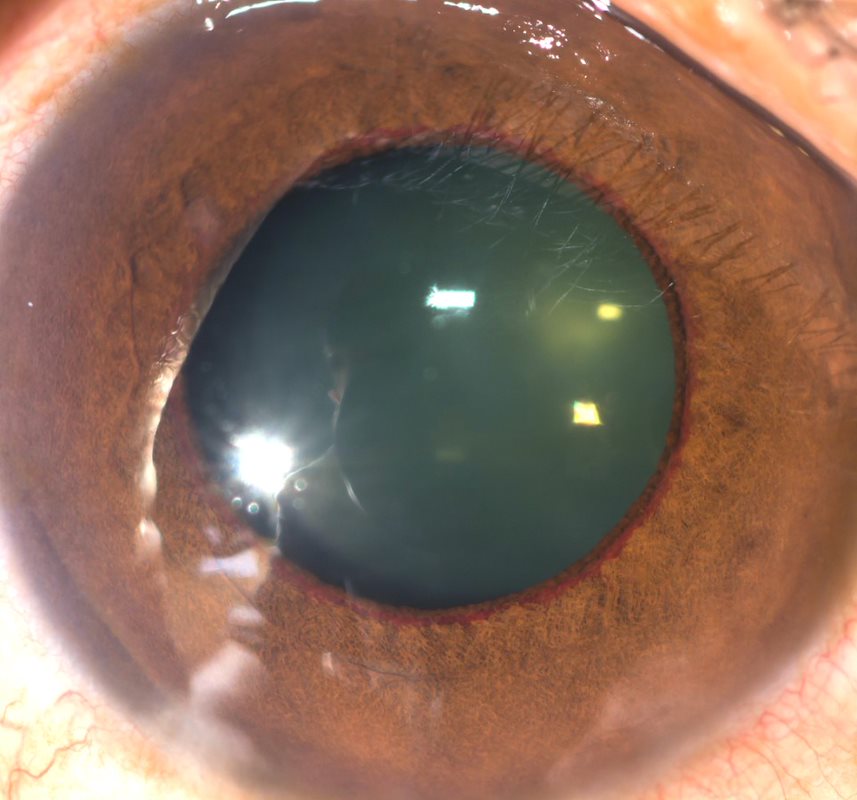

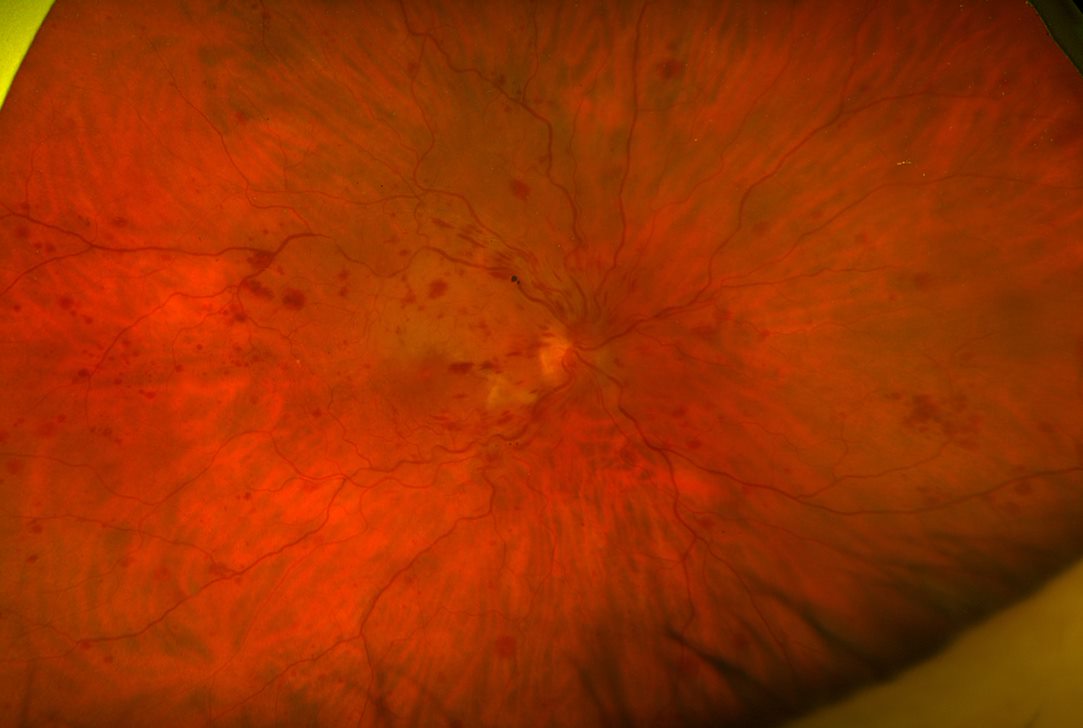

His right BCVA was now counting fingers (CF) and the left 6/6. His IOPs were 46mmHg in his right eye and 22mmHg in his left. In the right eye, new vessels on the iris (NVI) (Fig 1) and in the drainage angle (NVA) were identified. Posterior segment examination demonstrated retinal haemorrhages and venous tortuosity consistent with a central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) (Fig 2). Additional findings on macula ocular coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrated an epiretinal membrane and cystoid macula oedema (CMO).

Fig 1. Anterior segment image showing iris neovascularisation at pupil margin

Fig 2. Fundus image demonstrating signs consistent with Right CRVO

A diagnosis of right NVG secondary to a CRVO was made. The patient was given oral acetazolamide (Diamox) 500mg immediately together with one drop of apraclonidine (Iopidine), brinzolamide (Azopt) and timolol 0.5%. He had an intravitreal injection of Avastin after an anterior chamber tap was performed. The next day, the right BCVA remained CF and the left 6/6. The IOPs were 29mmHg right eye and 11mmHG left eye. Panretinal photocoagulation of the right retina was performed and the patient discharged home on Diamox 250mg three times a day (TDS), along with Combigan twice daily and Predforte six times a day to the right eye.

One week later, the right BCVA was still CF and the left 6/6. The IOPs were 13mmHG right eye and 14mmHg left eye. The anterior chamber (AC) was deep and quiet and the NVI/NVA had resolved. The patient was asked to continue on his current treatment and closely monitored over the following weeks.

