Global call for action on preventable blindness

A new report commissioned by The Lancet Global Health, co-authored by Associate Professor Jacqueline Ramke from the School of Optometry and Vision Science at Auckland University, highlights the worldwide prevalence and causes of blindness and vision impairment, and calls on governments to act to improve eye health for all.

The report found 90% of vision loss worldwide (771 million people) is preventable or treatable, with 161 million people suffering from uncorrected refractive errors, 100 million people with cataract, and 510 million people with near-vision impairment. The report also found 77 million people with vision loss (10%) require ongoing management and treatment for conditions such as age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy.

“It is unacceptable that more than a billion people worldwide are needlessly living with treatable vision impairment,” said report co-chair Professor Matthew Burton, director of the International Centre for Eye Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). “Vision impairment leads to detrimental effects for health, wellbeing and economic development, including reduced education and employment opportunities, social isolation and shorter life expectancy. As the Covid-19 pandemic brings renewed emphasis on building resilient and responsive health systems, eye health must take its rightful place within the mainstream health agenda and global development.”

Prof Matthew Burton

Looking at the distribution of vision loss, in 2020 rates of blindness were up to nine times higher in western sub-Saharan Africa (with 1.11% of adults affected) than in high-income North America (0.12%). Most people who are blind or have moderate to severe vision loss live in South Asia (108 million), east Asia (63 million) and southeast Asia (35 million).

“The report reveals a deep inequity. There are differences in the ways different population groups are affected by vision loss,” said A/Prof Ramke, who’s also associate professor of Global Eye Health at the International Centre for Eye Health at LSHTM. “The vast majority of people impacted by vision loss (90%) reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), but in all countries there are groups unable to access the eye care they need. Impaired vision disproportionately affects women, rural populations and ethnic minority groups, with estimates suggesting that for every 100 men living with blindness or moderate to severe vision loss there are 108 and 112 women affected, respectively, often due to reduced access to care.”

A/Prof Jacqueline Ramke

Another major barrier to eye care in LMICs identified by the report is the shortfall of eye healthcare workers, with one ophthalmologist serving one million people in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, compared with an average of 76 ophthalmologists per million people in high-income countries. The scale of the challenge leads to a large economic cost globally, said A/Prof Ramke, with analysis indicating that the cost of blindness and moderate to severe vision loss globally in terms of lost productivity was US$411 billion in 2020. “As part of the commission, we identified clear evidence that improving eye health contributes to several of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals*, including reducing poverty, inequality and improving education and access to work.”

The commission’s report highlights that without additional investment in global eye health, 1.8 billion people will be living with untreated vision loss by 2050, with the vast majority (90%) residing in LMICs, the greatest proportion in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

A local perspective

Invited to comment on the report by The Lancet, Dr Matire Harwood, Associate Professor with the department of general practice and primary care at Auckland University, and Auckland-based ophthalmologist Dr Will Cunningham wrote they were pessimistically optimistic, stressing it was crucial to act and build on this work to address inequities. “Eye healthcare and research, which is people-centred, Indigenous-led, tackles the intergenerational wider determinants and has a culturally safe workforce will not only achieve equity but also has the potential to benefit all, contribute to the global sustainable developmental goals and, as Fred Hollows aspired, make the world a better place.”

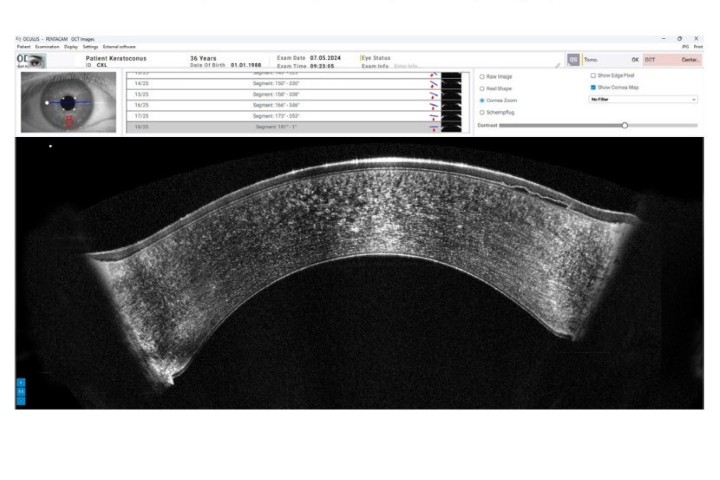

Recognising New Zealand as an outstanding example of Covid-19 management, the pair emphasised Aotearoa still experiences eye health inequities. “Indigenous people, including Māori and Pasifika, have higher rates of uncorrected refractive error, keratoconus, untreated cataract and diabetic retinopathy. Aotearoa is also afflicted by universal eye health issues, including the absence of Indigenous workforce representation, complex barriers to healthcare and scarce research that specifically examines equitable eye care.”

A/Prof Harwood and Dr Cunningham concluded their invited commentary with a Māori proverb about optimism, courage and passion – “Whāia te iti kahurangi, ki te tūohu koe me he maunga teitei” (Pursue that which is precious and do not be deterred by anything less than a lofty mountain) – and commended the report’s authors for their “sustained optimism to scale the imposing inequities and political inertia, the courage to seek transformative change, and the love they have for people who deserve better. We challenge the courageous, the loving, and the pessimistic optimists to join them.”

*The UN requires all member states to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs) under the ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, described as "a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future". In total, there are 17 SDGs, including no poverty; zero hunger; good health and wellbeing; quality education; gender equality; clean water and sanitation.

Improving vision beyond 2020

Building on the foundation laid by World Health Organisation (WHO) and its Vision 2020 partners and the recent WHO World Report on Vision, The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health report calls on governments to develop and deliver comprehensive eye health services that are well-integrated in national health systems, are people-centred and further the UN’s sustainable development goals.*

- Adopt a new definition of eye health, including maximised vision, ocular health and functional ability, recognising its contribution to overall health, wellbeing, social inclusion and quality of life

- Promote the rights of people with vision impairment by creating a more inclusive society, for example by providing rehabilitation services, assistive technology, and accessible spaces

- Include eye health as a key component of universal health coverage, as part of the planning, resourcing and delivery of wider healthcare, including strengthening eyecare primary care

- Eliminate cost barriers to eyecare by incorporating population needs into national health financing to pool risk and protect the most vulnerable

- Improve access to quality eyecare, particularly in remote areas, using technology and treatment developments in telemedicine, mobile health and AI

- Expand the eye health workforce to meet population needs, for example by increasing the number of skilled personnel, strengthening training and providing better equipment

- Integrate eye health teams into the general health workforce and train general healthcare workers in eye health

The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health is the work of an interdisciplinary group of 73 academics and national programme leaders and practitioners from 25 countries.

For more, see https://globaleyehealthcommission.org/ and https://www.iapb.org/learn/vision-atlas/, the latter offering a graphic illustration of some of the findings included in the report.