Causes

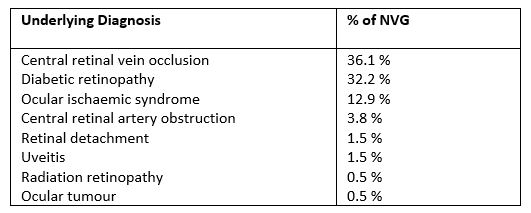

NVG can be caused by any condition that leads to retinal ischaemia, as presented in Table 11-3. CRVO is considered the most common underlying cause with NVG typically developing around three months after onset. Hence the term, 100-day glaucoma. It has been reported that 16% of CRVO and nearly 30% of ischaemic CRVO will develop NVG within six months4,5.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the next most common cause of NVG and can be a devastating cause of loss of vision in diabetic patients. PDR is by far the most common cause of bilateral NVG2. Ocular ischaemic syndrome (OIS) due to carotid artery occlusion is another common cause of NVG and needs to be carefully considered in the absence of a CRVO or PDR1-3.

Table 1. Causes of NVG

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of NVG is multifactorial and involves a cascading series of events. Retinal hypoxia leads to the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor and multiple other pro-angiogenic proteins involved in the formation of new blood vessels6. These new blood vessels develop in the anterior chamber as NVI and NVA, resulting in the formation of a fibrovascular membrane (FVM) that extends across the drainage angle, obstructing trabecular outflow and leading, initially, to open-angle glaucoma. Over time, the FVM contracts, leading to synechial angle closure and rapid onset of severe glaucoma1,6.

Clinical presentation

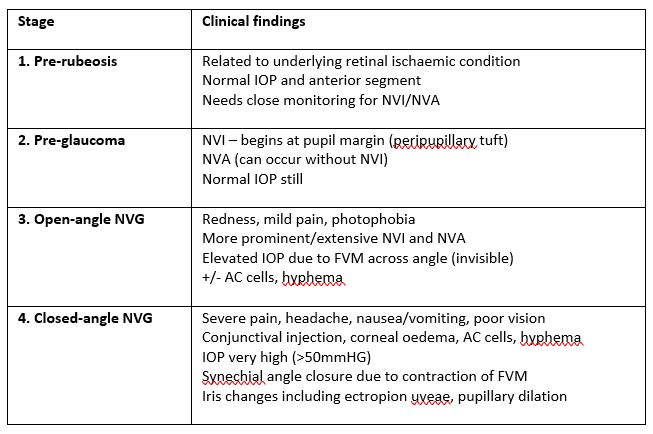

Clinical presentation depends on the stage of the disease. There are four stages that can be termed as pre-rubeosis, pre-glaucoma, open-angle glaucoma and closed angle glaucoma5. The clinical features for each are summarised in Table 2. Careful pupil margin, iris and gonioscopy assessment is needed to detect early signs of neovascularisation. NVI begins at the pupil margin as peripupillary tufts of vessels before extending across the iris. NVA characteristically appear as vascular trunks that extend from the peripheral iris to the trabecular meshwork, where they then branch for a few clock hours.

Table 2. Stages of NVG5

Management

Prevention of NVG in patients at risk (‘pre-rubeosis’ stage) is the most important aspect of management. Identifying and addressing the underlying retinal condition is essential as well as close patient monitoring for early signs of NVI/NVA. For example, following a CRVO, it is recommended patients are monitored monthly for six months.

For patients that develop anterior segment neovascularisation but without IOP elevation (‘pre-glaucoma’ stage), the mainstay of treatment is panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in combination with intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy. PRP decreases retinal ischaemia, and hence the hypoxic drive that leads to the production of angiogenic factors, and anti-VEGF agents directly block the angiogenic factors from forming new vessels. Anti-VEGF treatment often leads to the rapid resolution of neovascularisation, however PRP is more effective at preventing further recurrence.

For patients that present acutely with high IOP (‘open-angle’ or ‘closed-angle’ stages), immediate IOP reduction is needed to prevent vision loss and to relieve pain. Patients are treated with oral or intravenous acetazolamide in addition to topical treatment, including beta-blockers (eg. timolol), alpha-agonists (eg. brimonidine) and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (eg. Azopt). Prostaglandin analogues and pilocarpine tend to be avoided as they can increase inflammation. Topical corticosteroids are used to settle inflammation and atropine to provide cycloplegia. Intravitreal Avastin is given once IOP has normalised (in combination with an AC paracentesis to prevent an IOP spike) and PRP performed as soon as possible.

Many patients will subsequently need glaucoma surgery to control IOP. For eyes with visual potential, insertion of a glaucoma drainage device (eg. Baerveldt or Molteno tube) is considered the first-line option as this has a better success rate compared to trabeculectomy in NVG3. For eyes with no visual potential, the primary aim of treatment is comfort and this can usually be achieved with medical management. However, cyclo-destructive procedures like cyclodiode laser can be considered if medical treatment is insufficient.

Prognosis

For patients that are diagnosed early and promptly treated, useful vision may still be retained. However, the majority of patients do end up with poor vision due to a combination of the underlying retinal ischaemia and glaucomatous optic neuropathy, as well as other secondary complications like CMO, cataract and corneal decompensation. Furthermore, NVG is also associated with a high mortality rate of approximately 20%, indicating these patients likely have severe systemic vascular disease as well5.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Richard Johnson from Greenlane Clinical Centre for providing the case report details.

References

- Aref AA. Current management of glaucoma and vascular occlusive disease. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2016; 27:140-145

- Brown GC, Magargal LE, Schachat A et al. Neovascular glaucoma. Etiologic considerations. Ophthalmology 1984; 91:315-320

- Rodrigues GB, Abe RY, Zangalli C et al. Neovascular glaucoma: a review. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous 2016.

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman BM. Ocular neovascularisation associated with central and hemi-retinal vein occlusion. Retina 2012; 32(8):1553-1565

- Shazly TA, Latina MA. Neovascular Glaucoma: Etiology, Diagnosis and Prognosis. Seminars in Ophthalmology 2009; 24(2):113-21

- Ehlken C, Grundel B, Michels D, et al. Increased expression of angiogenic and inflammatory proteins in the vitreous of patients with ischaemic central retinal vein occlusion. PLoS One 2015.

Dr Hussain Patel is a consultant ophthalmologist at Greenlane Clinical Centre specialising in glaucoma and cataract surgery. He is also a senior lecturer in ophthalmology at the University of Auckland and works in private practice at Eye Surgery Associates.